Recently, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson gave Justice Clarence Thomas and the three justices appointed immediately before her—Neil Gorsuch, Bret Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—a history lesson in “originalism.” But I wonder, will it matter in the long run?

Recently, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson gave Justice Clarence Thomas and the three justices appointed immediately before her—Neil Gorsuch, Bret Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—a history lesson in “originalism.” But I wonder, will it matter in the long run?

Two things got me thinking about this now. One is the background I present on the Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision when I do readings and signings for my novels South of Little Rock and Found in Pieces. The other is the upcoming cycle of midterm elections and continuing efforts to erode the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett consider themselves “originalists” in their view of the Constitution. The simplest definition of originalism is the notion that the Constitution should be read and interpreted based on what the drafters originally intended when they wrote it. Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett all represented themselves as originalists during their confirmation hearings.

Thomas and Gorsuch also consider themselves “textualists,” which is often described as a subset of originalism. Textualists hold that the Constitution should also be interpreted based on the ordinary meaning of the text, or wording, of the document. This means ignoring any factors outside that specific language, such as a particular problem that a passage may be addressing. Originalism and textualism are often lumped together as “strict constructionism,” a broader term applying to almost any conservative approach to the Constitution.

As Federal District Court Judge Jed S. Rakoff explains in his recent New York Review of Books essay about Georgetown law professor Brad Snyder’s new book, Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment, the United States Supreme Court has historically been the most conservative branch of the federal government.

As Federal District Court Judge Jed S. Rakoff explains in his recent New York Review of Books essay about Georgetown law professor Brad Snyder’s new book, Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment, the United States Supreme Court has historically been the most conservative branch of the federal government.

Among case examples that Rakoff cites in support of that view of the Court, several stand out for their relationship to civil rights. Rakoff, who is also an adjunct professor at the Columbia University and New York University law schools, notes that prior to the Civil War, the Court not only rigidly enforced slave laws but declared in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) that even free Blacks were not U.S. citizens. In Minor v. Happersett (1875), the Court upheld Missouri’s denial of the right of women to vote on the grounds that the Constitution made no mention of women voting. And forty years after the Civil War, in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Court legitimized the implementation of Jim Crow laws throughout the South by declaring that “separate but equal” facilities for Blacks and whites were legal under the 14th Amendment. More about that in a moment.

According to Rakoff, it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s, and only then, that the Supreme Court began departing significantly from a conservative bent, with Brown v. Board of Education perhaps the chief example.

The contrast between Plessy (1896) and Brown (1954) is stark and the role of judicial interpretation clear.

Consider this passage in Section 1 of the 14th Amendment: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

In Plessy, the Court ruled that, “The object of the [14th Amendment] was undoubtedly to enforce the equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to endorse social, as distinguished from political equality…. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.”

Only Justice John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky dissented in the 8-1 decision. “Our Constitution is color-blind,” he wrote, “and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” Nevertheless, Plessy stood for almost six decades, enabling a vast array of discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the former slave states and elsewhere.

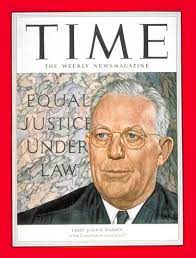

In 1954, the Warren Court, so-called because of the strong influence of Chief Justice Earl Warren, overturned Plessy and ruled in Brown that the plaintiffs in the case—which was a combination of four cases first brought to the Court in 1952—were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.” Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place” because segregated schools are “inherently unequal.”

In 1954, the Warren Court, so-called because of the strong influence of Chief Justice Earl Warren, overturned Plessy and ruled in Brown that the plaintiffs in the case—which was a combination of four cases first brought to the Court in 1952—were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.” Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place” because segregated schools are “inherently unequal.”

Scholars and other Court observers have variously called the Warren years, 1953-1969, a period of “broad constructionism,” “Constitutional Revolution,” or “judicial activism.” Accurate descriptions or not, it was a period when the Court’s rulings tended to reflect the spirit of the times and the needs of the nation as the justices saw them. For example, another prime civil rights-related case of the period was Loving v. Virginia (1967), in which the Court ruled that under the equal protection and due process clauses of the 14th Amendment, laws banning interracial marriage were unconstitutional.

Since Warren’s time, the Court has gradually become more conservative again. Interestingly, Presidents Nixon, Ford, Reagan, and George W. Bush all promised to name “strict constructionist” justices to the Court, and did. But at least two of those—Harry Blackmun and Lewis F. Powell—shifted left to varying degrees once on the bench. Trump made and carried through on the same promise, and so far all three of his appointees are staying the conservative course.

And here’s where enters Justice Jackson’s history lesson, which centers around the 14th Amendment noted above; around the 15th Amendment, which states that, “The rights of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude”; and around the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Passed in the House of Representatives by a vote of 328-72 and in the Senate by a vote of 79-18, and signed by President Lyndon Johnson on August 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act both banned voter restrictive devices like literacy tests and poll taxes and, in its oft-challenged Section 5, declared that certain jurisdictions that had been engaged in discriminatory voting practices over time could not make any changes affecting voting rights without first obtaining the approval of the U.S. Department of Justice or the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

Despite numerous challenges and several legislative updates to the law, Section 5 held fast until 2013, when the Supreme Court declared, by a vote of 5-4 in Shelby County [Alabama] v. Holder that this provision was based on 40-year old data and violated principles of federalism and individual sovereignty of the states. So, the Court said, those historically discriminatory jurisdictions no longer needed to get federal approval to make changes in laws affecting voting rights. Predictably, the decision was followed by several voter restrictive actions across multiple governmental jurisdictions.

Now, the state of Alabama is seeking another change that would further weaken the Voting Rights Act. Consistent with both the 14th and 15th Amendments, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act states that, “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Under this provision, plaintiffs have charged, and prevailed, in multiple instances that state redistricting plans restricting proportional representation for minorities would result in “voter denial” or “voter dilution” and are, therefore, prohibited by law.

Now, the state of Alabama is seeking another change that would further weaken the Voting Rights Act. Consistent with both the 14th and 15th Amendments, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act states that, “No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Under this provision, plaintiffs have charged, and prevailed, in multiple instances that state redistricting plans restricting proportional representation for minorities would result in “voter denial” or “voter dilution” and are, therefore, prohibited by law.

Despite that, in 2021, Alabama created new algorithmically generated Congressional districts that do not take race into account. A suit by a group of Black voters challenging this action has now reached the U.S. Supreme Court in Merrill v. Milligan. The case is there because the conservative justices on the Court voted to hear it on appeal after a federal district court panel ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. The Court recently heard oral arguments in the case but has yet to rule.

If allowed to stand, Alabama’s redistricting plan would mean the state’s historic Black Belt area would be represented by only one of the state’s seven Congressional districts, even though Black Alabamians make up 27 percent of the state’s electorate.

When the Supreme Court heard arguments in the case recently, Justice Jackson used an “originalist” argument to question the legality of Alabama’s attempt at race-neutral redistricting. Asserting that the authors of the 14th and 15th Amendments wrote them “in a race-conscious way,” Jackson said that she had gone back and “looked at the report that was submitted by the Joint [Congressional] Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the 14th Amendment, and that the document stated that the entire point of the amendment was to secure the rights of the freed former slaves.” The entire history of how the 14th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act came into existence demonstrate that they were “race-conscious” efforts, Jackson said.

When the Supreme Court heard arguments in the case recently, Justice Jackson used an “originalist” argument to question the legality of Alabama’s attempt at race-neutral redistricting. Asserting that the authors of the 14th and 15th Amendments wrote them “in a race-conscious way,” Jackson said that she had gone back and “looked at the report that was submitted by the Joint [Congressional] Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the 14th Amendment, and that the document stated that the entire point of the amendment was to secure the rights of the freed former slaves.” The entire history of how the 14th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act came into existence demonstrate that they were “race-conscious” efforts, Jackson said.

Among other remarks, Jackson also quoted Civil War-era Congressional leader and Joint Committee member Thaddeus Stevens indicating that the whole purpose of the 14th Amendment was to stop the former Confederate states from depriving Black men and women of rights and equality. In advocating for the amendment, Stevens said, “Unless the Constitution should restrain them, those states will all, I fear, keep up this discrimination and crush to death the hated freedmen.”

Jackson’s history lesson was as solid an “originalist” exposition as one can imagine. The intent of Congress in adopting the 14th and 15th Amendments is clear and undeniable. And now it remains to be seen how the self-identified conservative “originalists” on the Court will vote on Merrill v. Milligan.

Sources for this blog include the texts of the cited laws and court cases; Jed S. Rakoff, “A Prisoner of His Own Restraint,” New York Review of Books, 69, no. 17 (2022), 39-42; various other published articles; and reporting on Justice Jackson by Paul Blumenthal of the Huffington Post.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.