He warned me. I give him that. And he didn’t punish me, and I was grateful for that. I still have a scar from the experience, though. I see it every time I eat, wash my hands, or turn a page in a book. I don’t see it, however, when I’m down on my knees in the garden, the way I was when I got it—on my knees I mean. But that’s only because now I wear gloves when I’m down there.

Here’s what happened.

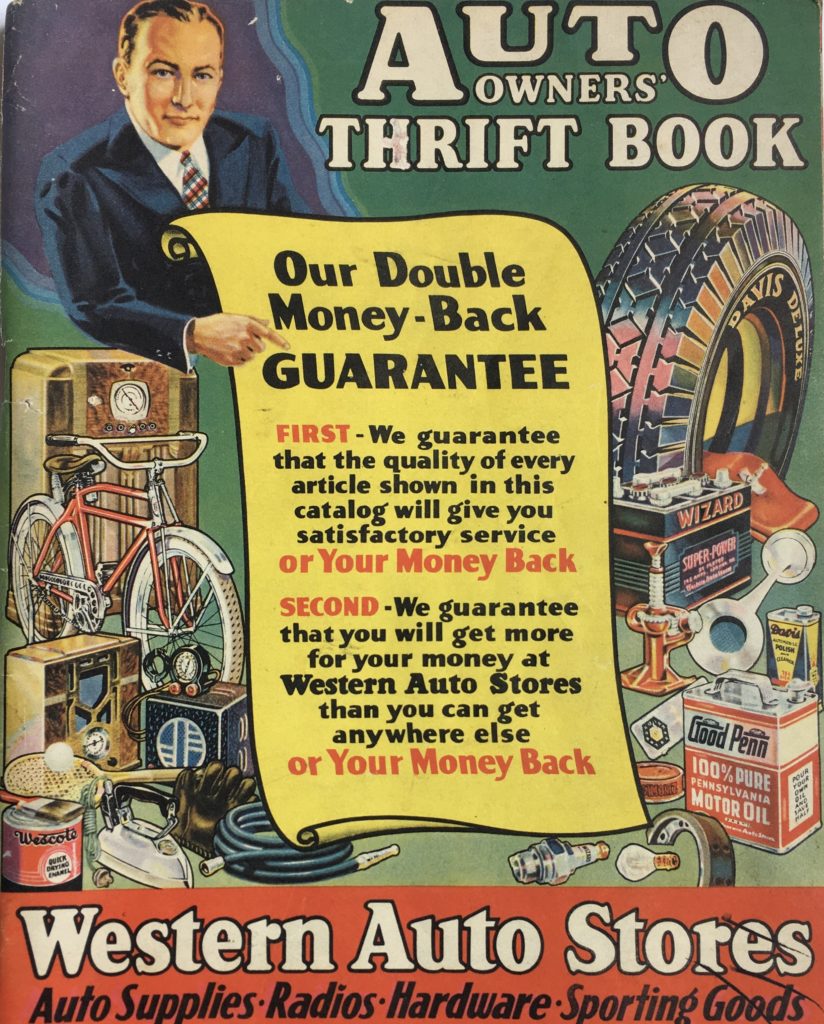

I practically grew up in my daddy’s small-town Western Auto store. Just like the kid whose daddy had a jewelry store about three doors away, or the one whose old man had a clothing store across the alley, or the one whose mother had a grocery store next door, or the two boys and girl whose daddy had a variety store on the other side of the grocery store.

I practically grew up in my daddy’s small-town Western Auto store. Just like the kid whose daddy had a jewelry store about three doors away, or the one whose old man had a clothing store across the alley, or the one whose mother had a grocery store next door, or the two boys and girl whose daddy had a variety store on the other side of the grocery store.

I played baseball with the clothing-store kid in Little League and after. I played basketball with the grocery-store kid in high school. I roomed for a while in college with one of the variety-store kids—one of the boys, not the girl. And I spent a lot of time with the jewelry-store kid using sledgehammers and chisels trying to break into the back of an ancient and immovable (at least for a couple skinny boys) safe that someone had dumped into the tall weeds behind his daddy’s store years before. When we finally got into it and realized that the ground hid the fact that it had no door and we could have just tunneled into it, all we found there was a bunch of rusty tin cans. That may have been the day we both first tried out a whole string of the cuss words we too often heard adults use when their expectations got squashed.

All of that playing was fine. It was playing around septic tanks that got me in trouble. All of the stores stayed open late on Saturday evenings, and one time around dusk when I was nine or ten or so, the grocery-store kid, the variety-store boys, and I were playing some sort of hide-and-seek or rock-chunking game, I don’t remember which, around several big, black, automobile-size septic tanks lying on their sides next to one of several tin-covered warehouses behind the stores. The tanks—similar to the more modern ones pictured here but larger—belonged to my daddy, who had a sideline of building supplies, and he told me not to play around back there when it started getting dark. I’m not sure why exactly. I guess he figured it wasn’t safe for some reason.

All of that playing was fine. It was playing around septic tanks that got me in trouble. All of the stores stayed open late on Saturday evenings, and one time around dusk when I was nine or ten or so, the grocery-store kid, the variety-store boys, and I were playing some sort of hide-and-seek or rock-chunking game, I don’t remember which, around several big, black, automobile-size septic tanks lying on their sides next to one of several tin-covered warehouses behind the stores. The tanks—similar to the more modern ones pictured here but larger—belonged to my daddy, who had a sideline of building supplies, and he told me not to play around back there when it started getting dark. I’m not sure why exactly. I guess he figured it wasn’t safe for some reason.

If so, he was right. At one point when I was either running from one of the other boys or trying to get away from the rocks they were chunking, I ducked down behind one of the septic tanks to hide, landed on my hands and knees, and rammed the heel of my right hand onto the jagged edge of a broken Coca-Cola bottle, just below the thumb. Blood gushed out of an equally jagged, inch-long gash, and one of the boys ran to get Daddy. I’m not sure if I was worried right then more about the blood or more about a likely tongue-lashing or something worse.

Fortunately, the town’s only doctor had an office half a block away and he kept late hours too. I can still see him cleaning out the wound and stitching it up. In fact, I can almost still feel it.

The appropriate ending for this true story might be for me to say that afterward when my daddy told me not to do something, I always paid more attention. But if I told you that, I’d be lying.

To be notified of new posts, please email me.