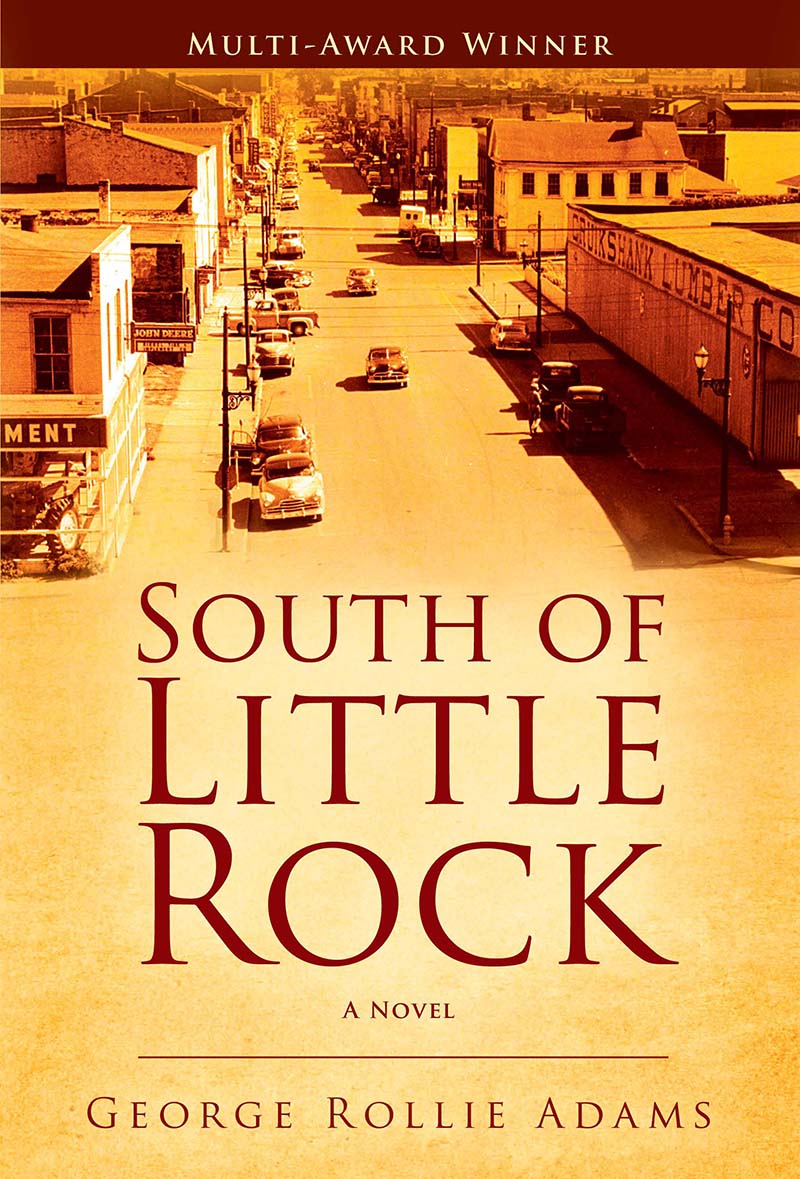

What can social movements of the past teach us about today’s socially charged climate? Within the past year, my novel South of Little Rock has received four regional and social-issue fiction awards for examining that question, and a second edition is now available. The book is a story of race, family, and the struggle of love and courage against fear and hate in a small southern town adjusting to desegregation and social change in 1957.

What can social movements of the past teach us about today’s socially charged climate? Within the past year, my novel South of Little Rock has received four regional and social-issue fiction awards for examining that question, and a second edition is now available. The book is a story of race, family, and the struggle of love and courage against fear and hate in a small southern town adjusting to desegregation and social change in 1957.

“South of Little Rock is remarkably relevant to the issues of today,” says Charles Phillips, coauthor of What Every American Should Know about American History. “Through vivid descriptions and intelligent dialogue, it explores the racial tensions of the 1950s South in a way that speaks to a modern audience.”

Set in fictional Unionville, a tiny community situated on the Arkansas-Louisiana border, the novel unfolds amid social unrest and the national crisis that Governor Orval Faubus creates when he decides to resist the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School and thereby forces President Dwight Eisenhower to send federal soldiers to enforce it. Sam Tate, a councilman, merchant, and widower tries to navigate his family through these trying times, putting him at odds with the town’s newspaper editor and other outspoken opponents of integration. Sam finds surprising allies and companions, including a hard-headed woman recently arrived from the North to teach at the elementary school. Amid the turmoil, Sam works to teach his children right and wrong in a town where the likelihood of change pits its citizens against each other and the threat of social violence looms over all of them.

Unfortunately, tensions not unlike these remain all too familiar in present-day America, as aspects of racism and bigotry with long roots linger in both old and new guises, and new fears and prejudices hold sway and grow against immigrants and others deemed by many as unworthy somehow because they are different or because they are seen as potential threats to the status quo.

When I was writing South of Little Rock, I knew that new novels focusing on race appear frequently, and the question arose in my mind and with friends about whether yet another one dealing with racism and prejudice in the South in the Civil Rights era was needed, or would generate any interest. Or, more importantly, have any impact. Then I came across a book by Suzanne W. Jones, emerita professor of English and literature at Johns Hopkins University, titled Race-Mixing: Southern Fiction Since the Sixties. She wrote, “We need these fictions to help us imagine our way out of the social structures and mind-sets that mythologize the past, fragment individuals, pre-judge people, and divide communities.”

Jones quoted the great African-American writer Ralph Ellison, who earlier pointed out in the Southern Literary Journal that the “important role” of this type of fiction is “to tell that part of the human truth which we could not accept or face up to in much of historical writing because of social, racial, and political considerations.”

Jones warned, however, that “while some readers will read themselves, their communities, and race relations anew through this fiction, others reading from old paradigms may misread these new narratives.” Misreadings can occur, she wrote, “when readers…read their [own] formal or ideological presuppositions into texts.” Peter Rabinowitz, a professor of comparative literature at Hamilton College, earlier said much the same thing in a book dealing with narrative elements and techniques and what he called the “politics of interpretation.”

In conversation with and feedback from individuals—white and black—who have read South of Little Rock, I have found examples of all of these scholarly observations. I have found scant misreadings, but I recognize there likely are some of which I am unaware. Chiefly, I have found confirmation that there is both appetite and need for such novels. I have found personal gratification in readers’ appreciation for a story about realistic characters wrestling with social change and learning to see the world around them through fresh perspectives and the eyes of others. And I have found renewed hope in seeing and hearing readers acknowledge the need for all of us to recognize bigotry of all kinds and to combat it in every way possible.