Here we go again. The U.S. Supreme Court recently heard oral arguments in another critical case that could be decided by an originalist interpretation of the Constitution. The Court’s ruling, expected sometime in June, could change the way we elect future presidents.

Here we go again. The U.S. Supreme Court recently heard oral arguments in another critical case that could be decided by an originalist interpretation of the Constitution. The Court’s ruling, expected sometime in June, could change the way we elect future presidents.

According to some legal scholars and Court observers, the case—Moore v. Harper—hinges in significant part on the meaning of “Legislature” in Article I, Section 4, Clause 1 (the Elections Clause) and in Article II (the Executive Power Article), Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution.

The relevant wording in Article I is: “The Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations….”

The relevant wording in Article II is: “Each state shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled to in the Congress….” Elsewhere in Article II and in the 12th Amendment, the Constitution provides for those electors to meet in their respective states and cast ballots for president and vice president.

How the Supreme Court ultimately defines “Legislature” could drastically alter presidential elections.

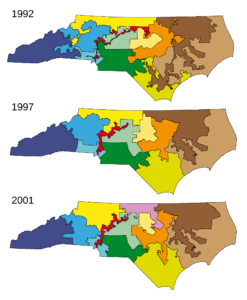

Moore v. Harper arises from the practice of gerrymandering, whereby the majority party in state legislatures routinely redraw the boundaries of congressional districts in their respective states every 10 years, following each census, to ensure that party’s control of as many districts, and therefore as many electors, as possible.

In this latest of several gerrymandering-related cases to reach the Court, Common Cause member Rebecca Harper is one among many citizens who have been challenging gerrymandering in North Carolina for several years. [The illustration shows NC congressional districts from 1992 to 2001.] Apparently, Harper’s name is attached to this case only as a result of her involvement in earlier cases that evolved into this one; she doesn’t know the exact reason herself. Timothy K. Moore is the Speaker of that state’s Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

In this latest of several gerrymandering-related cases to reach the Court, Common Cause member Rebecca Harper is one among many citizens who have been challenging gerrymandering in North Carolina for several years. [The illustration shows NC congressional districts from 1992 to 2001.] Apparently, Harper’s name is attached to this case only as a result of her involvement in earlier cases that evolved into this one; she doesn’t know the exact reason herself. Timothy K. Moore is the Speaker of that state’s Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

In Moore v Harper, the GOP-dominated North Carolina House is appealing a ruling by that state’s supreme court striking down a gerrymandered congressional map that would have ensured Republican control of 10 of the state’s 14 districts.

Moore asserts that the state court lacked authority for such a ruling. This contention rests upon the dubious and dangerous legal proposition known as “the independent state legislature theory,” or ISL.

ISL holds that where federal elections are concerned—whether in regard to drawing congressional district lines or to determining who can cast ballots, as well as where and when—only the state legislatures themselves can set the rules, even to the extent of ignoring rules of judicial review set in state constitutions.

The independent state legislative theory is hotly debated, but the majority of constitutional scholars and other legal experts reject it. Those who defend it do so on “originalist” grounds. That is that the term “Legislature” means exactly and only what it appears to mean in the relevant constitutional language: state legislative bodies. Even so, a number of originalist scholars have filed amicus briefs against ISL in Moore v. Harper because of its potential harm to our democracy.

Carried to its extreme, ISL could mean ultimately that the majority in any state legislature could choose that state’s presidential electors regardless of whom anyone else in the state—a majority of individual voters included—might prefer. In other words, state legislatures, not the people, could choose the president and vice president.

After the Supreme Court arguments, journalist Amy Davidson Sorkin, writing for the New Yorker, called the Harper v. Moore case “muddled.” That seems almost an understatement.

Over the course of three hours on December 7, 2022, lawyers and justices discussed previous instances around the country where state governors or state courts had overruled elected state legislatures in matters related to redistricting. Central to that discourse was whether the constitutions of those states allowed such actions.

Over the course of three hours on December 7, 2022, lawyers and justices discussed previous instances around the country where state governors or state courts had overruled elected state legislatures in matters related to redistricting. Central to that discourse was whether the constitutions of those states allowed such actions.

Discussants argued over whether a state court or a governor overriding a state legislative body under authority of that state’s constitution was, in a sense, legislating, and therefore in such an instance, fell within the meaning of “Legislature” in the U.S. Constitution as it applied to federal elections.

The U.S. Supreme Court has never relied on independent state legislative theory to determine the outcome of a case. On the contrary, in 2015 the Court specifically rejected ISL in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. In doing so, the Court relied on a broad, rather than narrow, definition of the word “Legislature” in the Constitution.

Three years earlier, after Arizona voters approved an independent commission to redraw congressional districts, the state legislature, desiring to retain that power solely for itself, sued on the grounds that the referendum violated the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The U.S. District Court for Arizona rejected the suit on the grounds that the word “Legislature” in the Elections Clause refers to the “process” that a state uses, under authority of its own constitution, to make laws. The district court pointed out that the Arizona constitution allowed for lawmaking through voter initiative.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the district court’s ruling by a vote of 5-4, with current justices Roberts, Thomas, and Alito dissenting. The majority opinion for that case citied two previous cases, Ohio ex rel. Davis v. Hildebrant (1916) and Smiley v. Holm (1932), both of which affirmed that redistricting is a legislative function performed in accordance with a state’s particular processes for lawmaking, which may include a referendum or a governor’s veto.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the district court’s ruling by a vote of 5-4, with current justices Roberts, Thomas, and Alito dissenting. The majority opinion for that case citied two previous cases, Ohio ex rel. Davis v. Hildebrant (1916) and Smiley v. Holm (1932), both of which affirmed that redistricting is a legislative function performed in accordance with a state’s particular processes for lawmaking, which may include a referendum or a governor’s veto.

At one point during the Moore v. Harper oral arguments, the Harper lawyer pointed out that in the 233 years since the U.S. Constitution went into effect, states have never read the Elections Clause in a way that proponents of the independent state legislative theory do. He said doing so would create a confusing two-track elections system with one set of rules for federal elections and another for state elections. Thus, he continued, case after case of disputes would wind up before the U.S. Supreme Court, creating chaos.

That argument led to a lengthy discussion regarding the relevant roles of state and federal courts in a variety of questions related to federal elections. Justices Alito and Thomas pondered whether redistricting was a political matter rather than a justiciable matter and therefore not something that should concern the U.S. Supreme Court. The Harper lawyer pointed to Baker v. Carr (1962) and reminded the Court that in response to a previous lawsuit in Tennessee, it had already held that redistricting is justiciable under the 14th Amendment.

However, further discussion brought up Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), also from North Carolina. In that instance, for purposes of issuing a decision, the Supreme Court pared a North Carolina case with Benisek v. Lamore, a gerrymandering dispute from Maryland. Following a 5-4 vote, the Court ruled that “partisan gerrymandering claims present questions beyond the reach of federal courts” and so dismissed the cases for lack of jurisdiction. Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion, joined by Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh.

The oral arguments in Moore v. Harper also included other relevant points of law and interpretation I’ll not attempt to describe here. However, none of those diminish the key question of what “Legislature” means in Articles I and II of the Constitution.

The oral arguments in Moore v. Harper also included other relevant points of law and interpretation I’ll not attempt to describe here. However, none of those diminish the key question of what “Legislature” means in Articles I and II of the Constitution.

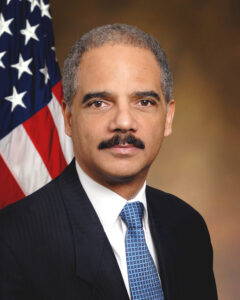

So, the brings me back to Sorkin’s characterization of the case as muddled. To whatever extent that is true, one thing seems certain. No matter how partisan observers may regard former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, it would be a serious misstate for anyone to discount his statement to the National Redistricting Foundation regarding the case. He wrote that if the Court upholds the independent state legislature theory put forth by Moore, “it would not only damage a cornerstone of our democracy, it could unleash a level of gerrymandering from both parties across the country that would do incalculable damage to our democracy.”

Most legal commentary I have heard or read suggests that at present the justices are divided into three camps on ISL. Predictably, Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch favor it, while Justices Sotomayor, Kegan, and Jackson reject it. Justices Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett seem to hold various views somewhere in the middle. For the sake of our nation, all Americans should hope that come June, at least two of those last three justices join the rejectors.

Sources for this blog include, among others, Wikipedia entries and websites of the following: ACLU, Charlotte Observer, Democracy Dockett, Justica, National Redistricting Foundation, SCOTUSBLog, The Guardian, and The New Yorker.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.