“When Lawmakers Howled Like Dogs,” or “The Day They Shut Down Louisiana,” or “Closed” would each also be as appropriate a title for this post as “Throw Me Some of Them Goobers.” All four of them are real aspects of a 1986 episode that the current national health and economic crisis has brought back to mind for me. And I can’t help wondering if it has also done that for at least a few others who experienced it.

“When Lawmakers Howled Like Dogs,” or “The Day They Shut Down Louisiana,” or “Closed” would each also be as appropriate a title for this post as “Throw Me Some of Them Goobers.” All four of them are real aspects of a 1986 episode that the current national health and economic crisis has brought back to mind for me. And I can’t help wondering if it has also done that for at least a few others who experienced it.

What happened then seemed at the time about as serious as anything could be. Even so, in addition to being greatly concerning and highly irritating, some aspects of it appeared almost comical in a head-shaking sort of way. From the perspective of today’s health threats and institutional closings, the 1986 episode pales all around, and there doesn’t seem to be anything remotely amusing about what’s happening now. But there definitely are parallels of disbelief, emotional shock, job loss, political maneuvering, media feeding, and flailing about for solutions.

For me, it all started one Thursday in early June with a 6:00 a.m. phone call from a member of the board of the Louisiana State Museum asking, “Have you seen the newspaper this morning? You are being zeroed out of the state budget.”

At the time I was director of the Louisiana State Museum system, headquartered in New Orleans with multiple sites in the French Quarter, including a former U.S. Mint and two 1790s buildings—one of which, the Cabildo, had hosted the signing of the Louisiana Purchase agreement—plus the former state capitol building in Baton Rouge and an exhibit center on the state fairgrounds in Shreveport. I had been in the position for only four months and was living in a Crescent City studio apartment while my wife remained in Buffalo, New York, trying to sell our house there. To say the least, this wasn’t a message I was prepared to hear.

It also made me feel a little stupid for having taken a sub-cabinet-level position in state government—I was one of five assistant secretaries of the Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism—while the governor, Edwin Edwards, was under federal indictment for mail fraud, obstruction of justice, and bribery. “There’s nothing to it, he’s innocent, and it’ll all be over before you start the job,” the board had assured me. A new position closer to my hometown in southern Arkansas with more responsibility and a higher salary had proved too tempting.

Ever the schemer, Edwards, who wanted to legalize gambling—ostensibly to increase tax revenues at a time of declining oil prices, a huge factor in Louisiana life—had sent the legislature a budget that was $437 million in the red. The house of representatives, which didn’t want to raise taxes but had never overridden any governor’s budget, had accepted it as submitted and sent it on to the senate. Inasmuch as the legislature could not pass a deficit budget, the senate finance committee had balanced it late the night before my phone call by cutting all funding for the state museum system, state parks system, and state library, as well as half of the funding for Charity Hospital in New Orleans, the largest medical facility in the state.

The governor and the senators appeared to think that this would create enough public outrage that the house of representatives would go along with revenue increases, the cuts could be restored, and the budget could be finalized before the legislative session ended. Meanwhile, hundreds of state employees faced the loss of their jobs, untold numbers of Louisiana residents faced reduced medical services, and the state’s tourism industry seem poised to grind almost to a halt, threatening even more jobs.

My colleagues in charge of the state’s park, library, and other cultural and tourism activities, hundreds of private stakeholders, and I immediately began trying to persuade the legislators to close the funding gap. We also began doing everything we could think of to rally public support.

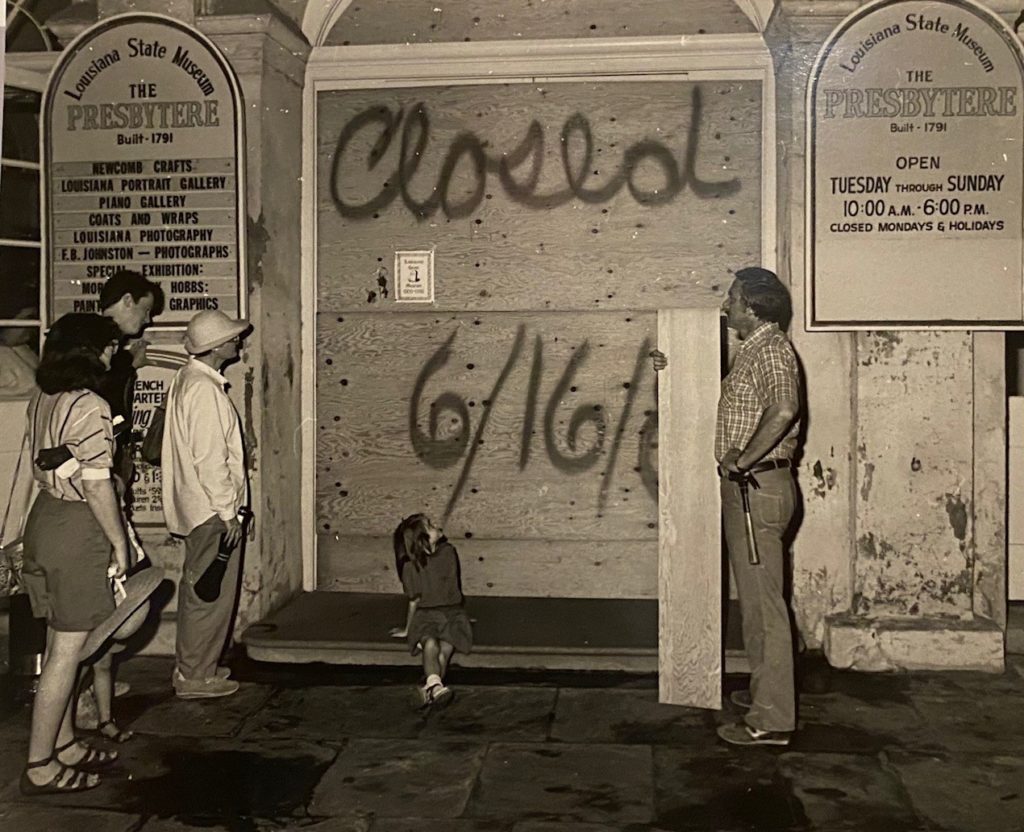

A few hours after that early morning phone call, museum staff boarded up the entrance to one of the near-identical 1790s buildings flanking St. Louis Cathedral on Jackson Square, the most photographed site in the state. The next day, following an emergency late-morning museum board meeting, two members and I did simultaneous live TV interviews with the media out front on the street.

That weekend, multiple newspapers across the state carried photographs of the boarded-up building under headlines like “The Day They Shut Down Louisiana” and “A Legislative Game of Chicken,” and on Monday, we bussed supporters to Baton Rouge to demonstrate. They managed to get inside the capitol building, but only after security personnel confiscated all of their clever placards and signs. The following day, before a previously scheduled and much publicized evening reopening of a newly restored historic house in the French Quarter, we decorated the 18th-century home in black bunting to signify mourning and generate even more media stories.

In the following days, despite its being against the law, the state parks director and I went onto the floor of both houses of the legislature to buttonhole members. No one tried to stop us, and while some took us seriously, others didn’t. I will never forget sitting against the back wall in the senate chamber and watching senators, who were sharing roasted peanuts from paper bags, call out to colleagues, “Throw me some of them goobers.” Or sitting in the back of the house chamber listening to representatives, who were considering a special tax on pet food, howl in unison like dogs each time the bill came up for a reading. There were times I thought I might as well have been trying to talk to one of the mules from the mock jazz funeral we did in the French Quarter to publicize a documentary film we helped make.

In the following days, despite its being against the law, the state parks director and I went onto the floor of both houses of the legislature to buttonhole members. No one tried to stop us, and while some took us seriously, others didn’t. I will never forget sitting against the back wall in the senate chamber and watching senators, who were sharing roasted peanuts from paper bags, call out to colleagues, “Throw me some of them goobers.” Or sitting in the back of the house chamber listening to representatives, who were considering a special tax on pet food, howl in unison like dogs each time the bill came up for a reading. There were times I thought I might as well have been trying to talk to one of the mules from the mock jazz funeral we did in the French Quarter to publicize a documentary film we helped make.

Before the end of the session, the legislature restored about two-thirds of the funding cuts, but the museum was still forced to lay off 53 employees in order to stay open, and the parks system had to close several areas. Some months later, the legislature went into special session to consider various new tax measures, but the parks director and I didn’t get a chance to repeat our on-site lobbying efforts. By that time, the Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism had been placed under the direction of the lieutenant governor, and he sent the two of us on a statewide media tour to keep us out of trouble, and maybe out of the pokey.

This second round of push, pull, and tug resulted in the restoration of half of the remaining lost funding and the restoration of some but not all jobs. Looking back and remembering the full episode gives me all the more empathy for what so many people are going through today in a much more heightened and traumatic way. It does little however, to dispel the notion that however much we may prefer it over potential alternatives, the democratic process is often a messy affair.

To be notified of new posts, please email me.