When I was a kid way back in the middle of the last century, someone—I don’t remember who, but likely one of my Southern Baptist Sunday School teachers—said if you told lies, you’d go to hell. If that’s true, the place is going to be so full of snake-oil salesmen, politicians, and internet scam artists that Satan will have to work overtime before he can even think about roasting the rest of us.

I got to thinking about this recently when my cousin David and his wife, neither of whom I had seen in a long time, came to visit. Naturally, we began swapping stories about our childhoods, and while I don’t believe we told each other any lies, we did dial up a bunch of tall tales told to us as children and young adults.

My daddy—I can’t use “father” here because this blog springs from Southern roots—and David’s mother were siblings, and both were great storytellers. In fact, both were what Southerners might describe as “full of it.”

Daddy owned a Western Auto store and for a while had a separate hardware and building supplies store. One of the ways he cultivated customers was spinning yarns around an old upright gas heater in the middle of the Western Auto store. He told them at home, too, and at family get togethers. David’s mother would egg him on and encourage embellishments, which he would repeat later in the store. To be clear, I’m not accusing either of them of lying, especially because she began writing a newspaper column about olden times when she was in her nineties, and the columns that I’ve read were mostly right on.

Daddy owned a Western Auto store and for a while had a separate hardware and building supplies store. One of the ways he cultivated customers was spinning yarns around an old upright gas heater in the middle of the Western Auto store. He told them at home, too, and at family get togethers. David’s mother would egg him on and encourage embellishments, which he would repeat later in the store. To be clear, I’m not accusing either of them of lying, especially because she began writing a newspaper column about olden times when she was in her nineties, and the columns that I’ve read were mostly right on.

However, I must confess that I’ve always been a little dubious about some of the stuff he told, such as how when his equivalent of a junior high school football team filled the helmets of their running backs with helium so they could hurdle the tough linemen on a rival team. Or how one of their ball carriers got so twisted in a huge tackling pileup that he ended up sitting on his own face. Or how when he was a kid and his mother tried to whip him with an elm switch, he grabbed onto her so closely that when she swung at his rear, the switch bent around him, and she only hit herself.

I don’t think for a minute that the Good Lord will send him to hell for telling those stories. Any more than I think He’ll send me for mouthing off at the Vacation Bible School teacher who said that people who hid in storm cellars to escape tornados didn’t believe in God, or something to that effect. She said we should just stay above ground and ask the Lord to protect us from the wind.

Smart aleck that I was, I asked her whether, if she happened to be standing on the railroad tracks when a train was coming, she would move off the tracks or ask God to stop the train. She didn’t appreciate that, nor did my parents when she told them. They also didn’t appreciate my denying having said what I did.

My daddy didn’t appreciate it, either, when my friend and I stole some watermelons and lied about it. Before you stop reading, please remember that teenagers do stupid stuff. I thought it was pretty slick at the time. And come on, this is the South I’m talking about, in the 1950s. It’s not like I’m still doing this stuff.

Anyway, here’s what happened. My friend—another David, coincidentally—and I heard that a particular farmer had hired the former town nightwatchman (a real character, but that’s another story entirely) to guard his watermelon patch at the end of a country road because some boys had been driving down it and “borrowing” watermelons at night. We called them “piss chunks,” by the way. You can imagine why.

Anyway, here’s what happened. My friend—another David, coincidentally—and I heard that a particular farmer had hired the former town nightwatchman (a real character, but that’s another story entirely) to guard his watermelon patch at the end of a country road because some boys had been driving down it and “borrowing” watermelons at night. We called them “piss chunks,” by the way. You can imagine why.

David and I thought it would be fun to see if we could “borrow” some (well, just one each) right under the security guy’s nose by crawling into the field from the back side. Which we did, after using a motorcycle odometer and a compass to work out a triangulated route through some woods from a point we reached by hiking along a railroad track.

The next afternoon about dusk, after we’d done the deed, I was shooting baskets in our yard when Daddy came home from work angry from having heard customers talking about some kids “stealing” watermelons. He asked me if I knew anything about it, and I said I didn’t. Then, almost immediately I sensed that I was found out and had better fess up and apologize right then and there, which I did. Turned out, until that moment he didn’t know a thing about my and David’s little escapade.

It seems that on that same night, some other boys had driven a truck through the edge of another farmer’s patch, smashed a bunch of melons, and driven away with a good number of them. The fact that my transgression was smaller in comparison did nothing to assuage Daddy’s anger or my feelings of guilt. He was so disappointed with me, that he just turned and walked off to our barn to feed our horse.

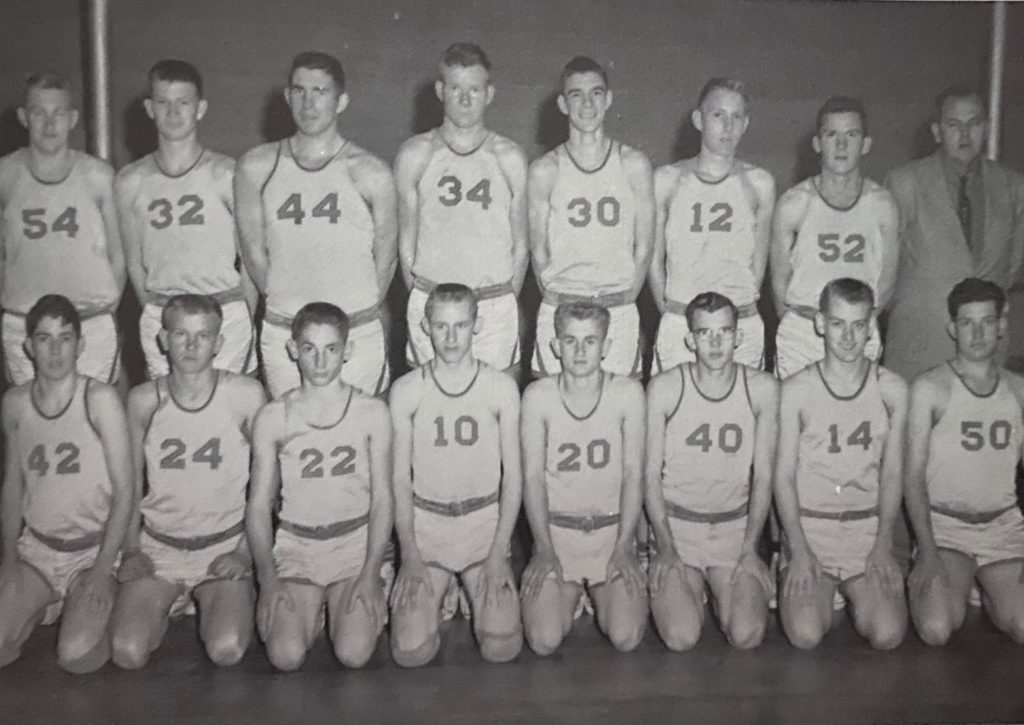

Letting Daddy down was the worst possible punishment for me. If I said that cured me completely, I suppose that would be the best possible ending for this blog. But saying, or even implying, such would be lying again. You see, sometime afterward, the typewriter I was using in typing class happened to break during a long speed-and-accuracy test. Inasmuch as the teacher was way in the back of the room at the time and there was only one other person sitting in my row—one of the aforementioned Davids, not the cousin—I quickly removed the paper from my typewriter and switched my machine with the one in the slot next to me, which happened to be where one of our star basketball players sat the next period. Then I went on to finish my task. (I’m no. 10 in the photo; the “star” is no. 30.)

Letting Daddy down was the worst possible punishment for me. If I said that cured me completely, I suppose that would be the best possible ending for this blog. But saying, or even implying, such would be lying again. You see, sometime afterward, the typewriter I was using in typing class happened to break during a long speed-and-accuracy test. Inasmuch as the teacher was way in the back of the room at the time and there was only one other person sitting in my row—one of the aforementioned Davids, not the cousin—I quickly removed the paper from my typewriter and switched my machine with the one in the slot next to me, which happened to be where one of our star basketball players sat the next period. Then I went on to finish my task. (I’m no. 10 in the photo; the “star” is no. 30.)

A couple of periods later, during chemistry class, the school superintendent—our school was small—appeared in the classroom door with a larger-than-usual frown on his face. “I want Adams,” he said loudly to the chemistry teacher. I knew the reason at once.

There followed a long, silent walk to his office. This was doubly embarrassing and scary because the superintendent and Daddy were good friends, and my mother was a third-grade teacher. This time I didn’t dare fib. All I remember about what followed in the superintendent’s office is that I got off with a stern lecture and a threat of expulsion if anything like that happened again. I’m not saying the superintendent was like the Devil. In fact, he seemed like a bigger and more immediate threat. He never said anything to my parents, though, and I flew right after then. Well, pretty much so.

There followed a long, silent walk to his office. This was doubly embarrassing and scary because the superintendent and Daddy were good friends, and my mother was a third-grade teacher. This time I didn’t dare fib. All I remember about what followed in the superintendent’s office is that I got off with a stern lecture and a threat of expulsion if anything like that happened again. I’m not saying the superintendent was like the Devil. In fact, he seemed like a bigger and more immediate threat. He never said anything to my parents, though, and I flew right after then. Well, pretty much so.

I’m not sure why I thought any of this was worth sharing, and I don’t know whether the Good Lord or Satan either one will pay much attention in the long run. But in the meantime, looking back on all of it, as well as on a few things I’ve left out, has been good for a lot of blood-pressure-reducing chuckles. I’ve drawn on some of Daddy’s stories—for instance, the hot-shot bill collector who appears in South of Little Rock—for material in my novels. And I feel pretty confident that when the time comes, the Devil will be so busy sorting through the ranks of certain former politicians that I and all the others mentioned herein will get through the cooler gate to the hereafter.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.