You may wonder why anyone would ask such a question. After all, we fought a war over slavery, and the 13th Amendment outlawed it.

You may wonder why anyone would ask such a question. After all, we fought a war over slavery, and the 13th Amendment outlawed it.

The question remains relevant and important today because scholars have long debated it. Activists have long locked horns over it. Politicians have long pontificated about it. And all of these are still going full-throat, as race-based issues of society, politics, and economics remain unresolved and divisive.

Many also still argue about whether Abraham Lincoln was at heart proslavery or antislavery. The two questions go hand in hand, and a new book about Lincoln calls attention to both again. The question about the Constitution is the most fundamental. But Lincoln’s views hinged in large part on it. And it comes up repeatedly in current back-and-forth talk and finger-pointing about racism and antiracism.

The new book is The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution by James Oakes, Humanities Chair and Distinguished Professor of History, American Studies, and Africana Studies at the City University of New York Graduate Center. David W. Blight, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Frederick Douglass and Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, penned a long and thoughtful essay about it for a recent issue of the New York Review of Books.

The new book is The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution by James Oakes, Humanities Chair and Distinguished Professor of History, American Studies, and Africana Studies at the City University of New York Graduate Center. David W. Blight, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Frederick Douglass and Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, penned a long and thoughtful essay about it for a recent issue of the New York Review of Books.

Disagreement about slavery and the Constitution originated with the framers, and debate about their motives and actions followed close behind. The words “slavery,” “slave,” and “enslaved” do not appear in the Constitution, as adopted in 1787, or in the Bill of Rights, added in 1791. But in that original document and those first ten amendments to it, there are several features having to do with what proslavery forces in the 1830s and afterward called “the peculiar institution.”

The first is the so-called “Three-Fifths Compromise” (Article I, section 2, Clause 4), stating that for the purpose of determining representation in Congress and the Electoral College, a state’s population would be the total of “free Persons,” indentured servants, and “excluding Indians…three fifths of all other Persons.”

The second is a clause stating that Congress would not prohibit “the Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit” prior to 1808 (Article I, Section 1, Clause 1)—referring to the slave trade and allowing it to continue until that date.

Another is a clause requiring that escaped “person[s] held to Service or Labour” under a state law be returned to their owners in that state (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3)—the so-called “fugitive slave” provision. And then there is the 10th Amendment—the so-called “states’ rights” provision—proclaiming that any powers not specifically delegated to the United States or prohibited to the states “are reserved to the States respectively.”

Proslavery factions in the late 18th century saw all these provisions as supporting slavery, or the rights of states to maintain it. Individuals who argue today that the framers were proslavery see them similarly.

Antislavery factions in the late 18th century and individuals who hold today that the framers were not proslavery point to a different group of provisions. One of these is the 4th Amendment, which protected people from “unreasonable searches and seizures” and could be interpreted as applying to fugitive slaves. Another was the 5th Amendment provision that “No person shall…be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without the due process of law.” In pointing to this provision, the antislavery argument ignored the word “property.”

In addition, antislavery factions highlighted every place in the Constitution, including the Bill of Rights, that projected any sort of spirit of natural rights and egalitarianism.

So, how did it happen that the Constitution was written in such a way that both camps could find support for their particular positions in it?

Over the years, the most widely accepted and widely taught explanation has been, in a word, “compromise.” Here’s how the Bill of Rights Institute describes it currently in a curriculum package for teachers and schools: “The framers made a prudential compromise with slavery because they sought to achieve their highest goal of a stronger Union of republican self-government. Since some slaveholding delegations threatened to walk out of the Constitution if slavery was threatened, there was a real possibility that there would have been separate free and slave confederacies instead of the United States. The free states would have lost all leverage over the slave states to end slavery if they had separated. The Framers had to create the Union with the institution of slavery but built a regime of liberty that they hoped would lead to slavery’s ultimate extinction.”

Over the years, the most widely accepted and widely taught explanation has been, in a word, “compromise.” Here’s how the Bill of Rights Institute describes it currently in a curriculum package for teachers and schools: “The framers made a prudential compromise with slavery because they sought to achieve their highest goal of a stronger Union of republican self-government. Since some slaveholding delegations threatened to walk out of the Constitution if slavery was threatened, there was a real possibility that there would have been separate free and slave confederacies instead of the United States. The free states would have lost all leverage over the slave states to end slavery if they had separated. The Framers had to create the Union with the institution of slavery but built a regime of liberty that they hoped would lead to slavery’s ultimate extinction.”

It’s useful to know that the Bill of Rights Institute was founded by the ultra-conservative Koch brothers and is funded chiefly by private foundations that support right and center-right public-policy organizations. There is, however, an abundance of academic scholarship that underpins this interpretation in varying ways and degrees too numerous and involved to go into here.

The most widely held counter view, and one that has been gaining new traction in recent years, is that, on the whole, the framers were proslavery, or at least not opposed to it. Adherents to this interpretation point out that the majority of Constitutional Convention delegates who signed the completed document either owned slaves or were profiting somehow from slavery.

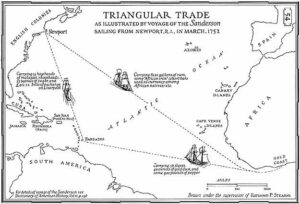

These adherents also point out that northern states benefitted economically from slavery as much as southern states. The New England textile industry depended on southern cotton. Rhode Island played a major role in the triangular slave trade that brought enslaved Africans to America. And financiers, banks, insurers, shipbuilders, and others in New York did business with slave traders and slave owners.

These adherents also point out that northern states benefitted economically from slavery as much as southern states. The New England textile industry depended on southern cotton. Rhode Island played a major role in the triangular slave trade that brought enslaved Africans to America. And financiers, banks, insurers, shipbuilders, and others in New York did business with slave traders and slave owners.

Never mind, say scholars and activists who contend that the Constitution was proslavery, that Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Adams, and others made various statements about the immorality of slavery. Few delegates who owned slaves freed them, and in the end, the framers adopted a Constitution that perpetuated slavery.

These conflicting views of the Constitution were disputed even more energetically prior to the Civil War. Activists like temperance crusader and abolitionist William Goodell—who ran for president in 1852 on the Liberty Party ticket—and eventually even Frederick Douglass considered the Constitution antislavery.

These conflicting views of the Constitution were disputed even more energetically prior to the Civil War. Activists like temperance crusader and abolitionist William Goodell—who ran for president in 1852 on the Liberty Party ticket—and eventually even Frederick Douglass considered the Constitution antislavery.

Douglass, focusing on the preamble to the Constitution, put it this way in a speech in Scotland in 1860. The “language” of the preamble, he said, is “‘we the people’; not we the white people, not even we the citizens, not we the privileged class, not we the high, not we the low, but we the people, not we the horses, sheep, and swine…but…we the human inhabitants; and if Negroes are people, they are included in the benefits for which the Constitution of America was ordained and established.”

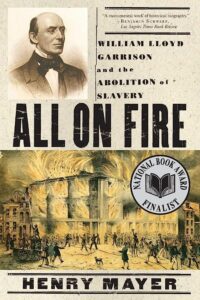

In contrast, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called the Constitution “a covenant with death” and an “agreement with hell.” It was Garrison that Bernie Sanders echoed at Liberty University in 2015, when he riled listeners by saying that the United States “in many ways was created” as a nation “from way back on racist principles.”

In contrast, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called the Constitution “a covenant with death” and an “agreement with hell.” It was Garrison that Bernie Sanders echoed at Liberty University in 2015, when he riled listeners by saying that the United States “in many ways was created” as a nation “from way back on racist principles.”

So, bottom line, there has never been broad agreement on whether the Constitution was proslavery or antislavery. Nor, it seems reasonable to conclude, will there be any time soon.

But what about Lincoln? Scholars are still debating what he believed and when he believed it. The esteemed historian Eric Foner is among those who have thought that Lincoln, even while disliking slavery, evolved gradually into opposing it. According to Blight, Oakes falls into that camp as well, presenting Lincoln as a gradualist who, in his first inaugural address endorsed citizenship for free Blacks, but who, even as he moved on to the Emancipation Proclamation and tactics that helped ensure the 13th Amendment, didn’t think the country would ever adopt true racial equality.

And here we are today, more than a century and a half later, with that ideal still eluding the country. “Oh,” many say, “but we have made progress.” I doubt that anyone who is a victim of racial discrimination finds that satisfactory.

Sources for this post include: Slavery and the Constitution Lesson, Liberty and Equality Unit, Bill of Rights Institute; Ian J. Aebel, “Was the Constitution of 1789 Anti-Slavery or Pro-Slavery?” History News Network website; David W. Blight, “Two Constitutions,” New York Review of Books, June 8, 2023; Timothy Sandfeur, “The Anti-Slavery Constitution,” National Review, September 30, 2019; David Waldstriecher, “How the Constitution Was Indeed Pro-Slavery,” The Atlantic, September 19, 2015; and Gordon S. Wood, “Was the Constitution a Pro-Slavery Document,” The New York Times, January 12, 2021. Note: Spelling in blogs on this website follow the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

George Rollie Adams is a historian, educator, and award-winning author of South of Little Rock, Found in Pieces, and Look Unto the Land—authentic and compelling novels about small town race relations in the Jim Crow and Civil Rights-era South, available here.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.