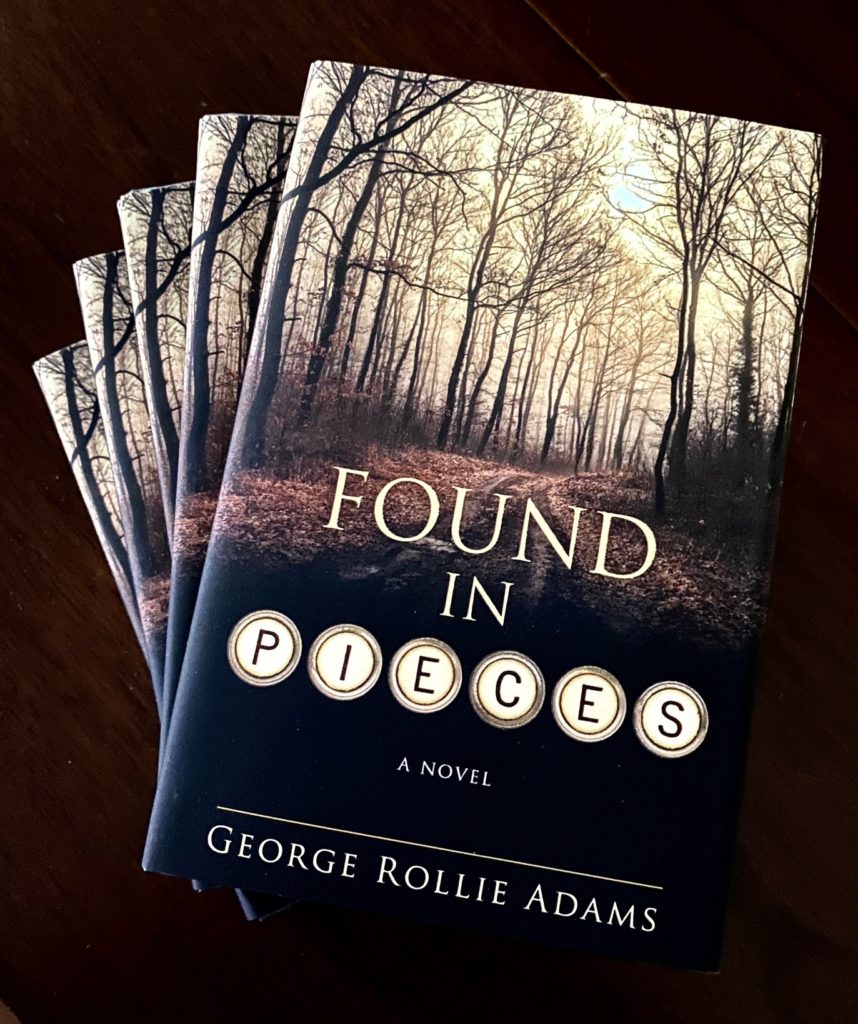

The first line of my novel Found in Pieces identifies Pearl Goodbar as the new owner and editor of a weekly newspaper, the Unionville Times, in 1958. That responsibility alone would have been challenge enough at a time when few women owned or edited newspapers.

But that was not the only obstacle staring her in the face. She also had serious money problems. She and her husband had borrowed heavily to buy the paper, and now he had lost the outside job they thought would help them make a go of it.

To compound her woes, when public tension over school desegregation rose to a new level, Pearl ran up against editorial decisions that could drain off critically needed operating revenue.

To compound her woes, when public tension over school desegregation rose to a new level, Pearl ran up against editorial decisions that could drain off critically needed operating revenue.

In those days, most white-owned newspapers all across the country followed a generally accepted standard for dealing with race. They didn’t mention Black people except in the context of some sort of violence—an accident or a crime—and even then rarely by name.

When white papers did print a Black person’s name, they also printed the person’s race. A few papers even had separate sections for white news and Black news.

Black leaders had been complaining for years that racial labels in crime stories harmed overall public perceptions of Black people. In 1946, when the New York Times became the first major newspaper to omit racial labels, its decision was so startling that Time magazine reported it in its pages.

The Times’ example brought a few other papers around, but progress proved slow. In 1952, a Georgia newspaper’s survey of 34 dailies in the Deep South showed that only half used courtesy titles when referring to Blacks. Three years later, a survey by Jet magazine found that only a minority of white-owned newspapers anywhere in the United States ran obituaries or social, civic, church, or business news about Blacks.

Ira Harkey, editor of the Pascagoula Chronicle in Mississippi, was one of the first Southern editors to depart from this practice. For a while, his readers didn’t even notice. In 1950, when he ran a story about a local man severely beating his son, the national wire services picked it up, and letters of sympathy for the family poured in from far and wide. Those stopped abruptly, however, after the Associated Press got hold of a photo of the boy, and readers learned that he was Black. One subscriber wrote that if Harkey was going to write about Blacks—not the word the man used—he needed to call them that right up front, “so I don’t waste my time reading about ‘em.”

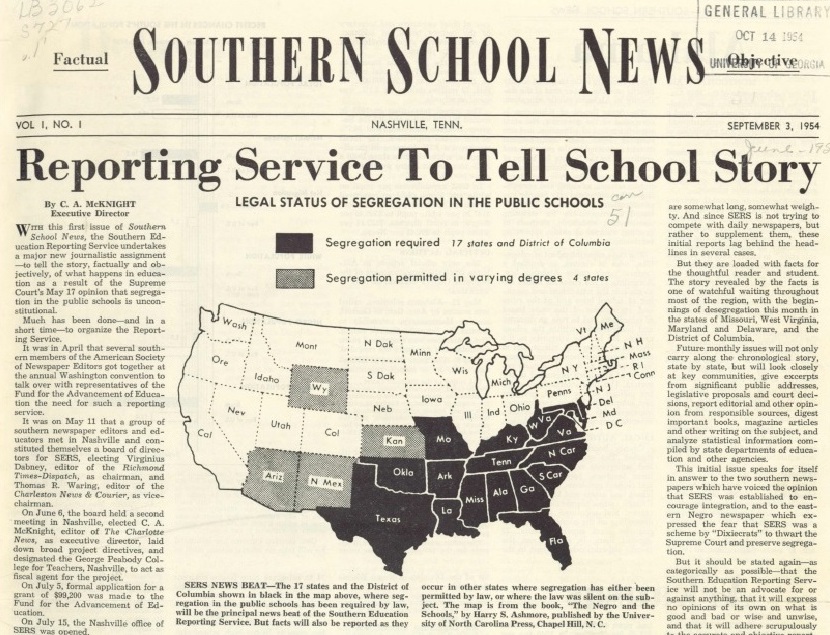

Fortunately, Harkey was not alone among editors advocating for change. In 1954, the year of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, the newly formed Southern Education Reporting Service (SERS), led chiefly at the start by Harry Ashmore of the Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock, took on a role that traditional, community-based Southern papers would not.

Fortunately, Harkey was not alone among editors advocating for change. In 1954, the year of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, the newly formed Southern Education Reporting Service (SERS), led chiefly at the start by Harry Ashmore of the Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock, took on a role that traditional, community-based Southern papers would not.

The journalists and educators on SERS’s region-wide board thought newspapers reported too much on the day-to-day difficulties of desegregation in their individual locales and too little on the long-term successes of integration in other places—places where desegregation seemed to be working. Or, put another way, too much time and space on events that sparked crises and too little on societal change.

Through its Southern School News, SERS published in-depth monthly reports and statistics about progress toward integration in districts throughout the South. The specialty paper had reporters in 17 Southern and border states and the District of Columbia. Eventually, its subscribers numbered more than 30,000 educators, journalists, public officials, and libraries.

Through its Southern School News, SERS published in-depth monthly reports and statistics about progress toward integration in districts throughout the South. The specialty paper had reporters in 17 Southern and border states and the District of Columbia. Eventually, its subscribers numbered more than 30,000 educators, journalists, public officials, and libraries.

Most Southern papers still refused to change, however, and the few that did were chiefly in the upper South—Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. There, some papers recognized the legality of Brown v. Board of Education but urged a “go-slow” approach toward compliance. In the Deep South, most papers resisted any degree of compliance, and the majority openly opposed desegregation.

Overall, white-owned newspaper coverage of racial issues and desegregation remained sparse throughout the country until the murder of Emmitt Till and subsequent trial of his killers in 1956. A journalist writing that year in Time magazine said that until then, Southern papers had been doing “a patchy, pussyfooting job of covering the region’s biggest running story since slavery.”

It’s difficult to avoid connecting at least some of this spottiness to the changing nature of newspapers and newspaper ownership. In 1947, two years after the end of World War II, there were 1,769 daily papers in the United States, nearly 2,000 fewer than before the war, with 80% of those being delivered in the afternoon. Now, too, fewer owners and publishers had backgrounds in journalism. Increasing numbers of them came from the corporate sector, with interests that trended more heavily to power and prestige. All were dependent upon subscribers and advertisers for revenue. That meant needing to keep them satisfied about content.

Large-scale coverage of desegregation didn’t really take hold until Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard to resist the integration of Little Rock Central High School and President Eisenhower sent elements of the army’s 101st Airborne Division to enforce it in 1957. That crisis has been called the “first great media event” of the Civil Rights movement. When Faubus mobilized the Guard, there were 5 out-of-town reporters in Little Rock. Four weeks later there were 225. NBC News anchor John Chancellor quipped that Little Rock had been “transformed into a kind of giant press room.”

Nevertheless, the majority of Southern newspapers and their editors continued to struggle with change. Over the next seven years, however, six determined Southern editors received Pulitzer Prizes for reporting and editorializing in opposition to segregation and in support of Brown v. Board of Education: Ashmore in 1958, Buford Boone of the Tuscaloosa News in 1957, Ralph McGill of the Atlanta Constitution in 1959, Lenoir Chambers of the Norfolk Virginia-Pilot in 1963, and Hazel Brannon Smith of the Lexington (Mississippi) Advertiser in 1964.

Nevertheless, the majority of Southern newspapers and their editors continued to struggle with change. Over the next seven years, however, six determined Southern editors received Pulitzer Prizes for reporting and editorializing in opposition to segregation and in support of Brown v. Board of Education: Ashmore in 1958, Buford Boone of the Tuscaloosa News in 1957, Ralph McGill of the Atlanta Constitution in 1959, Lenoir Chambers of the Norfolk Virginia-Pilot in 1963, and Hazel Brannon Smith of the Lexington (Mississippi) Advertiser in 1964.

Another editor with similar backbone, Harding Carter, Jr., editor of the Greenville (Mississippi) Delta Democrat-Times, had earlier, in 1946, received a Pulitzer for writing about intolerant treatment of Japanese-American soldiers after World War II. Now he came down hard on White Citizens’ Councils. Two years before the Little Rock Central crisis, he attacked them in an article for Look magazine titled “A Wave of Terror Threatens the South.”

With opponents of integration organizing more and more chapters of this new anti-integration organization across the South, the Mississippi State House of Representatives, by a vote of 89-19, passed a resolution calling Carter a liar. He responded by expressing hope that “this fever like Ku Kluxism which rose from the same kind of infection, will run its course before too long a while.” In the meantime, he said, “Those 89 character mobbers can go to hell collectively or singly and wait there until I back down. They needn’t plan on returning.“

With opponents of integration organizing more and more chapters of this new anti-integration organization across the South, the Mississippi State House of Representatives, by a vote of 89-19, passed a resolution calling Carter a liar. He responded by expressing hope that “this fever like Ku Kluxism which rose from the same kind of infection, will run its course before too long a while.” In the meantime, he said, “Those 89 character mobbers can go to hell collectively or singly and wait there until I back down. They needn’t plan on returning.“

These editors along with a handful of others remained a minority in the South for a long while. That is where Southern newspaper reporting on desegregation stood when my fictional Pearl Goodbar assumed the reins of the Unionville Times. Found in Pieces tells the story of how she responded to the challenges that situation presented.

Sources for this post include: Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation; and the chapter on newspapers and civil rights in David R. Davies’s 1997 PhD dissertation on the post-war decline of American newspapers.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.