Other than I sometimes spend a few moments looking for four-leaf clovers while I’m outside with my dog Gracie, this post has nothing to do with clover. It has a lot to do, though, with luck and a particular scenic rock.

Other than I sometimes spend a few moments looking for four-leaf clovers while I’m outside with my dog Gracie, this post has nothing to do with clover. It has a lot to do, though, with luck and a particular scenic rock.

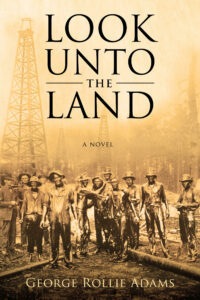

And that rock has a lot to do with my latest novel, Look Unto the Land, which will be out shortly and which this blog gives me an excuse to call attention to. I know I ended that sentence with a preposition, but authors of novels have considerable latitude to break grammatical rules. At least that’s what I say when I’m questioned about bending one.

But I digress. Truth is, I don’t really know if the rock in question was scenic. It was life-changing, though, and the view from it across the Canadian Rockies must have been near postcard perfect. In the fall of 1973, it stopped a whole busload of public historians and museum professionals. They piled off the coach to gawk, then set out hiking to explore all the vistas the overlook provided.

This was right after a meeting of the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) in Edmonton, the oil-rich capital of Alberta Province in Canada. Two of the post-meeting tourists returned to the coach before the others, and instead of climbing back aboard, they sat down on a huge boulder-like rock to rest and continue enjoying the view. While sitting there, they did more than look. They conspired to set me on a path to a new future.

At the time, I was finishing up my doctoral work in American history at the University of Arizona, and even though I was still working on my dissertation and would not receive my degree until a few years later, I was looking for a job. Despite having grown up in oil-rich southern Arkansas, I wasn’t interested in oil history and certainly never expected that someday I would write about it, even in a fictionalized account. But for that rock in oil-rich Alberta, I probably never would have.

One of the people who sat down on the rock was the director of educational programs for the AASLH, headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. The other was the editor of the Colorado Magazine (now Colorado Heritage), published by the State Historical Society of Colorado (now known as History Colorado), headquartered in Denver.

One of the people who sat down on the rock was the director of educational programs for the AASLH, headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. The other was the editor of the Colorado Magazine (now Colorado Heritage), published by the State Historical Society of Colorado (now known as History Colorado), headquartered in Denver.

As I heard later, they had apparently known each other for some time, and they chatted about a variety of things while waiting for their companions to return and board the bus. At some point near the end of the conversation, the program director said something along these lines to the editor: “I almost forgot. Bill [William T. Alderson, the AASLH director] asked me to find someone to manage a research and writing project we’re doing under contract to the National Park Service.”

She described the job to her companion. It was essentially to find and recommend previously overlooked historic sites that merited consideration for designation as National Historic Landmarks. Then she asked, “Do you know of anyone?”

She described the job to her companion. It was essentially to find and recommend previously overlooked historic sites that merited consideration for designation as National Historic Landmarks. Then she asked, “Do you know of anyone?”

The editor reportedly said something like, “As a matter of fact, I might. We were supposed to interview someone last week to be assistant editor of our magazine, but in the meantime, we found a similar candidate with a specific background in Colorado history, and we hired that person. This other fellow is in grad school in Tucson, and when I cancelled his interview, I told him I’d recommend him if something else turned up that looked like a good fit for him. If you want, I’ll send you what we have on him.”

The program director said please do, and the editor followed up. A week or so later, Bill Alderson called me from Nashville, introduced himself, told me what had happened, described the job, and asked me if I would be interested in interviewing for it.

Somehow I managed to say yes without choking on my words despite my surprise and excitement. He asked if I would meet him the following week at the annual conference of the Western Historical Society in Fort Worth, Texas. I did, and over breakfast in a huge room filled with some of the leading scholars in western US history, which happened to be my special field of study, Bill began an interview that eventually moved elsewhere and continued well into the morning.

Before lunch, he offered me the job, and after boldly negotiating for a slightly higher salary than he first offered, I accepted. I needed work so badly and the job sounded so interesting that I would have worked for less than what he initially laid on the table. I never told him that, of course.

There weren’t any four-leaf clovers in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert surrounding Tucson, but there were plenty of rocks. None, however, had the magic of that scenic rock in the Canadian Rockies. Whatever credentials I had for history work at the time seemed pale beside the good fortune it brought me without my ever laying eyes on it.

There weren’t any four-leaf clovers in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert surrounding Tucson, but there were plenty of rocks. None, however, had the magic of that scenic rock in the Canadian Rockies. Whatever credentials I had for history work at the time seemed pale beside the good fortune it brought me without my ever laying eyes on it.

Depending on one’s personal beliefs, one might argue that what happened on that rock wasn’t luck at all, but fate (whatever that is) or predestination (especially if one is Catholic or Presbyterian).

But whatever it was, it led me eventually to rewarding history jobs in Nashville, Buffalo, New Orleans, and Rochester. And most recently to my third novel, Look Unto the Land, which is centered around oil, the core of the local economy in both my home Arkansas county and the provincial economy of the province of Alberta, Canada, since the early 1900s.

A rock, two public history professionals, and luck combined to set the course of my path from high school teacher to grad student and from history museum director to novelist. And if that were not enough to make me think in hindsight that I was somehow meant to write a novel set in an oil boom in 1922, there were also two other coincidences.

A rock, two public history professionals, and luck combined to set the course of my path from high school teacher to grad student and from history museum director to novelist. And if that were not enough to make me think in hindsight that I was somehow meant to write a novel set in an oil boom in 1922, there were also two other coincidences.

The first is that while I was at the AASLH, I attended a continuing education program in museum and art gallery management at the Banff Centre, originally affiliated with the University of Alberta and now part of the University of Calgary. The second is that the chair of the search committee that brought me to Rochester in 1987 grew up in Alberta and as a young man worked as a roughneck in the Alberta oil fields.

For many years after I moved away from southern Arkansas, an aunt back there kept sending me old newspaper clippings and pamphlets about the early oil boom. I don’t recall that she ever wrote or said anything about my eventually writing something based on them. And I didn’t glum onto the idea until many years after she passed. But somehow today all these things seem part of a puzzle finally coming together. When Look Unto the Land hits the book market in the next few days, I hope it proves a worthy tribute to all the factors that led to it.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.