While I was writing Found in Pieces—my second novel about the 1950s South—no one asked me why I chose a woman newspaper editor as the main character. But if they had, I would have said, “Because she made me do it.” By “she,” I mean the fictitious character I created initially for a lesser role in my first novel. Really. I’m serious. She made me learn a lot too.

Here’s how it happened and some of what I discovered.

One of the key secondary characters in my previous novel, South of Little Rock, set in the fictional small town of Unionville, was the unsavory editor of the local weekly. I based the physical setting of his paper on a real one I recalled from my early childhood.

In those days, my father had a store next door to the newspaper office, and the editor, who was an upstanding fellow unlike the one in my novel, had a female assistant who had a daughter my age. She and I sometimes played together in the newspaper building, as well as in my father’s store and in the alleyway out back.

I was intrigued by the printing press and all the trays of type in the newspaper office and thought my friend’s mother had a truly neat job. So, in the novel I made the fictional editor’s assistant a woman with daughters. In the course of fleshing out the story, I grew to like the character a lot. I even named her “Pearl” after an aunt who had taken to writing a weekly newspaper column when she was well past 80.

Later, when I decided to write a follow-on novel set in the same fictional town a bit later, it was easy to envision making the local paper a central focus with Pearl now at the helm. Her role in the first novel seemed to demand this larger platform. So I gave it to her. And I made her the owner as well as the editor.

Later, when I decided to write a follow-on novel set in the same fictional town a bit later, it was easy to envision making the local paper a central focus with Pearl now at the helm. Her role in the first novel seemed to demand this larger platform. So I gave it to her. And I made her the owner as well as the editor.

I already knew that few women owned or edited newspapers before or during the 1950s, but to ensure that I made Pearl authentic, I wanted to learn more. You could say that Pearl, whom I also made a former teacher, sent me back to school. Here are some of the pioneering newspaperwomen that I “met” along the way.

Elizabeth Timothy was a pregnant mother of six in colonial Charleston (then Charles Town), South Carolina, when she became America’s first female editor and publisher on January 4, 1739. She assumed management of the South-Carolina Gazette following the unexpected death of her husband Lewis Timothy a few days earlier, at Christmastime. Lewis had worked previously for Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, and Franklin was one-third owner of the Charleston paper. The partnership agreement called for Lewis’s oldest son, Peter, to manage the paper if anything happened to Lewis down the road, but when he died prematurely, Peter was only thirteen.

Elizabeth Timothy was a pregnant mother of six in colonial Charleston (then Charles Town), South Carolina, when she became America’s first female editor and publisher on January 4, 1739. She assumed management of the South-Carolina Gazette following the unexpected death of her husband Lewis Timothy a few days earlier, at Christmastime. Lewis had worked previously for Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, and Franklin was one-third owner of the Charleston paper. The partnership agreement called for Lewis’s oldest son, Peter, to manage the paper if anything happened to Lewis down the road, but when he died prematurely, Peter was only thirteen.

With consent from Franklin, Elizabeth took over the paper’s operations, but to honor the contract she listed Peter Timothy as “Printer” on the masthead of her first and subsequent editions. She told her readers that she was in charge, however, and she assured them that she had been working alongside her husband and knew what she was doing. In addition to running the paper until turning it over to Peter when he became 21, Elizabeth Timothy also printed books and pamphlets and earned enough money for her family to buy out Franklin’s interest in the enterprise. After Peter took over operations, Elizabeth opened a bookstore next door to the printing shop.

Anne Newport Royall went from working as a household servant alongside her widowed mother in 1790s western Virginia to become America’s first female travel writer, and subsequently a crusading political journalist and newspaper publisher. Tutored by her well-to-do employer, veteran Revolutionary War officer William Royall, she eventually married him. When he died after only a few years of marriage, a family dispute over his will cost Anne most of what he had bequeathed to her.

Anne Newport Royall went from working as a household servant alongside her widowed mother in 1790s western Virginia to become America’s first female travel writer, and subsequently a crusading political journalist and newspaper publisher. Tutored by her well-to-do employer, veteran Revolutionary War officer William Royall, she eventually married him. When he died after only a few years of marriage, a family dispute over his will cost Anne most of what he had bequeathed to her.

She then used much of the funds she retained to travel around the South and, in 1724, to Washington, DC. There she lobbied Congress and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to recognize a widow’s right to her husband’s wartime pension. She finally obtained it after Congress passed a new pension law twenty-four years later, in 1848. In the meantime she resumed and extended her travels across the country and supported herself in part by writing travel books and selling them on subscription.

Also during that interim, she established in 1831 a Washington newspaper titled Paul Pry, coincident with the widespread popularity of a British play about a meddlesome English busybody. Royall’s announced purpose for the paper was to expose political corruption and fraud, which she did vociferously, often in acerbic and accusatory language. So much so, that she was publicly derided as a “common scold.” Undaunted, she replaced Paul Pry with The Huntress in 1836 and continued railing against anything she considered graft, nepotism, or fraud in government.

Sarah Josepha Hale, known to many today only as the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” began her professional life as a New Hampshire schoolteacher. In 1813 she married an attorney and they had five children by the time he died in 1822. From then until the end of her life, she dressed only in black. In 1823, with financial backing from her late husband’s Freemason lodge, she published a collection of poems, The Genius of Oblivion. It was the first of 50 some titles she penned before her death in 1879.

Sarah Josepha Hale, known to many today only as the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” began her professional life as a New Hampshire schoolteacher. In 1813 she married an attorney and they had five children by the time he died in 1822. From then until the end of her life, she dressed only in black. In 1823, with financial backing from her late husband’s Freemason lodge, she published a collection of poems, The Genius of Oblivion. It was the first of 50 some titles she penned before her death in 1879.

In 1827 her first novel, Northwood: Life North and South, made her one of the first female American novelists and one of the first American fictionists to write about slavery, which she opposed. She exerted her greatest influence on American life, however, as editor of the Philadelphia-based Godey’s Lady’s Book, a position she accepted in 1837 and held for 40 years, until age 89. With a circulation of more than 150,000, the magazine carried stories and articles by many of the nation’s leading thinkers, activists, and writers, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Washington Irving, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Catherine Beecher, and Emma Willard.

With this platform, Hale became one of the primary arbiters of American culture. She was one of the leading advocates for Lincoln’s making Thanksgiving a national holiday. She campaigned for the preservation of Mount Vernon. And she pushed for women’s right to own property and have access to higher education. At the same time, however, she did not support women’s suffrage and, despite her own position, encouraged women to stick to domestic roles in society.

Amelia Jenks Bloomer may be most celebrated for popularizing a form of Turkish dress that became known across America as “bloomers,” initially pantaloons or trousers worn under a skirt that was short for the times. First widely donned in the 1850s, bloomers became for many a symbol of both the temperance and the women’s suffrage movements.

Amelia Jenks Bloomer may be most celebrated for popularizing a form of Turkish dress that became known across America as “bloomers,” initially pantaloons or trousers worn under a skirt that was short for the times. First widely donned in the 1850s, bloomers became for many a symbol of both the temperance and the women’s suffrage movements.

Arguably the most important thing Bloomer did for women’s suffrage, however, was to introduce Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Susan B. Anthony in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, the year of the Women’s Rights Convention. There, a year later, Bloomer launched The Lily, the first American newspaper published by a woman expressly for women. She served as owner, editor, and publisher until selling the paper in the mid-1850s. It continued in print until after the Civil War.

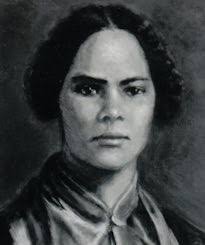

Mary Ann Shadd Cary began life in Delaware in 1823, the daughter of Black abolitionists and oldest of 13 children. She grew up in Pennsylvania, attended a Quaker Boarding School, and later taught Black children in that state, New York, and Delaware. When the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made all free African Americans likely prey for slave hunters, she and a brother emigrated to Canada. There in 1853, three years before marrying Thomas F. Cary, she founded the Provincial Freeman, that country’s first abolitionist newspaper.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary began life in Delaware in 1823, the daughter of Black abolitionists and oldest of 13 children. She grew up in Pennsylvania, attended a Quaker Boarding School, and later taught Black children in that state, New York, and Delaware. When the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made all free African Americans likely prey for slave hunters, she and a brother emigrated to Canada. There in 1853, three years before marrying Thomas F. Cary, she founded the Provincial Freeman, that country’s first abolitionist newspaper.

As the first Black female newspaper editor in North America, Cary supported women’s rights and the abolition of slavery, reported on prominent activists such as Lucy Stone Blackwell and Lucretia Mott, and lectured herself throughout Canada and the U.S., chiefly to encourage Blacks in the U.S. to move north.

Prior to the Civil War, she met John Brown in Canada, and when war broke out, she returned to the U.S. and became a recruiting officer for the Union Army. When her husband died sometime before Appomattox, she moved to the District of Columbia where she taught school again for several years. After the war, she attended Howard University and became one of the first Black American women to earn a law degree.

In addition to their pioneering roles in journalism and to whatever else they might have had in common, all of these women also possessed unfettered determination and grit and well deserve our celebrating their achievements. I will share additional pioneering newspaperwomen’s stories in a future post.

Online sources for this post include: National Women’s History Museum, National Park Service, New York State Library, Library of Congress, Library and Archives of Canada, and Wikipedia.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.