Have you ever stood in line at an airport carousel trying to spot your luggage and thought about how most bags look alike? Or silently swore because this sameness makes your bag hard to spot? Have you ever wondered what’s in the bags that don’t look like most of the others?

Or, have you ever thought about how much the look of suitcases has changed over the years, yet the shape and average size have remained pretty much the same because we have to carry them and baggage-handlers have to stack them? Well, maybe except maybe when they are chunking them into cargo holds.

Or, have you ever thought about how much the look of suitcases has changed over the years, yet the shape and average size have remained pretty much the same because we have to carry them and baggage-handlers have to stack them? Well, maybe except maybe when they are chunking them into cargo holds.

What do you do with suitcases and other pieces of luggage—including briefcases, computer bags, and kids’ backpacks—when they’re worn out? Do you automatically toss them? What about luggage you no longer use because you bought something new that is more fashionable or more convenient to use?

I confess I’ve struggled with all of these questions, and it’s because even when empty of physical stuff, a piece of luggage can hold memories that seem more important than anything it ever transported. And I’ve found that in some instances, the longer I hold onto one of these items, the more important both the memories and the item itself become.

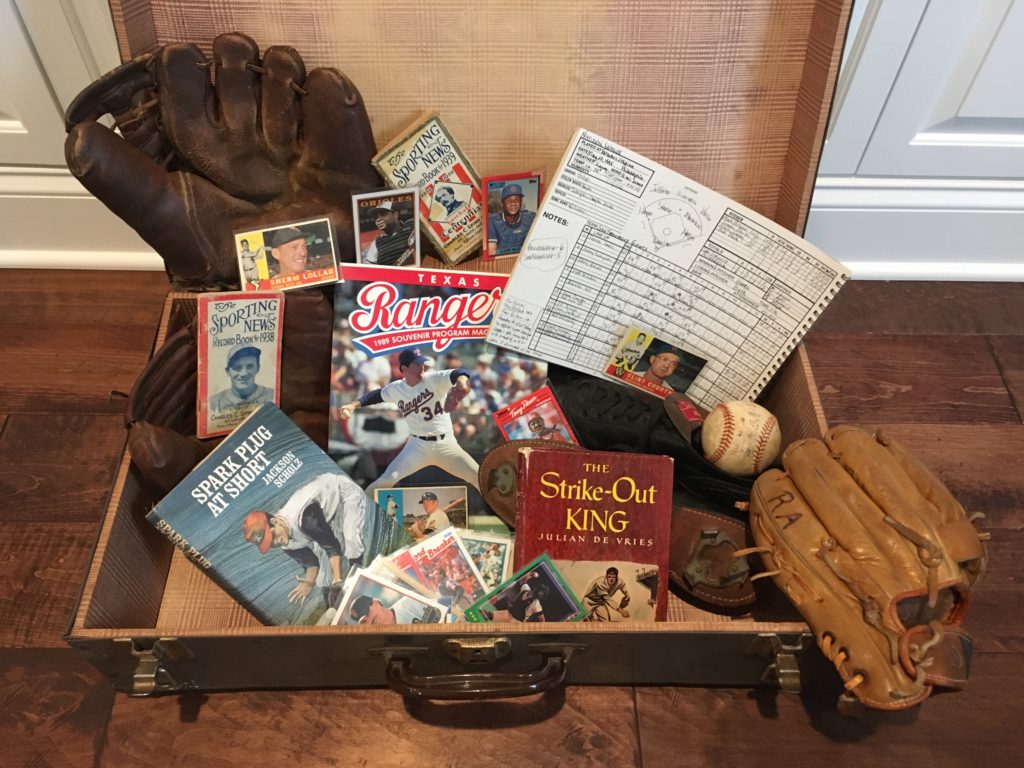

For instance, I still have a Samsonite suitcase I received as a high school graduation present. I can’t bring myself to get rid of it because it reminds me so much of that rite of passage and the sense of adventure I felt going off to college. Using it to store other memorabilia that I probably also don’t need but love just as much as the suitcase makes a good excuse for keeping it, however.

I also can’t get rid of the leather accordion-style briefcase I lugged all across the country when I worked for the American Association for State and Local History, even though it isn’t good for storing anything. When I look at it, but especially when I hold it, I can see in my mind’s eye not only some of the things I carried in it but also some of the interesting places I took it, like the Hearst Castle in California, home of one of the leading creators of so-called “yellow journalism” in the late 1800s; historic military installations such Fort Sam Houston in Texas and the Washington Navy Yard in the District of Columbia; and the stand-alone study on the site in Crawfordsville, Indiana, where General Lew Wallace wrote Ben Hur.

And I especially can’t part with an even older tin suitcase that my daddy carried when he took me on my first train-trip way more than half a century ago. We rode the trolley-like Doodlebug on the Rock Island Railroad from southern Arkansas to Little Rock then took an express to Memphis to attend a toy-buying show for Western Auto store owners. I use it now to hold still more stuff I can’t let go of.

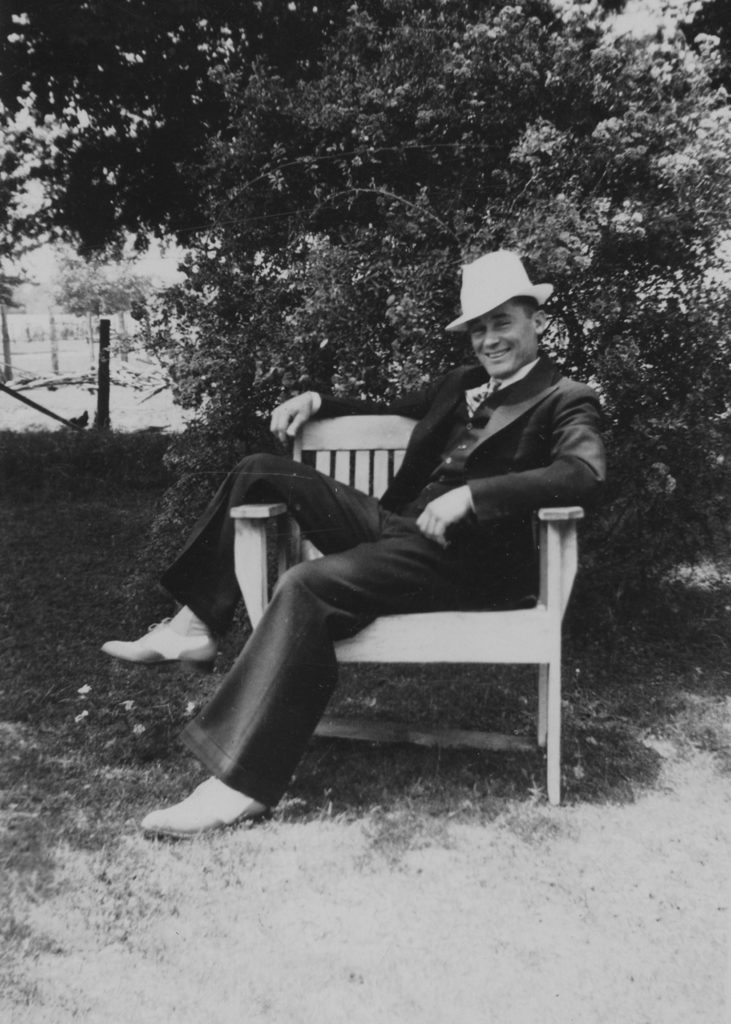

But mostly when I look at this suitcase, I see the man—pictured here before I was born—who along with my mother raised me. I see the café inside the Little Rock train station where we had lunch. I see the biggest array of toys I ever laid eyes on until I became president of the Strong National Museum of Play many years later. And I see the Peabody Hotel where we stayed and where every day we watched the famous Peabody ducks get off the elevator from their rooftop home and walk through the lobby to swim in the large fountain there, just as they still do—well, not the same ducks, of course.

Somehow, I feel I’m not alone in believing that when you really think about them, seemingly empty suitcases that have journeyed alongside us are not really empty, no matter whether we keep stuff in them or not.

To be notified of new posts, please email me.