One of the important supporting characters in a new novel I expect to publish in the fall is a Black veteran of World War I. He got me to wondering how much, or how little, most of us know about the military service of African-Americans over time, especially prior to World War II. Or about how they were treated afterward.

As I did research for the novel, I discovered that even though I had studied history in college and graduate school, there was much that I had forgotten. Especially regarding numbers.

Numbers (mostly rounded here) are only part of the story, but they tell us a lot. African Americans have served in the U.S. military since colonial times. Roughly 6,000 Blacks served as soldiers in the Revolutionary War. Far fewer served during the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. But more than 200,000 served the Union in the American Civil War of 1861-65. Thirty thousand of those were in the navy. Most of the rest made up 135 different infantry regiments. Following the Civil War and up to the end of the nineteenth century, 12,500 African Americans and Seminole-Negro Indians served as scouts in the army.

Numbers (mostly rounded here) are only part of the story, but they tell us a lot. African Americans have served in the U.S. military since colonial times. Roughly 6,000 Blacks served as soldiers in the Revolutionary War. Far fewer served during the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. But more than 200,000 served the Union in the American Civil War of 1861-65. Thirty thousand of those were in the navy. Most of the rest made up 135 different infantry regiments. Following the Civil War and up to the end of the nineteenth century, 12,500 African Americans and Seminole-Negro Indians served as scouts in the army.

Particularly during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, most Black soldiers fought hoping for freedom and a better life. The Civil War ended slavery but not discrimination, despite the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. African Americans were free of slavery but not free of ill treatment based on the color of their skin.

In what came to be known as the Consolidated Civil Rights Cases of 1883, the Supreme Court merged five separate cases and struck down provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 that had prohibited informal segregation of public accommodations such as restaurants, hotels, theaters, and railroads.

That cleared the way for a plethora of state and local laws, known collectively as “Black Codes,” or “Jim Crow Laws,” across the South and elsewhere providing for formal segregation of public facilities. In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of these laws in Plessy v. Ferguson, a case arising from an attempt by Homer Plessy, a Black man, to ride a Whites-only rail car in Louisiana.

Between emancipation and 1896, there also came the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camelia, and widespread vigilante lynchings of Blacks. African-American journalist Ida B. Wells documented 3,182 such killings between 1882 and 1909. And they did not stop then.

One other thing important to remember when looking back at African-American service in WWI is Southern Black migration to the North. In 1914 there were approximately 10 million Blacks in the United States, and 90 percent lived in the South. Between 1915 and 1919, more than 500,000 migrated to northern cities in search of better jobs and a better life.

Competition for work, chiefly though not alone, led to a number of deadly race riots during that period. One of the deadliest occurred in East St. Louis, Illinois, where in 1917, an estimated 40 to 250 African Americans were killed and 6,000 left homeless.

As WWI approached, Blacks were divided about serving in the army. Many saw it as a way to demonstrate that they deserved equal rights of citizenship, and hopefully gain them. W.E.B. Du Bois, founder of The Crisis and the National Association for Colored People, called upon Blacks to serve and prove themselves. Others, like Black socialist leaders A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen, founders of The Messenger, urged Blacks to avoid military service and concentrate instead on the struggle at home for integration and labor union representation.

As WWI approached, Blacks were divided about serving in the army. Many saw it as a way to demonstrate that they deserved equal rights of citizenship, and hopefully gain them. W.E.B. Du Bois, founder of The Crisis and the National Association for Colored People, called upon Blacks to serve and prove themselves. Others, like Black socialist leaders A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen, founders of The Messenger, urged Blacks to avoid military service and concentrate instead on the struggle at home for integration and labor union representation.

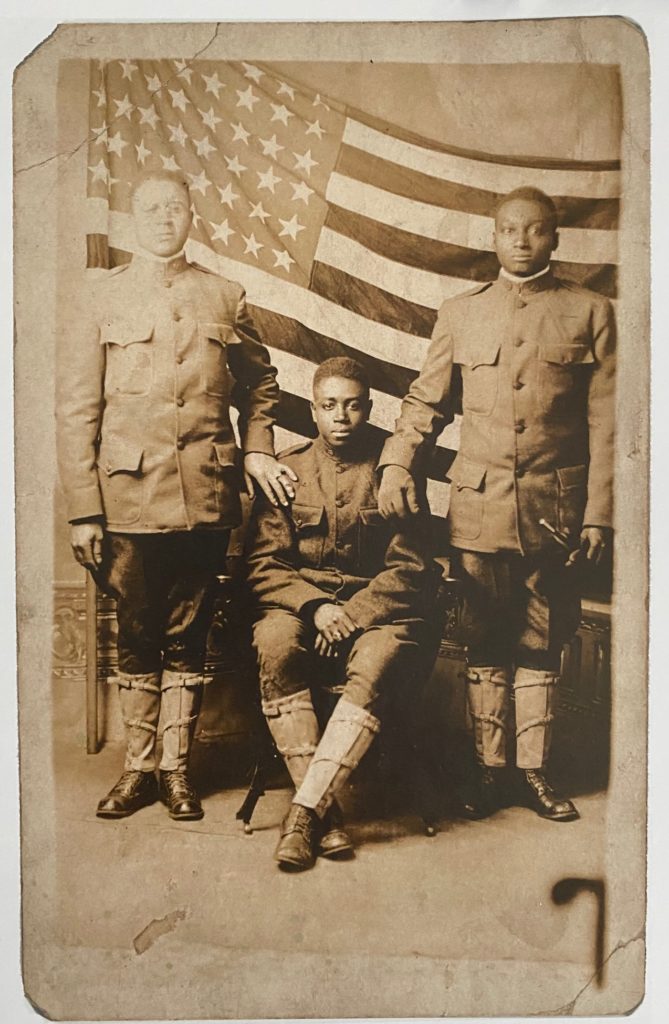

Then came the draft. Despite President Woodrow Wilson’s having segregated all government service in 1913, the Selective Service Act of 1917 required all men, regardless of race, between 21 and 31 to register for the draft. The following year the age range was extended to 18 to 45. Across the country, 155 district boards and 4,648 local boards determined who was drafted and who was not.

During those two years, 1917 and 1918, these boards collectively certified for the draft 32 percent of Whites they examined and 51 percent of Blacks they examined. One-fourth of all certified Whites were drafted; one-third of all certified African-Americans were drafted. Disparity and discrimination are obvious in the numbers.

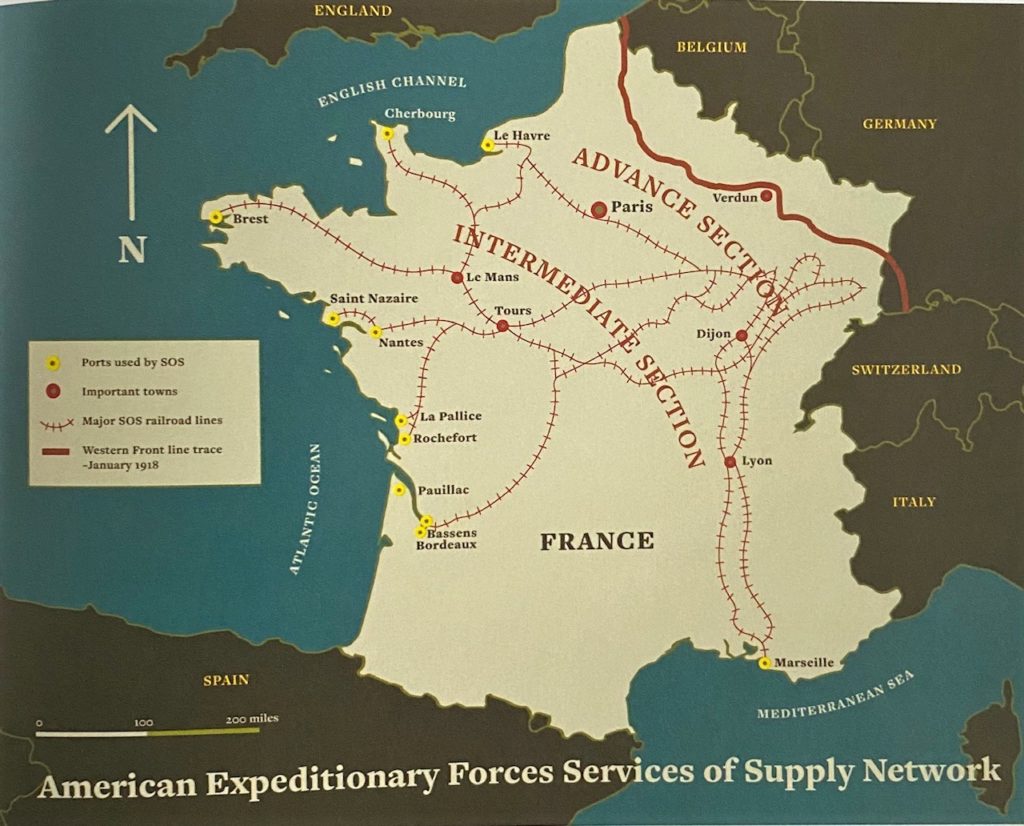

Altogether, 400,000 African Americans served in the U.S. military during WWI. Thirty thousand of those were volunteers; the rest were draftees. Half of the 400,000 served overseas. Of those, 160,000 served in SOS (Service of Supply) units because of White leadership’s hesitancy about training Blacks for combat.

The SOS units provided the lifeblood of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France, unloading supplies at major ports such as Bordeaux, Brest, and Nantes, and serving throughout the country at Lyon, Château-Thierry, Le Mans, and other locations. One White observer of their work said, “They packed and unpacked the American Expeditionary Forces in a manner never attempted since Noah loaded the Ark.”

The SOS units provided the lifeblood of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France, unloading supplies at major ports such as Bordeaux, Brest, and Nantes, and serving throughout the country at Lyon, Château-Thierry, Le Mans, and other locations. One White observer of their work said, “They packed and unpacked the American Expeditionary Forces in a manner never attempted since Noah loaded the Ark.”

Black SOS units were also instrumental in locating, retrieving, and burying the dead bodies of American soldiers following major engagements. Many Black soldiers remained in Europe after the war to finish the task.

There were two all-Black infantry divisions in the AEF—all-Black that is, except for officers, almost all of whom were White. The 92nd Infantry Division (Provisional) consisted of three African-American National Guard units. All were volunteers. The 93d Infantry Division was made up of the 365th, 366th, 367th, and 368th Regiments of draftees.

The 93d Infantry saw action in Campagne, Thur, Vosges, Verdun, and the Argonne Forest, but the 369th Division of the 92d Infantry was the most highly celebrated Black unit. Formerly the 15th New York National Guard, it became known during the war as the “Harlem Hellfighters.”

AEF Commander, General John J. Pershing, did not want America’s Black soldiers integrated into U.S. units. And in March 1918, when he assigned the 369th to fight alongside the French 16th Division, he warned the French not to treat the Black soldiers as equals. Doing so, he said, would cause social problems in the U.S. when they returned home.

AEF Commander, General John J. Pershing, did not want America’s Black soldiers integrated into U.S. units. And in March 1918, when he assigned the 369th to fight alongside the French 16th Division, he warned the French not to treat the Black soldiers as equals. Doing so, he said, would cause social problems in the U.S. when they returned home.

The French ignored Pershing’s admonition, however, and the 369th enjoyed a level of respect they had never experienced in America. They also helped hold back constant German assaults for a month. Moved subsequently to Minacourt, the unit helped the French 161st Infantry drive back German units during the Second Battle of the Marne.

In total, the 369th spent 191 days in battlefield trenches, more than any other American regiment. Its members earned the French Croix de Guerre, awarded for heroic deeds in combat. Several received U.S. Distinguished Service Crosses, and one—Henry Johnson of Albany, New York—received the U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor, though it was not awarded until 1991.

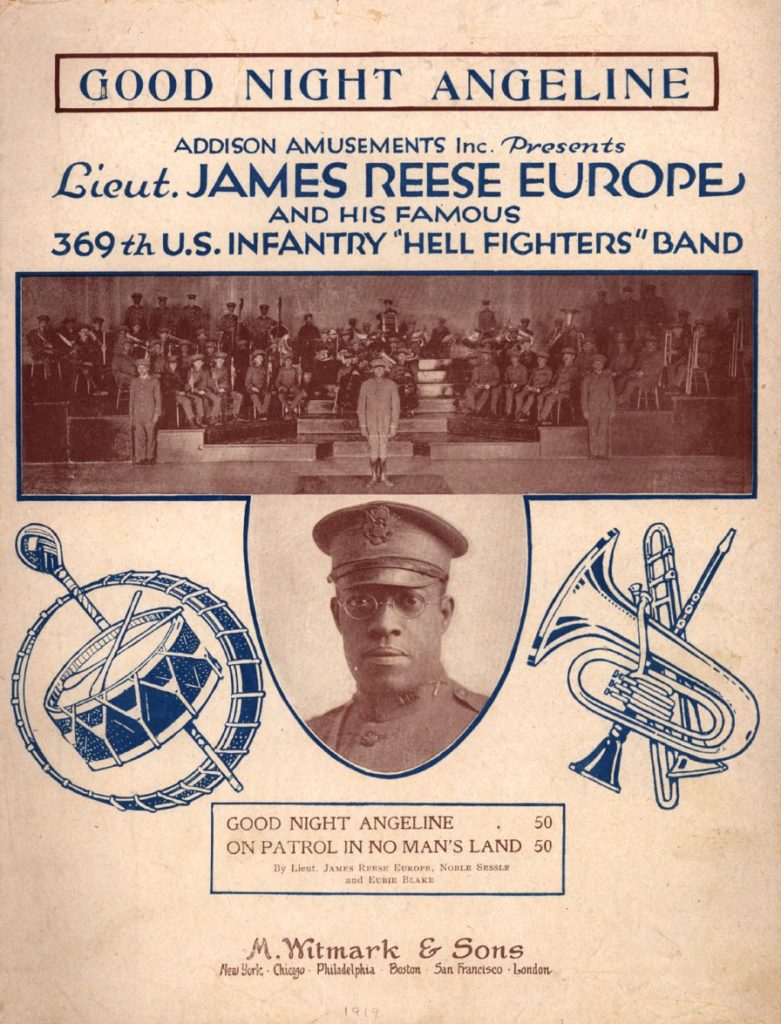

The Hellfighters weren’t known for military prowess alone. The 369th’s regimental band became one of the most famous musical units of the war, helping introduce European audiences to jazz. The band’s leader, James Reese Europe, a well-known Broadway performer, enlisted for combat. But the regiment’s white commander, Colonel William Hayward, persuaded him to form a regimental band and allowed him to recruit Black musicians from across the country.

The Hellfighters weren’t known for military prowess alone. The 369th’s regimental band became one of the most famous musical units of the war, helping introduce European audiences to jazz. The band’s leader, James Reese Europe, a well-known Broadway performer, enlisted for combat. But the regiment’s white commander, Colonel William Hayward, persuaded him to form a regimental band and allowed him to recruit Black musicians from across the country.

Despite their stellar performance and general acceptance by the French people, African-American troops were excluded from the massive Allied Victory Parade in Paris on July 14, 1919, Bastille Day. Some returned home to victory parades in Black sections of New York and Chicago, but those were anomalies.

Whatever hopes Black soldiers might have had for gaining full rights of citizenship after the war evaporated quickly. Recognition that the Black troops were battle-hardened veterans and no longer stereotyped “boys” struck fear in the hearts of prejudiced White media and leaders.

Whatever hopes Black soldiers might have had for gaining full rights of citizenship after the war evaporated quickly. Recognition that the Black troops were battle-hardened veterans and no longer stereotyped “boys” struck fear in the hearts of prejudiced White media and leaders.

Racist rhetoric was rampant, and deadly. For example, after Senator James K. Vardaman of Mississippi said Whites ought to greet “French women-ruined Negro soldiers” with violence, at least a dozen Black soldiers in uniform were lynched.

That kind of racial bigotry combined with hundreds of thousands of newly discharged job-seeking White and Black soldiers and other major currents of the time—such as reduction in wartime manufacturing, poor working conditions in industries like steel making and coal mining, rampant inflation, union organizing, and concern about socialism and foreign “outsiders”—to create a powder keg of social unrest.

The slightest incidents between races touched off large-scale violence. Overall, the summer of 1919 became known as “Red Summer,” as White mobs invaded Black neighborhoods and attacked Black veterans in more than 50 cities across the country.

The slightest incidents between races touched off large-scale violence. Overall, the summer of 1919 became known as “Red Summer,” as White mobs invaded Black neighborhoods and attacked Black veterans in more than 50 cities across the country.

Much about the way African Americans responded in 1919 and immediately after helped set a tone for their continued pursuit of equality. Variously led and inspired by Black veterans, they organized for self-defense, demanded their civil rights through the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and an increasingly vibrant Black press, and pressed for justice in American courts.

As we all know, violence against African Americans did not end in 1919. Nor the year after that, nor the decade after that, nor even a century later. There has been much progress in the quest for equality and justice, but those goals remain only partly realized.

We cannot change the past, but there is much we can do to increase our knowledge and understanding of it, and to use that information to help change the present and the future. One of those things is to take time during Black History Month to look back on and appreciate the sacrifice and service of Black soldiers during World War I.

No mere blog can do justice to the story of Black soldiers in WWI and after. See this documentary film on YouTube for a more thorough overview. If the link does not work, search Google Harlem Hellfighters’ Great War Full Movie.

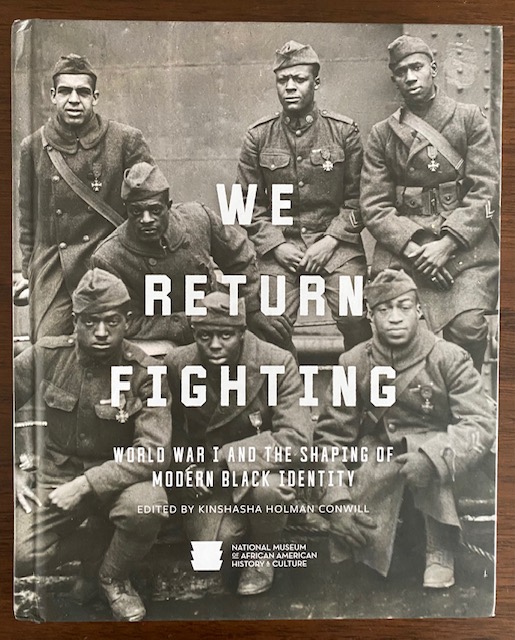

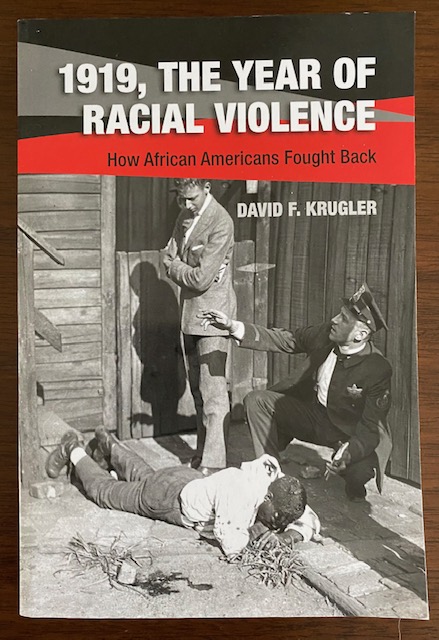

Most background information and images for this blog are from Kinshasha Holman Conwill, editor, We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, published in 2019 by Smithsonian Books in association with an exhibit of that same title at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Additional background is from David F. Krugler, 1919, the Year of Violence: How African Americans Fought Back, published in 1915 by Cambridge University Press. The painting is by French artist Raymond Desvarreux.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.