Pearl Goodbar, the lead character in my novel Found in Pieces, has guts. And she stands on the shoulders of giants. Readers say what they like most about her are her work ethic, her dogged determination to succeed, and her willingness to stand up for what she believes.

Pearl Goodbar, the lead character in my novel Found in Pieces, has guts. And she stands on the shoulders of giants. Readers say what they like most about her are her work ethic, her dogged determination to succeed, and her willingness to stand up for what she believes.

As I wrote in a previous blog, Pearl was a key secondary character in my first novel, South of Little Rock. Her role in that story begged for an opportunity to grow in a subsequent one. Hence, Found in Pieces. Prior to the time in which that story is set, there had been relatively few women newspaper owners, publishers, or editors in America, so I wanted to refresh what I knew about that history and learn even more. In fact, Pearl insisted on it.

Yes, novelists’ characters do come alive in the minds of their creators and speak to them. Not literally out loud, at least not in my case, but still with surprising clarity. As one thinks and writes about them, a real sense emerges as to who they are, what they think, and what they are or are not capable of. So, as I began to put words on paper—actually on screen—about Pearl, it soon became clear that I could do it better if I knew more about newspaperwomen who had come before.

I highlighted some of those in an earlier blog. Here are some others who particularly grabbed my attention.

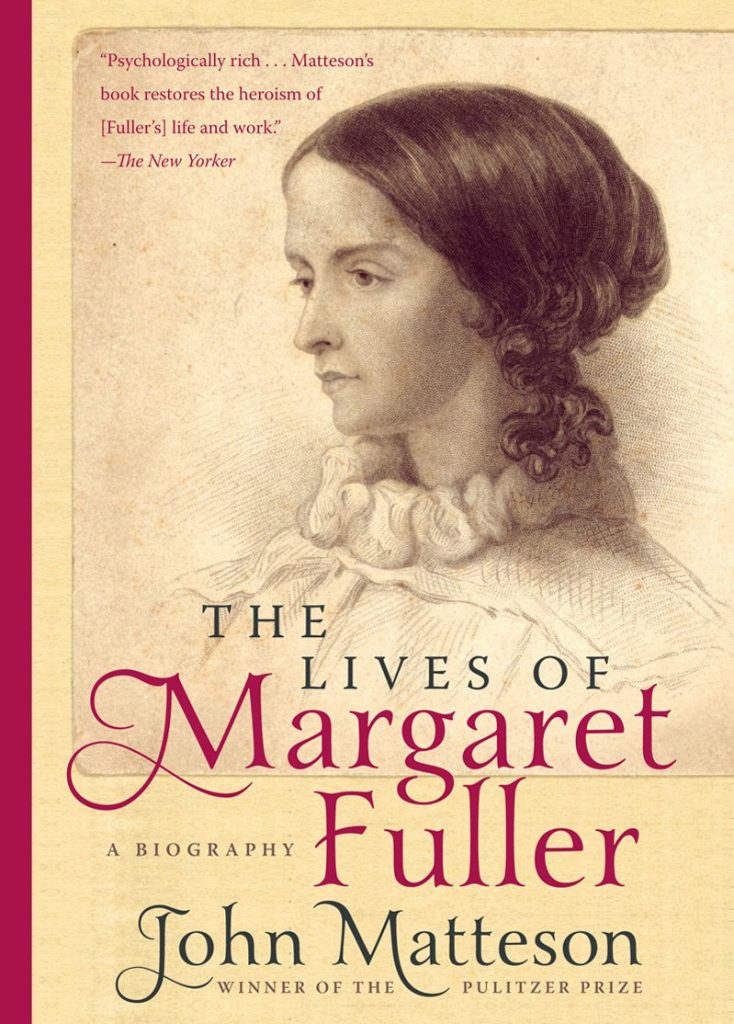

Margaret Fuller was said by Susan B. Anthony to have exerted more influence on the thought of American women than any other woman of her time. Educated by her father (a Massachusetts Congressman in the early 1800s) and at two private schools for “young ladies,” Fuller early on caught the attention of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In late 1839, he hired the widely read Fuller as editor of his transcendentalist magazine The Dial. During her stint there, she wrote two books, decried unfair treatment of Native Americans, and supported abolition, prison reform, and women’s rights.

Margaret Fuller was said by Susan B. Anthony to have exerted more influence on the thought of American women than any other woman of her time. Educated by her father (a Massachusetts Congressman in the early 1800s) and at two private schools for “young ladies,” Fuller early on caught the attention of Ralph Waldo Emerson. In late 1839, he hired the widely read Fuller as editor of his transcendentalist magazine The Dial. During her stint there, she wrote two books, decried unfair treatment of Native Americans, and supported abolition, prison reform, and women’s rights.

In 1846, Horace Greeley engaged Fuller to work at his New York Tribune as a literary critic, and later that same year, she became the paper’s first woman editor. Shortly thereafter, she traveled to Europe as America’s first foreign correspondent. While in England, she met the exiled Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini with whom she had a son. Scholars disagree about whether the couple ever married. In any case, in 1850 they set sail with the young boy for the United States. Tragically all three perished in a shipwreck less than 100 yards offshore from Fire Island, New York.

Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, once also hired by Horace Greeley to work at his New York Tribune, founded three reform-oriented newspapers in the mid-19th century. Born into a large Pittsburgh-area family ravaged by economic struggles and illness, she lost her father and 5 siblings to disease and death before she turned 16. After working for a time as a lace maker and as a village schoolteacher, despite having little schooling herself, Jane married at age 20. She and her husband lived briefly in Louisville, Kentucky, where she witnessed slavery firsthand, before settling back near Pittsburgh.

Jane Grey Cannon Swisshelm, once also hired by Horace Greeley to work at his New York Tribune, founded three reform-oriented newspapers in the mid-19th century. Born into a large Pittsburgh-area family ravaged by economic struggles and illness, she lost her father and 5 siblings to disease and death before she turned 16. After working for a time as a lace maker and as a village schoolteacher, despite having little schooling herself, Jane married at age 20. She and her husband lived briefly in Louisville, Kentucky, where she witnessed slavery firsthand, before settling back near Pittsburgh.

There in 1847, she founded the anti-slavery newspaper Saturday Visiter [sic], which also advocated for women’s property rights. It gained a national circulation before merging with a larger paper in the area. The job with Greeley’s Tribune followed, and in 1850, Swisshelm became the first female reporter allowed into a session of Congress. In 1857, she divorced her husband and moved to St. Cloud, Minnesota, where she resurrected her first newspaper as The Saint Cloud Visiter [sic] and editorialized about abolition, women’s rights, and political corruption.

In 1860, Swisshelm supported Abraham Lincoln for president, and during the Civil War, when the Union Army desperately needed nurses, she sold her paper and volunteered for service in Virginia. After the war, she founded yet another newspaper, the Reconstructionist, through which she railed against what she regarded as the shortcomings of President Andrew Johnson.

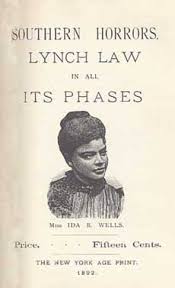

Ida B. Wells, born in 1862, emerged from an early childhood of slavery in Mississippi to become a life-long crusader for social justice. Although like Swisshelm she lost both parents at age 16, she attended Rust College and Fisk University, became a teacher, and went on to champion civil rights and women’s suffrage in the United States and abroad. She kept her maiden name when she married and raised four children despite traveling widely, campaigning energetically, and writing prolifically.

Wells began contributing free-lance newspaper articles about race and politics to various newspapers after being forced off a whites-only rail car in Tennessee in 1884. In the early 1890s, she acquired co-ownership of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper and delved especially into the scourge of lynching. By mid-decade, she had written two books about it—Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases and The Red Record—detailing her journalistic investigations.

Wells began contributing free-lance newspaper articles about race and politics to various newspapers after being forced off a whites-only rail car in Tennessee in 1884. In the early 1890s, she acquired co-ownership of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper and delved especially into the scourge of lynching. By mid-decade, she had written two books about it—Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases and The Red Record—detailing her journalistic investigations.

Over the next three decades, while living variously in New York and Chicago, Wells interacted with many of the nation’s leading activists, Black and white. During that time she founded or helped found numerous local and national civic and civil rights organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin also helped establish the NAACP. Born before Wells, in 1842, to a well-to-do interracial couple in Boston, she married George Lewis Ruffin while still in her mid-teens. He went on to become the first African-American graduate of Harvard Law School, a member of the Boston City Council, and the first Black municipal judge in the city, and the couple often worked together on social causes.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin also helped establish the NAACP. Born before Wells, in 1842, to a well-to-do interracial couple in Boston, she married George Lewis Ruffin while still in her mid-teens. He went on to become the first African-American graduate of Harvard Law School, a member of the Boston City Council, and the first Black municipal judge in the city, and the couple often worked together on social causes.

Soon after marrying, they became involved in the abolition movement, and during the Civil War, they helped recruit Black soldiers for Massachusetts volunteer regiments. After the war, Josephine organized the Freedmen’s Relief Association to help Southern Blacks exit to Kansas. She also began advocating for women’s suffrage and partnered with Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone to form the American Woman Suffrage Association.

Following the death of her husband in 1886, Ruffin launched the first newspaper published in the United States by and for African-American women. She titled it Woman’s Era and served as editor and publisher for most of the 1890s. During that same period, she organized the National Federation of Afro-American Women and helped establish the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

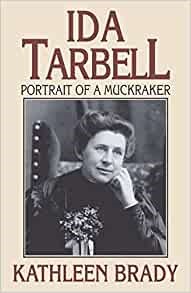

Ida Tarbell was not a newspaperwoman in the same sense as the aforementioned because she didn’t own or edit one. But she wrote for a number of newspapers and was one of the most outstanding investigative journalists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Plus, she briefly edited two different magazines—The Chautauquan in her early life and McClure’s at the turn of the century. In addition, not long after the latter job, she became part owner of The American Magazine and served for a time as its associate editor.

She is best known, however, for her muckraking exposure of the manipulative schemes that John D. Rockefeller and his Standard Oil Company used to gain a monopoly in the petroleum industry. Her disdain for Rockefeller’s tactics began when she watched them drive her oil-producing-and-refining father to near ruin in the early 1870s. In time, her series of 19 articles in McClure’s and subsequent book The History of the Standard Oil Company helped lead to dissolution of Standard Oil, creation of the Federal Trade Commission, and passage of the Clayton Anti-Trust Act.

She is best known, however, for her muckraking exposure of the manipulative schemes that John D. Rockefeller and his Standard Oil Company used to gain a monopoly in the petroleum industry. Her disdain for Rockefeller’s tactics began when she watched them drive her oil-producing-and-refining father to near ruin in the early 1870s. In time, her series of 19 articles in McClure’s and subsequent book The History of the Standard Oil Company helped lead to dissolution of Standard Oil, creation of the Federal Trade Commission, and passage of the Clayton Anti-Trust Act.

Tarbell also wrote and lectured about numerous other topics and causes, including women’s suffrage and women’s working conditions. In addition, she was a prolific biographer, producing notable volumes on Napoleon Bonaparte and Abraham Lincoln.

Like the first group of newspaperwomen that I wrote about recently, these five were extraordinary individuals whose contributions to journalism and social progress deserve our remembering and honoring them.

Although to my mind they were not pioneers to any degree approaching the other women profiled above, there are two other newspaperwomen from this era that I should at least mention. That’s because between them, there is a “Pearl” connection I confess I didn’t know about until after I wrote Found in Pieces.

Kentucky-Tennessee-border native Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer wrote her first newspaper column under the name “Dorothy Dix” and went on to international acclaim as the first syndicated advice columnist, giving counsel to millions until her death in 1951. The person who hired Gilmer to write that initial column half a century earlier was Eliza Jane Wilkerson, the first woman publisher of a major Southern newspaper.

Wilkerson inherited the New Orleans Picayune from her husband, Alva Holbrook, a man 41 years her senior, in 1876. Two years later, she married the paper’s business manager, George Nicholson. Elizabeth and Eliza met by chance in 1896, while Gilmer was visiting near where Nicholson lived, and eventually, Nicholson engaged Gilmer to produce what became the first of her thousands of “Dorothy Dix” advice pieces. When Nicholson died shortly afterward, those who mourned her passing included some who knew her by her poetry-writing pen name, “Pearl Rivers.” Sadly, however, unlike my Pearl, Nicholson was decidedly not an advocate for the civil rights of Black Americans.

I will highlight a final group of outstanding newspaperwomen in a future post.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.

Online sources for this post include: National Women’s History Museum, National Park Service, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Smithsonian Magazine, Britannica Explores, and Wikipedia.