Actually, there was only one of each. But that was enough to sandwich me between two U.S. Navy petty officers and dangle me in the air over the New Mexico desert during the Nixon administration.

I’ll get to the sandwich, the dangle, and Nixon in a moment. First, a little context.

In 1935, Congress passed the Historic Sites Act creating a National Register of places important in state and local history. The National Park Service (NPS) oversaw the register, but states proposed the sites. In 1966, the National Historic Preservation Act added new requirements about preserving those places and created a National Historic Landmarks (NHL) program to find sites that had national significance. That’s where this story started for me.

The NHL program proved popular, and in the early 70’s, the NPS contracted with the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) to help with it. The AASLH hired me to manage that task, and eventually we added three other historians.

To gather comparative data necessary to determine which potential landmarks were nationally important and which were not, the NPS studied them thematically. Working out of AASLH headquarters in Nashville, TN, our contract team drew “Political and Military Affairs from 1865 to 1900” as our first project.

To find additional NHLs, we had to study the political and military history of each state, determine if any previously recorded state and local sites merited elevation to national status, and examine all sorts of other sources for sites the states might have overlooked.

Many important national historic sites are situated on military bases and other federal properties. And when a building or district on one of those is designated a NHL, the administrator responsible for that property has to preserve it without the benefit of any additional funding. Naturally, this often causes push back. That’s what led to the elbows in my ribs.

Every couple of months, one of us would travel for two weeks or so making prearranged visits to potential NHLs at the rate of one or two each day—to eyeball them, gather additional information about them, photograph them, and chart their exact locations on U.S. Geological Survey maps.

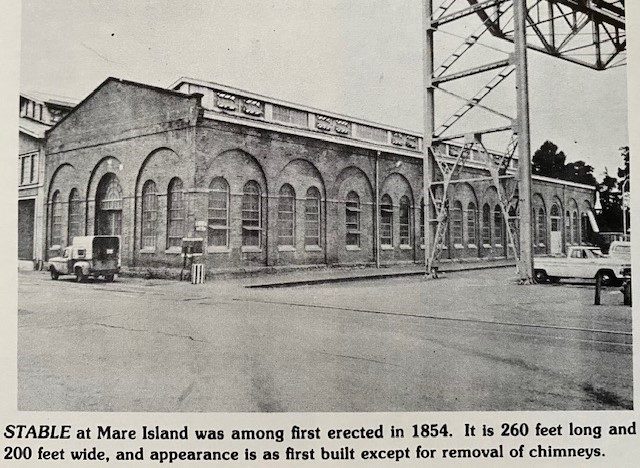

One of the sites on my list was the Mare Island Naval Shipyard on the Napa River, which flows southward into San Francisco Bay. It was the first U.S. naval base on the Pacific coast, the navy’s primary Pacific coaling station in the steam era, and an important WWII ship repair facility. Many of the early machine shops, storage, and other buildings were still standing and seemed in good condition. But now it was the premier West coast home for nuclear submarines, with a lot of top secret stuff all around.

One of the sites on my list was the Mare Island Naval Shipyard on the Napa River, which flows southward into San Francisco Bay. It was the first U.S. naval base on the Pacific coast, the navy’s primary Pacific coaling station in the steam era, and an important WWII ship repair facility. Many of the early machine shops, storage, and other buildings were still standing and seemed in good condition. But now it was the premier West coast home for nuclear submarines, with a lot of top secret stuff all around.

Following protocol, I phoned ahead and set up a time to visit. A couple of days before I was scheduled to leave Nashville, however, an adjutant in the base commander’s office called to say that most of the things I wanted to see were in classified areas and I was no longer welcome. I phoned my NPS contact in Washington with this news, and he instructed me simply to call the adjutant back and inform him that under Presidential Executive Order (EO) 11593, they could not stop me from coming.

This is where President Nixon comes in. A few years earlier, in 1971, he had issued EO 11593 directing that all federal property administrators cooperate with the Park Service, which meant, among other things, allowing its researchers access to any area they wanted to see. By extension, the order also applied to its contractors. I called the navy guy back, we talked, and after he conferred with his boss, he told me, “All right, come on.” I was really pleased with myself—till I got there.

When I arrived, I asked for and got maps confirming building dates and showing precise locations. However, a junior officer confiscated my camera and said they would send me whatever photographs they wanted me to have. He then thrust me into the back seat of a Shore Patrol car with a burly non-commissioned officer seated on each side of me.

As their elbows pressed into my sides, the driver sat up front with an officer who told me to indicate which of the magnificent red brick, industrial-type, waterfront buildings I wanted to see. He said they would drive me to them, but I couldn’t get out of the car to look at them. “It’s okay to make notes,” one of them said. I started to ask how, inasmuch as I couldn’t move my arms, I was supposed to do that. But I knew it wouldn’t do any good, and I settled for making cryptic scribbles.

Not long into our car tour, I noticed fishermen in rowboats on the other side of the river and wished I had brought a casting rod. I was probably wrong, but at that moment the navy didn’t seem to me to be as concerned about guys with fishing poles in boats and possibly telescopic lenses under their seats as they were about historians walking around with notebooks.

I also used EO 11593 to get onto Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, TX. But once I cited it to the authorities there, they became pretty nonchalant about the whole matter—that is, all but one of them. I was given permission to walk almost anywhere I wanted and take all the photographs I wanted.

Unfortunately, no one told the base commander. I was especially interested in Officer’s Row, a long array of impressive, late-19th-century, multi-storied, brick officers’ houses in near-pristine shape, and I strolled up the walkway of the largest one to get a closeup of the millwork on the sweeping veranda. Just as I raised my camera, a large man dressed in PJ’s and a striped bathrobe stepped out of the front door and stooped to pick up a folded newspaper. Upon rising, the first thing he saw was my camera pointed directly at him. All I remember noticing after that was how red in the face he turned. That and the huge cigar he jerked out of his mouth.

Unfortunately, no one told the base commander. I was especially interested in Officer’s Row, a long array of impressive, late-19th-century, multi-storied, brick officers’ houses in near-pristine shape, and I strolled up the walkway of the largest one to get a closeup of the millwork on the sweeping veranda. Just as I raised my camera, a large man dressed in PJ’s and a striped bathrobe stepped out of the front door and stooped to pick up a folded newspaper. Upon rising, the first thing he saw was my camera pointed directly at him. All I remember noticing after that was how red in the face he turned. That and the huge cigar he jerked out of his mouth.

“Who the hell are you?” he yelled. “What are you doing there?” I don’t know who was startled most, me or him. After I gathered myself and explained, he stared at me for what seemed like a long time then said something like, “Goddamn it, why didn’t anybody tell me?” I had no answer for that, so he stuffed the cigar back between his teeth and went inside, leaving me standing there surprised that he hadn’t told me to get the hell away despite the executive order.

Over nearly two years on that project, I visited a number of other military installations, mostly army bases and abandoned forts. And I found that the navy struggled more with the process than the army. When I checked in at the Washington Navy Yard in the District of Columbia, like at Fort Sam Houston, they told me I could walk around and take all the photos I wanted. Having learned a lesson, however, I suggested that they give me some sort of written pass in case I was stopped by someone. “You won’t need it,” the officer meeting with me said. Later in the day, after the second time a member of the Shore Patrol picked me up and hauled me back to the main gate in a jeep for questioning, someone decided that a pass would be a good idea. And sure enough, I was stopped again later on. No jeep trip that time, though.

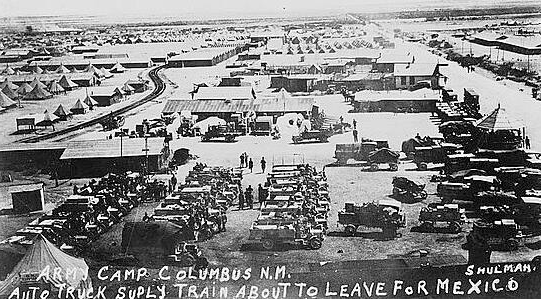

The greatest outliers in our whole study of military sites, however, were the senator and the motorcycle. They had nothing to do with EO 11593, but the senator was an at-least-equal point of authority. Not long before I was to leave on another long swing out West, I received a call from the NPS directing me to include Columbus, NM, the site of Pancho Villa’s infamous 1916 raid across the U.S. border and staging area for General Pershing’s pursuit of him. “I can’t,” I said, “that’s outside the timeframe of our theme.”

The greatest outliers in our whole study of military sites, however, were the senator and the motorcycle. They had nothing to do with EO 11593, but the senator was an at-least-equal point of authority. Not long before I was to leave on another long swing out West, I received a call from the NPS directing me to include Columbus, NM, the site of Pancho Villa’s infamous 1916 raid across the U.S. border and staging area for General Pershing’s pursuit of him. “I can’t,” I said, “that’s outside the timeframe of our theme.”

“Oh, yes, you can,” the parks executive said. “Senator Montoya wants it included.” Joseph Montoya, late of the Senate committee that conducted the Watergate hearings prior to President Nixon’s resignation, was accustomed to getting what he wanted. And he did again this time.

I adjusted my schedule and headed to Columbus, which by then was only a sparsely populated artists’ colony. Once there I met up with an official from the New Mexico state historic preservation office, toured around, and took some pictures. The official then drove me outside of town to the sprawling retirement home of a state preservation activist and amateur historian so I could explain the NPS process to him and some other community leaders and ask them about some of the old buildings.

As we sat in our host’s expansive family room, he pointed to my camera bag on the floor beside my chair and asked if I ever took aerial photographs. I explained that, no, I wasn’t tasked to do that. He said, “Seems like it’d be a good idea. Grab your bag and come on.” Too surprised to refuse, I did as he asked. He led me down a long hallway, through a gigantic kitchen, and into a huge garage, where I saw a four-seater prop airplane parked alongside a pickup and several cars. A big ole Harley was strapped in behind the plane’s rear seats. While I was trying to figure out how the fellow got the motorcycle in and out of there, he said, “Get in the back.”

Fearing that if I refused he might not give me the rest of the information I still needed about the old buildings, I tried to strike a nonchalant manner and climbed in while hoping he didn’t notice how low my jaw had dropped and my knees were knocking. He cranked the engine and taxied out of the garage onto a landing strip adjoining his backyard in the desert. The next thing I knew, he was banking steeply over the little town while I snapped photographs and hoped that the damned motorcycle, which was creaking against its restraints, didn’t come loose and push me out of the side window he had insisted I open so I could get clearer shots.

Fearing that if I refused he might not give me the rest of the information I still needed about the old buildings, I tried to strike a nonchalant manner and climbed in while hoping he didn’t notice how low my jaw had dropped and my knees were knocking. He cranked the engine and taxied out of the garage onto a landing strip adjoining his backyard in the desert. The next thing I knew, he was banking steeply over the little town while I snapped photographs and hoped that the damned motorcycle, which was creaking against its restraints, didn’t come loose and push me out of the side window he had insisted I open so I could get clearer shots.

When we were safely back on terra firma, he explained that occasionally he took classes at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. He would fly into the airport there and ride his motorcycle to campus. I started to tell him that when I’d been there recently doing research on Fort Selden, a Vietnam War-protest bomb scare had prompted evacuation of the library. But I didn’t. It wasn’t going to impress someone nuts enough to do photo dives over the desert in a single-engine airplane with a huge motorcycle straining its harness behind him.

At least I had managed not to fall out of the plane. And in time, portions of all the aforementioned sites except Fort Selden were accorded National Historic Landmark status. To this day, though, nearly every time I hear about presidential executive orders or watch a U.S. Senator demanding something or other on TV, the number 11593 echoes verbally through my mind—“eleven five ninety-three, eleven five ninety-three, eleven five ninety-three….” And the visual that comes with it is not a title on a piece of paper in a sharp, dark blue binder. It’s “11593” on a New Mexico motorcycle license plate.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.