Isn’t it strange how sometimes a series of small seemingly unrelated and not especially meaningful occurrences suddenly get pulled together by some other minor happening so that they add up to something bigger? A new insight, perhaps? Or the resurrection of a distant memory? Or renewed appreciation for something we already know?

Isn’t it strange how sometimes a series of small seemingly unrelated and not especially meaningful occurrences suddenly get pulled together by some other minor happening so that they add up to something bigger? A new insight, perhaps? Or the resurrection of a distant memory? Or renewed appreciation for something we already know?

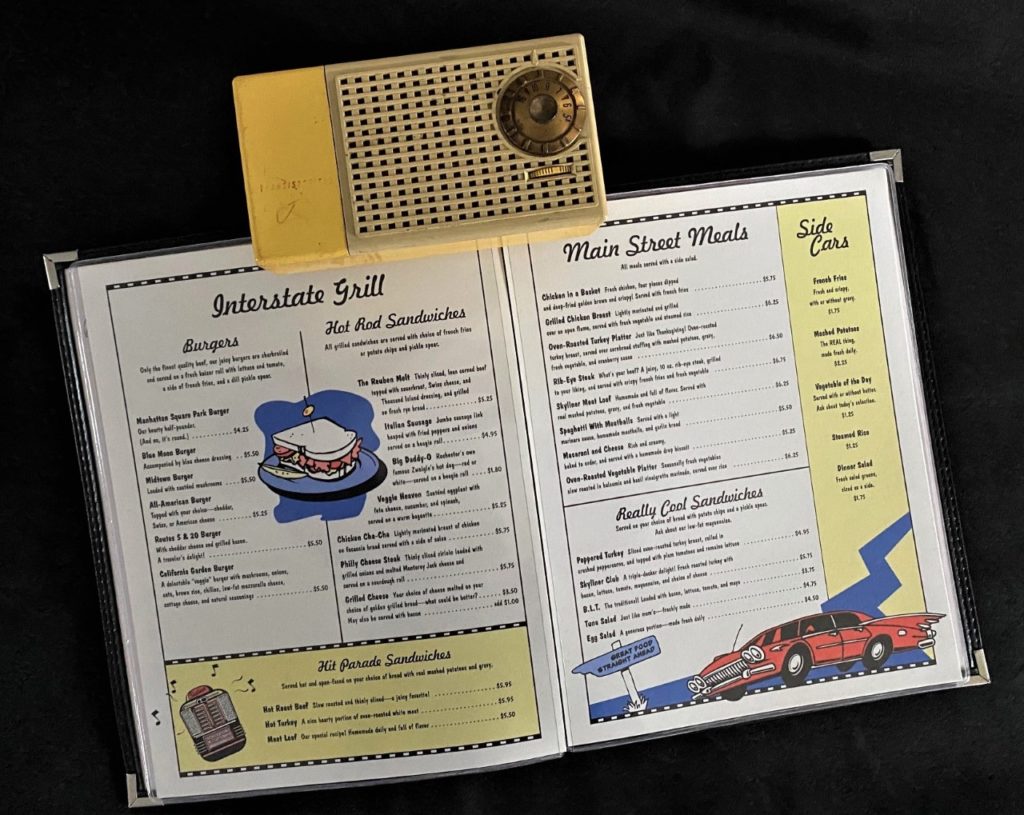

Not long ago, while looking for another thing from years past, I came across the menu from a 1950s-style diner. Not just any diner, but the Skyliner Diner that colleagues and I installed inside a specially constructed atrium at the Strong National Museum of Play back in 1997, before the museum assumed that name.

Looking through the menu took me back down all the roads, figurative as well as literal, that we traveled to acquire the diner, build a space for it, situate it, restore it, engage a food operator, determine the menu, and arrange for a table-top juke box system and select the tunes it could play. Lots of headaches, but also loads of fun.

When I came across the menu, I thought at the time about writing some sort of blog about all that. Then I set the idea aside as something that might be a nice stroll down memory lane for me but not interesting to anyone who didn’t work on the project.

When I came across the menu, I thought at the time about writing some sort of blog about all that. Then I set the idea aside as something that might be a nice stroll down memory lane for me but not interesting to anyone who didn’t work on the project.

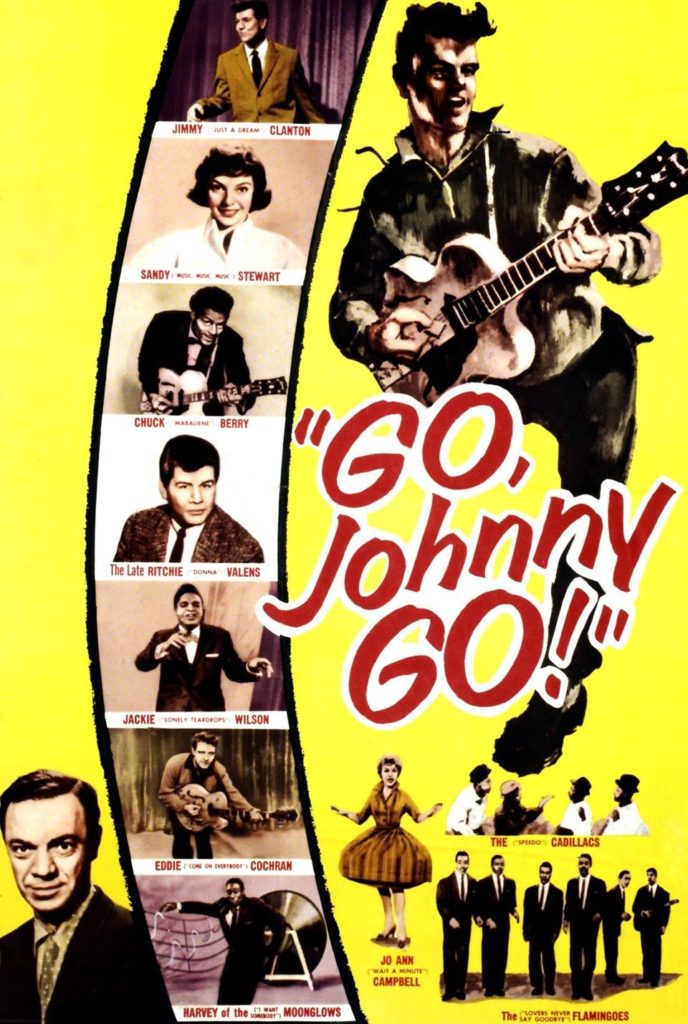

A little while later, as I was sitting down for an afternoon of watching March Madness, I happened upon a showing of the 1959 motion picture Go, Johnny, Go! I didn’t remember the movie, but I did remember Chuck Berry’s hit song “Johnny B. Goode,” which he sang during the opening credits.

Unfortunately, I also remembered how that talented and trailblazing artist tainted his legacy through income tax evasion, drug use, and behavior that led to multiple charges of physical and sexual abuse of women. I almost switched channels at that point, but I also remembered something else I’d recently read about Berry. More about that in a second. Meanwhile, other voices and images in the movie began to prevail.

Unfortunately, I also remembered how that talented and trailblazing artist tainted his legacy through income tax evasion, drug use, and behavior that led to multiple charges of physical and sexual abuse of women. I almost switched channels at that point, but I also remembered something else I’d recently read about Berry. More about that in a second. Meanwhile, other voices and images in the movie began to prevail.

As the film rolled, Jimmy Clanton, in the lead role of wannabe recording artist Johnny Melody, crooned “Angel Face,” Richie Valens belted out “Ohh My Head,” and Sandy Stewart sang “Mama, Can I Go Out?” It was Valens’ one and only motion picture appearance. He was killed in a plane crash with Buddy Holly and Jiles Perry Richardson (a.k.a. The Big Bopper, most famous for “Chantilly Lace”) in Iowa before the movie came out. At one point as I watched and listened, I glanced at my 1950s Raytheon transistor radio sitting on a nearby shelf, and a whole flood of 50s and 60s Rock ‘n’ Roll songs, movies, and artists paraded past.

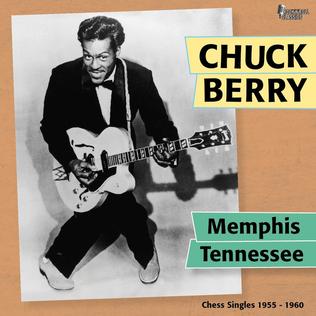

When, near the end of the film, Berry performed “Memphis, Tennessee,” no image of that city’s Sun Records recording studio popped into my head. But Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash—each of whom cut their first big hits there—all crowded into my vision. I was having my stroll-down-memory-lane moment, and more.

When, near the end of the film, Berry performed “Memphis, Tennessee,” no image of that city’s Sun Records recording studio popped into my head. But Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash—each of whom cut their first big hits there—all crowded into my vision. I was having my stroll-down-memory-lane moment, and more.

The songs and images also evoked something beyond nostalgia. They reminded me of the history of that era—the beginning of the Cold War and the start of the Civil Rights movement. And of how each generation of Americans experiences and remembers, both individually and collectively, its own unique view of the ever-shifting circumstances in the life of our country.

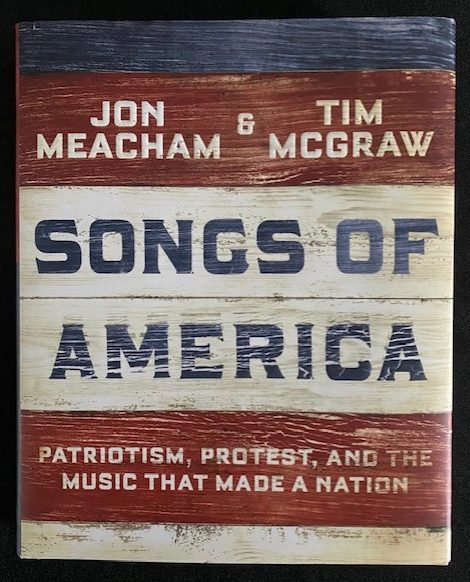

When the movie ended after about an hour, I continued to ignore March Madness, and this time I got up and walked over to the bookshelf. There I took down historian Jon Meacham’s and musician Tim McGraw’s Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation.

In the introduction, Meacham writes that history is neither a fairy tale nor a lullaby and that there has never been a “once upon a time” and will never be a “happily ever after” in America. But there has always been an effort “to ensure that hope can overcome fear, that light can triumph over darkness, and we can open our arms rather than clench our fists.” In eight concisely rendered chapters (Meacham) and informative sidebars (McGraw), the authors go on to describe and illustrate the ways that over time, from the Revolutionary era to the present century, music has lifted up and sustained Americans’ hopes and dreams for better, and has continued to remind us of those who struggled to bring light.

In the introduction, Meacham writes that history is neither a fairy tale nor a lullaby and that there has never been a “once upon a time” and will never be a “happily ever after” in America. But there has always been an effort “to ensure that hope can overcome fear, that light can triumph over darkness, and we can open our arms rather than clench our fists.” In eight concisely rendered chapters (Meacham) and informative sidebars (McGraw), the authors go on to describe and illustrate the ways that over time, from the Revolutionary era to the present century, music has lifted up and sustained Americans’ hopes and dreams for better, and has continued to remind us of those who struggled to bring light.

Meacham points out that Chuck Berry was one of those 50s and 60s Black artists—along with Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, and Curtis Mayfield, among others—whose songs appealed to white audiences by drawing upon certain white musical conventions and to Black audiences by including veiled civil rights messages. The best example, perhaps, is Sam Cooke’s “Change Is Gonna Come,” recorded by multiple artists over time. In “Johnny B. Goode,” Berry sang of overcoming white prejudice through the brilliance of musical talent. Despite Berry’s considerable personal faults, most of which came into view much later, “Johnny B. Goode” proved an influential song.

As I flipped through the pages of Meacham’s and McGraw’s book a second time, I thought about how all of us in America, from the beginning to the present, have been traveling in the same vessel and how now, as always, we have a collective responsibility to care for each other and work together to keep moving toward the light.

I left the book atop a stack of others on the coffee table in my study, with the intention of revisiting it yet again. Before I could do that, however, a writer friend sent me an invitation to attend a Zoom presentation being put on by the Community and Belonging Program of Nazareth College.

I left the book atop a stack of others on the coffee table in my study, with the intention of revisiting it yet again. Before I could do that, however, a writer friend sent me an invitation to attend a Zoom presentation being put on by the Community and Belonging Program of Nazareth College.

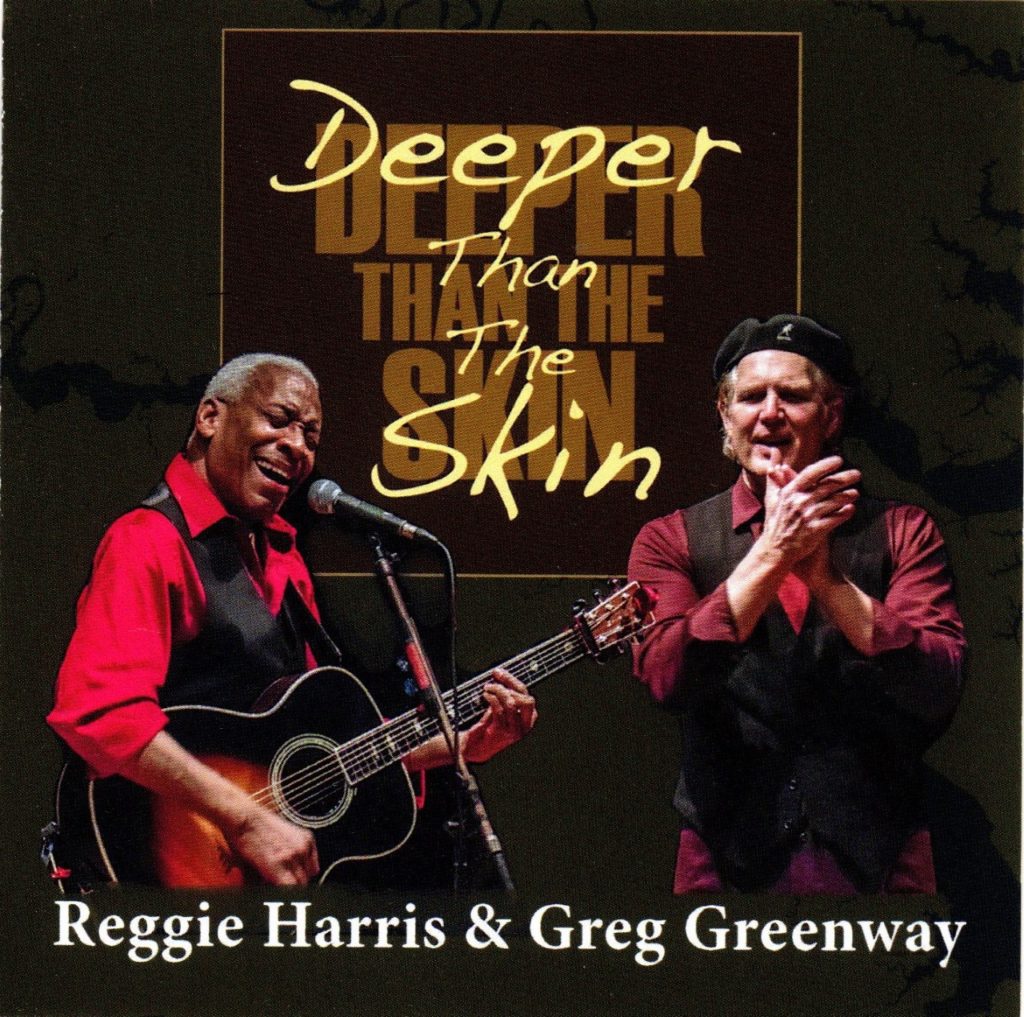

A few days later, I signed into the event and listened to Midwest-based musician and social activist Reggie Harris discuss “Music as a Historical Tool.” “We, as humans, are hard-wired for music and stories,” he began. For the next hour, in an engaging combination of talk and a cappella performance, he illustrated much of what Meacham and McGraw had written about—from the music of enslaved Americans to gospel to the protest songs of the 1960s. In closing, Harris stressed the importance of how “through songs we find connections to our hearts, and then to our minds, and then to each other.”

That was not the first time I had heard such a sentiment, or thought about it in one way or another, so I suppose it was not exactly a new insight. But it was a beautifully delivered culmination of the music-related memories I had been experiencing over the last several days. More importantly, it was a reminder, like Meacham’s and McGraw’s writing in Songs of America, of the importance of music in our history and our present-day lives. An admonition that we Americans have but one country. That it belongs to all of us. And that we all must work to ensure that all the good things it now offers, and can offer in the future, are equally and equitably available to each of us.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page. I can also be reached via Facebook.