There is a scene in my novel Found in Pieces where Pearl Goodbar, the story’s main character, gets to hear two of her journalism role models speak at an event that actually occurred in real life. Although both of those journalists were historical figures, both are also men, so they don’t appear in this post.

Another of the fictional Pearl’s real contemporaries—someone she knows about but never meets—does show up in Found in Pieces, however. And Pearl is not the only fictional character in the novel who knew of her. I can’t say more about that here, though, lest I spoil the story for any who haven’t read it.

Another of the fictional Pearl’s real contemporaries—someone she knows about but never meets—does show up in Found in Pieces, however. And Pearl is not the only fictional character in the novel who knew of her. I can’t say more about that here, though, lest I spoil the story for any who haven’t read it.

Without further prologue, here is my final blog about pioneering newspaperwomen who paved the way for Pearl. Most of the women in this grouping did not own or edit newspapers, but they left huge marks on the industry, especially in investigative and war reporting.

Elizabeth Jane Cochran was dubbed Nelly Bly by the editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch when she turned in her first article—a piece that argued for divorce law reform in 1880. As one of 15 children and step-children whose father died when she was 6, Bly could not afford college. She landed the Dispatch job by submitting an eye-grabbing response to a piece posturing that the proper role for women was in the home and not the workplace. After she wrote a series of articles about poor working conditions for women in factories, the paper received so many complaints that the editor reassigned her to cover topics like fashion and gardening.

Agitated, bored, and still only 21, Bly finagled assignment to Mexico, where she lived for six months and sent back stories about Mexican lives, customs, and government. When she criticized dictator Porfirio Díaz, however, she had to flee the country to avoid arrest. Assigned subsequently to theater and arts reporting, Bly quit the Dispatch, went to Manhattan, and got a job on the New York World. There she feigned mental illness, got herself sent to an asylum, stayed ten days, produced a sensational exposé about the despicable conditions, then turned that work into a book. The next year, 1889, she proposed and carried out the stunt that made her name a household word—an attempt to travel around the world faster than the 80 days in which Jules Verne’s fictional Phileas Fogg did. She made it in 72 days.

Agitated, bored, and still only 21, Bly finagled assignment to Mexico, where she lived for six months and sent back stories about Mexican lives, customs, and government. When she criticized dictator Porfirio Díaz, however, she had to flee the country to avoid arrest. Assigned subsequently to theater and arts reporting, Bly quit the Dispatch, went to Manhattan, and got a job on the New York World. There she feigned mental illness, got herself sent to an asylum, stayed ten days, produced a sensational exposé about the despicable conditions, then turned that work into a book. The next year, 1889, she proposed and carried out the stunt that made her name a household word—an attempt to travel around the world faster than the 80 days in which Jules Verne’s fictional Phileas Fogg did. She made it in 72 days.

In 1895, at age 31, Bly married a 73-year-old millionaire manufacturer of steel containers, and when he died in 1904, she took over management of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. That same year, Iron Clad began making a steel barrel that became the model for the 55-gallon drum still used today. Unfortunately for Bly, that did not keep the company from going bankrupt. Eventually, she returned to reporting, going to the Eastern Front during World War I and writing about women’s suffrage afterward.

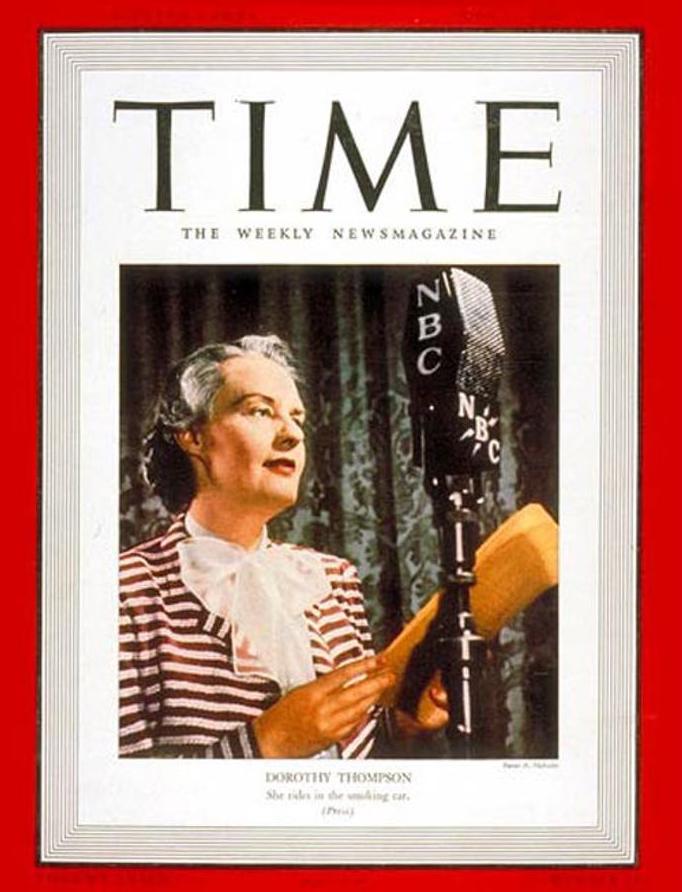

Dorothy Celene Thompson was not a person Pearl would have liked had they met. They held decidedly different views about Black Americans. Born in Western New York in 1893 and educated in politics and economics at Syracuse University, Thompson began her professional life working for women’s suffrage in Buffalo. She launched her journalism career in Europe in the early 1920s as a correspondent for Philadelphia’s Public Ledger and soon became the first American woman to run a major foreign news bureau, that of the New York Post in Berlin. In the mid-1930s, she returned to the U.S. to work at the New York Tribune and began an “On the Record” column that was eventually syndicated to more than 170 papers. She also became a highly popular news commentator at NBC radio.

In between all of that, she married Sinclair Lewis (the second of three husbands), had a same-sex affair with German author Christa Winsloe, and got expelled from Germany for criticizing Adolf Hitler after interviewing him. In a subsequent book titled I Saw Hitler, she famously called him “inconsequent and voluble, ill poised and insecure…the very prototype of a little man.”

In between all of that, she married Sinclair Lewis (the second of three husbands), had a same-sex affair with German author Christa Winsloe, and got expelled from Germany for criticizing Adolf Hitler after interviewing him. In a subsequent book titled I Saw Hitler, she famously called him “inconsequent and voluble, ill poised and insecure…the very prototype of a little man.”

Thompson never owned or edited a newspaper, but in 1939, she made the cover of Time magazine, and the article about her inside that issue called her and Eleanor Roosevelt the two most influential women in America. Like my fictional Pearl Goodbar, however, Eleanor Roosevelt would never have said of Black voters what Thompson wrote of them during the presidential election of 1936. She opined that they constituted a bloc “notoriously venal. Ignorant and illiterate, the vast mass of them . . . ‘bossed’ and ‘delivered’ in blocs by venal leaders, white and black.”

Martha Ellis Gellhorn also never owned or edited a newspaper, but she was one of the most important war correspondents of the 20th century and loomed almost larger than life in the industry. The daughter of a prominent St. Louis physician and an influential social reformer, Gellhorn left Bryn Mawr College in 1927 without graduating. Over the next several years she found work writing for a variety of magazines and newspapers in both the U.S. and Europe. In France, she worked for the United Press news service until she was fired for complaining of sexual harassment.

Martha Ellis Gellhorn also never owned or edited a newspaper, but she was one of the most important war correspondents of the 20th century and loomed almost larger than life in the industry. The daughter of a prominent St. Louis physician and an influential social reformer, Gellhorn left Bryn Mawr College in 1927 without graduating. Over the next several years she found work writing for a variety of magazines and newspapers in both the U.S. and Europe. In France, she worked for the United Press news service until she was fired for complaining of sexual harassment.

Over the next several years she worked for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration helping to document the effects of the Great Depression, lived for a time at the White House helping Eleanor Roosevelt write a daily column for Woman’s Home Companion, and wrote the first two of the more than 15 books of fiction and non-fiction that she turned out in her lifetime.

In the mid-1930s, Gellhorn met Ernest Hemingway, to whom she was eventually married for a while, and traveled with him to Spain, where she reported on the Spanish Civil War. In later years, she reported importantly on nearly every significant American military conflict. When the army frowned on allowing women reporters near the front lines in WWII, she finagled her way onto a D-Day hospital ship and went ashore with medical personnel. She witnessed the Allied liberation of the Dachau concentration camp, reported on the Nuremberg war trials, and later covered the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam and the U.S. invasion of Panama. Along the way, she divorced Hemingway and married a former managing editor of Time. In 1998, nearly blind and suffering from incurable cancer, she took her own life.

Marguerite Higgins came to reporting on American wars later than Martha Gellhorn, but their careers overlapped. Higgins was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence, which she received in 1951 for her coverage of the Korean War. Born in Hong Kong in 1920 to a French woman and an American shipping company executive, Higgins worked on several newspapers while a student at Cal-Berkeley, including editing the university’s Daily Californian for a time. Upon graduating, she moved to New York and earned a master’s in journalism at Columbia.

Marguerite Higgins came to reporting on American wars later than Martha Gellhorn, but their careers overlapped. Higgins was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Foreign Correspondence, which she received in 1951 for her coverage of the Korean War. Born in Hong Kong in 1920 to a French woman and an American shipping company executive, Higgins worked on several newspapers while a student at Cal-Berkeley, including editing the university’s Daily Californian for a time. Upon graduating, she moved to New York and earned a master’s in journalism at Columbia.

After grad school, she snagged a war correspondent’s job with the New York Herald Tribune, and like Gellhorn, she eventually covered the liberation of Dachau and the Nuremberg war trials. In 1950, Higgins became chief of the Tribune’s Far East bureau in Tokyo, which soon put her in the middle of the conflict in Korea. After she narrowly escaped entrapment on the wrong shore when South Korean troops destroyed a bridge on the Han River in Seoul, the American general in the area banned women correspondents. Higgins appealed to the man’s superior, General Douglas MacArthur, and he rescinded the order.

In addition to the Pulitzer, Higgins received numerous other awards for her wartime reporting. Afterward, she wrote for Collier’s magazine, headed the Tribune’s Moscow bureau, worked for Newsday, covered the Congolese civil war, and wrote three best-selling books about her experiences. In the early 1960s, her reporting included interviews with numerous world leaders, among them Nikita Khrushchev and Jawaharlal Nehru. Higgins died when she was only 45, after contracting leishmaniasis from parasites while covering the war in Vietnam.

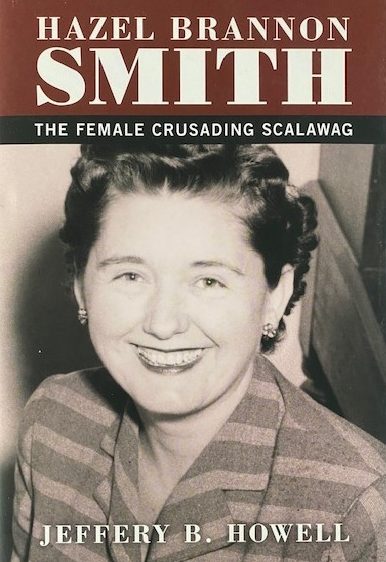

Hazel Brannon Smith is the historic newspaperwoman that has the most in common with my fictional character. Pearl is not modeled on Smith, but there are similarities. Born in 1914, Hazel was the eldest child of an electrical contractor, who, though a segregationist, raised his children to be civil in their dealings with Black Americans. She graduated from Gadsden (Alabama) High School at age 16, went to work immediately for the weekly Etowah Observer, and quickly decided that she wanted to own a newspaper. At 18 she entered the University of Alabama to study journalism and soon became editor of the school newspaper.

A year after her graduation in 1935, while still only 22, Hazel wrangled a bank loan to buy the Durant News in rural Holmes County, Mississippi, and became not only the owner, but also the editor and publisher. Eight years later, in 1944, she bought the nearby Lexington Advertiser, and in 1956, she purchased the Northside Reporter in Jackson and the Banner County Outlook in Flora. Along the way, in 1950, she married Walter Dyer Smith, a ship’s purser she met on a world cruise.

A year after her graduation in 1935, while still only 22, Hazel wrangled a bank loan to buy the Durant News in rural Holmes County, Mississippi, and became not only the owner, but also the editor and publisher. Eight years later, in 1944, she bought the nearby Lexington Advertiser, and in 1956, she purchased the Northside Reporter in Jackson and the Banner County Outlook in Flora. Along the way, in 1950, she married Walter Dyer Smith, a ship’s purser she met on a world cruise.

Four years later, in 1954, came the Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring school desegregation illegal. That and the shooting of a retreating Black man by a white sheriff in Holmes County marked the start of a change in Smith’s editorial policy. Despite being raised to treat Blacks with civility, she had until then opposed integration.

When Smith began decrying violence by extremist groups and refused to support the White Citizens’ Council, the local chapter got her husband fired from his job and launched a competing countywide newspaper. She continued supporting integration anyway and welcomed Freedom Riders into her home in 1964. That inspired a cross burning, the bombing of her office, and a threat on her life. She persisted in her views nevertheless and became the first woman to receive a Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing. Shunned by friends and long-time advertisers, Smith continued in the newspaper business well into the 1970s but eventually lost nearly all that she owned. She died broke in a nursing home in Tennessee in 1994.

Smith concludes my three-part list of real newspaperwomen who paved the way for my fictional one. I purposely did not include Katharine Graham, long-time owner and publisher of the Washington Post because she did not manage that paper prior to the time in which Found in Pieces is set. Graham’s wealthy father acquired the paper at a bankruptcy auction in 1935 and turned the reins over to Katharine’s husband Philip in 1946. Katharine took over after Philip committed suicide with a shotgun in 1963, following a nervous breakdown, and served initially as publisher and then chair of the board until 1991. Though long a force on the Washington social and political scenes, she is probably best known for heading the Post during the Watergate conspiracy and the demise of Richard Nixon.

All of the women on my list merit our remembering them and revisiting their lives and achievements. Many are the subjects of book-length biographies, and movies have been made and plays produced about a number of them. Some are in the National Women’s Hall of Fame. And there is a plethora of information about them in the pages (online and on paper) of all sorts of encyclopedias and histories of journalism and other aspects of our national life. If you pay any of them a longer visit, you will be rewarded with inspiration.

Online sources for this post include: National Women’s History Museum, Library of Congress, State Historical Society of Missouri, Encyclopedia of Alabama, Mississippi History Now, Britannica Explores, History.net, and Wikipedia.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.