Music does many things for us. It lifts our spirits, brings us together, inspires us, soothes us, and even eases our pain. We love to hear our favorite songs over and over, in part because they help us preserve and recall memories we treasure. I became particularly mindful of this recently while hanging a picture of my Granddaddy Wheeler Kinard and a group of his singing school students from sometime in the 1920s. (He is standing at the far left holding a baton.)

Music does many things for us. It lifts our spirits, brings us together, inspires us, soothes us, and even eases our pain. We love to hear our favorite songs over and over, in part because they help us preserve and recall memories we treasure. I became particularly mindful of this recently while hanging a picture of my Granddaddy Wheeler Kinard and a group of his singing school students from sometime in the 1920s. (He is standing at the far left holding a baton.)

I come from a musically talented family. My mother and maternal grandmother played the piano, my daddy had a good voice, and my brother was a gifted trumpet player who went on to become a high school band director for a time.

Unfortunately, I share none of their musical genes. Once in high school, when I was struggling with an alto sax passage in band, a friend half-joked, “Man, are you tone deaf or something?” I didn’t take too kindly to the remark. After all, I was first chair and had somehow managed earn a second-place medal with a quartet at that year’s state band festival.

I didn’t say anything back to him, though, because I suspected he might be right. That was chiefly because when it came to singing, I couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket—even with some Mrs. Tucker Shortening still in there for it to glum onto. (If you don’t get the Mrs. Tucker reference, you’ve never heard older folks talk about how as kids they anonymously called up people on the phone, asked if they had Mrs. Tucker in a bucket, then told them, “If you do, you better let her out.” Not that I have any first-hand experience with anything like that, mind you.)

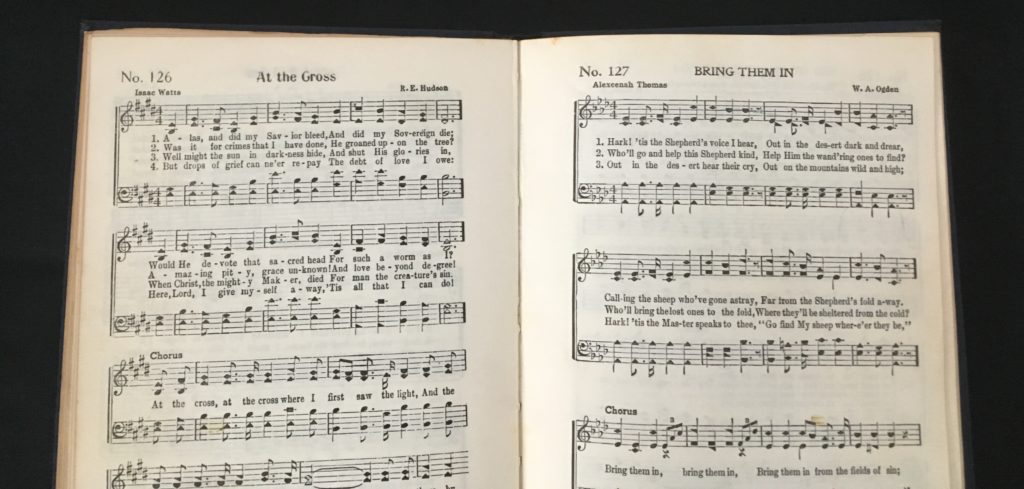

Granddaddy could carry a tune, though, and he did it across a sizeable swarth of northern Louisiana and southern Arkansas. He made his living variously as a carpenter, farmer, and merchant, but from time to time, he taught a version of shape-note gospel singing to groups of thirty to fifty children and young adults, sometimes daily for up to two weeks running. As I understand it, he would board with someone in a community and teach at a local church during the day. In the evenings others in the community would show up to listen to the students and sing along with them.

Shape-notes are a simplified form of musical notation in which the various shapes of the notes indicate pitches in major and minor scales and therefore make key signatures on the staff unnecessary. With roots in early eighteenth-century America, shape-note singing became popular all across the South during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially among Southern, Primitive, and United Baptists, Free Methodists, United Pentecostals, and Churches of Christ. Much of shape-note singing was acapella, but instrumental accompaniment, typically piano, was also common.

By the time I was growing up, shape-note singing was declining in popularity, and the church my family attended didn’t practice it. Granddaddy Kinard always insisted on using a shape-note hymnal when he sang in the choir, however. Because he sometimes sang solo or in a quartet, I can still hear him anytime I catch all or part of one of the popular old hymns of the era.

Today, a 1840s version of shape-note singing called Sacred Harp—with “harp” said to refer either to the human voice or to David the psalmist—is enjoying a wide-spread revival. I haven’t tried it, though, and I don’t think it would do much good anyway, even if I managed to find an a Mrs. Tucker Shortening bucket somewhere.

To be notified of new posts, please email me.