Because she died when I was young, I have no personal recollection of my Great-grandmother Henrietta McCullar. Most of the little I know of her comes from a few stories my mother told me, two old sepia photographs, and an Eight-Point Star quilt Henrietta made sometime around 1900.

Because she died when I was young, I have no personal recollection of my Great-grandmother Henrietta McCullar. Most of the little I know of her comes from a few stories my mother told me, two old sepia photographs, and an Eight-Point Star quilt Henrietta made sometime around 1900.

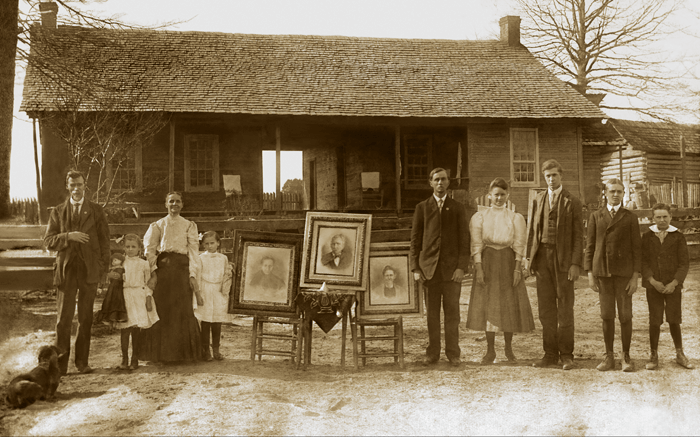

My mother once took me to visit another of her older relatives who also lived in a northern-Louisiana dogtrot house—so called because a dog could trot through the breezeway connecting the two sides—like the one in this photograph with Henrietta, her husband George, and their children. I never saw this house, but the photograph hangs in my study with other family photos, and the quilt rests on my late mother’s rocking chair not far from a quilt my wife made.

Today, we use cameras in our smartphones to document our lives in unprecedented degree—excessively so, many would argue. But from before the Civil War to well into the 1900s, when few people could afford cameras of their own, itinerant photographers traveling the country, first by wagon and rail and later by car, were a principal source of photographs for families across America, enabling them to capture and preserve memories for themselves and their descendants.

One of the things I like about this early twentieth-century photograph is the way it gathers images of past and present generations together. Henrietta and her family not only put on their best Sunday-go-to-meeting clothes for the photographer, but they also brought out portraits of family members who had gone before. Families posing this way in front of their homes was a common practice of the period, and I feel fortunate to have examples from other ancestors as well.

As much as I prize the photograph, though, I prize the quilt more. In Henrietta’s day and still in our time, though less so now, quilters often put themselves and family members in their quilts by cutting pieces of material from clothing no longer fit for wearing. I don’t know which of Henrietta’s family members are represented in her quilt, or even for certain that any are. But the times, the family’s somewhat limited means, and some of the cloth itself suggests that likely is the case.

As much as I prize the photograph, though, I prize the quilt more. In Henrietta’s day and still in our time, though less so now, quilters often put themselves and family members in their quilts by cutting pieces of material from clothing no longer fit for wearing. I don’t know which of Henrietta’s family members are represented in her quilt, or even for certain that any are. But the times, the family’s somewhat limited means, and some of the cloth itself suggests that likely is the case.

I like to think it is anyway, and I often look at the photograph and the quilt together, realize that I am related to all of the people represented in them, and try to imagine their lives beyond the meager knowledge I have of them. Such effort does little or nothing to increase what I know of them, but it makes me feel good, and I wish I could tell Henrietta that. But, then, maybe she knew something like this would happen when she gathered her family, lined them up, and posed with them under a hot sun. And maybe she knew it, too, when around that same time she patiently cut and stitched all those tiny pieces of fabric for the quilt that is as beautiful and vibrant today as when she made it all those years ago.

To be notified of new posts, please email me.