Does the tremendous amount of hatred over the course of human history and across the world today ever become personally overwhelming even when it’s not aimed at you? And then you wonder anew—because you’ve thought about it many times before—how horrible it must be for those toward whom it’s directed?

These feelings struck me hard again recently because of two events and the way coincidence magnified them. So much so that I could not even walk my dog leisurely in the sunshine or sit down to a meal with family or friends without feeling guilty about having the freedom to enjoy such simple pleasures.

These feelings struck me hard again recently because of two events and the way coincidence magnified them. So much so that I could not even walk my dog leisurely in the sunshine or sit down to a meal with family or friends without feeling guilty about having the freedom to enjoy such simple pleasures.

The two events were: First, my reaching the final proofreading stages of a third novel dealing at least in part with hate, an occurrence important only to me; and second, the intensifying cruelty of Russia’s unjustifiable war against Ukraine, a happening that is jarring the world.

The coincidence was the arrival on my desk around this same time of three publications, each dealing in its own way with hate.

People often ask authors why they write certain stories, or why they write about certain topics, or why they write in general. I expect most write for multiple reasons, many of which they have in common with other writers. I also expect there are as many individual reasons as there are authors.

University of Virginia scholar Mark Edmundson names and discusses almost thirty broad reasons in his book Why Write: A Master Class on the Art of Writing and Why It Matters. Among those are to catch a dream, to earn a living, to find beauty and truth, to learn something, to remember, to stay sane, to have the last word, and to beat the clock. That last, he clarifies, is because writing is something one can do when “old”—I prefer the word “older”—and stay a little younger a little longer. I admit that’s true, but it’s also a reason I try not to dwell on.

University of Virginia scholar Mark Edmundson names and discusses almost thirty broad reasons in his book Why Write: A Master Class on the Art of Writing and Why It Matters. Among those are to catch a dream, to earn a living, to find beauty and truth, to learn something, to remember, to stay sane, to have the last word, and to beat the clock. That last, he clarifies, is because writing is something one can do when “old”—I prefer the word “older”—and stay a little younger a little longer. I admit that’s true, but it’s also a reason I try not to dwell on.

I write because I like doing it and because I want to try to tell stories that are both engaging and meaningful. And I want to shine additional light, within historical context, on the shamefulness of racial prejudice and injustice.

Naturally, I think about hatred when I write about prejudice and injustice. I also feel shame about them, as well as empathy and sorrow for all who endured them historically and all who endure them now.

Those are logical and normal feelings. But the three new publications arriving almost simultaneously pushed them to new levels for me.

The first publication was A Penitential Prayer: Poems on the Holocaust, by Gerald George, a former journalist and public history professional turned poet. The best way for me to explain how this outstanding work of literature work struck me is to share the review of it I posted on Amazon.

The first publication was A Penitential Prayer: Poems on the Holocaust, by Gerald George, a former journalist and public history professional turned poet. The best way for me to explain how this outstanding work of literature work struck me is to share the review of it I posted on Amazon.

“Gerald George tells us right up front that he wrote this book of poems as a kind of prayer of sorrow and penitence. And it is that. But it is also more. Everyone, especially in today’s world, should read this book, hold onto it, and read it again periodically, lest we as humans ever forget, even for a little while, the horrors of the Holocaust and what can happen when we let our guards down against the winds of prejudice and authoritarianism. George never states that sentiment directly, however. He doesn’t have to. His simple but beautifully rendered words and depictions let us experience in detail brief moments in the daily lives of both victims and perpetrators in ways that do not require interpretation. We see and know what they were doing and how they regarded it. We see and feel the cold disregard for human life. We see and feel the despair of millions. You can read histories of the Holocaust, and you can watch movies of the Holocaust, but I don’t believe any of those will touch your soul to the same degree that this book will.”

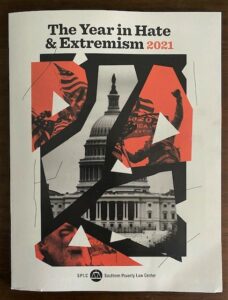

The second publication was The Year in Hate & Extremism, 2021, an annual report by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). The SPLC is dedicated to promoting racial justice and advancing the human rights of all people. Toward those ends, it tracks hate organizations and antigovernment organizations that espouse “a hierarchically ordered society in which certain groups of people hold more political, social, and economic power than others,” one that generally excludes “people of color, women, LGBTQ people, religious minorities, immigrants, and non-Christians.”

The second publication was The Year in Hate & Extremism, 2021, an annual report by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). The SPLC is dedicated to promoting racial justice and advancing the human rights of all people. Toward those ends, it tracks hate organizations and antigovernment organizations that espouse “a hierarchically ordered society in which certain groups of people hold more political, social, and economic power than others,” one that generally excludes “people of color, women, LGBTQ people, religious minorities, immigrants, and non-Christians.”

Examples of such hate and antigovernment organizations include the Ku Klux Klan, American Nazi Party, Aryan Freedom Network, American Freedom Party, United Skinhead Nation, Dixie Republic, American Immigration Reform Foundation, Americans for Truth about Homosexuality, ACT for America, Patriot Front, Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, John Birch Society, and all sorts of organizations with the words “militia” and “minutemen” in them.

The number of hate groups identified and tracked by SPLC is down from a historic high of 1,021 active organizations in 2018 to 733 in 2021, and the number of antigovernment groups is down from 566 in 2020 to 488 in 2021. But the 2021 total of 1,221 remains seriously alarming. More alarming still is how QAnon adherents are coalescing with such organizations, along with COVID conspiracy theorists, to recruit members openly and market their ideas through media to the general public.

The third publication was a double issue of the American Journal of Play, for which I had the honor and pleasure of being editor-in-chief at the time of its founding and during its first nine years. I had no role in the current volume devoted to Blackness and play, but I’m proud as heck of the team that did, led by Strong Museum historian Jeremy Saucier.

TheaAndrea M. Russworm, Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, guest-edited the volume and helped assemble the outstanding lineup of contributors to interviews and essays. As Saucier wrote in his introduction, the collection “challenges the field of play studies by offering new and important perspectives on play as a site for disruption, resistance, and joy in Black communities.” You can read the entire issue online from The Strong National Museum of Play.

TheaAndrea M. Russworm, Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, guest-edited the volume and helped assemble the outstanding lineup of contributors to interviews and essays. As Saucier wrote in his introduction, the collection “challenges the field of play studies by offering new and important perspectives on play as a site for disruption, resistance, and joy in Black communities.” You can read the entire issue online from The Strong National Museum of Play.

I agree with Saucier about what this double issue of the Journal means to the study of play, but it also reminded me of the role that hatred has played historically in depriving Black people in America not only of the kind of play opportunities that whites have enjoyed, but of all sorts of rights generally accorded to white people. Whatever justifications slaveowners may have come up with for enslaving other human beings, it is impossible to separate those motives from racism. And it is impossible to separate racism from hate, then or now.

The first article that caught my attention in the double issue was “The Play Practices of Enslaved Children,” by Shakeel Harris, a history PhD candidate at Louisiana State University. On the very first page, Harris shares the story of a five-year-old boy named Titus Bynes whose owners, in 1851, were training him to become a houseboy.

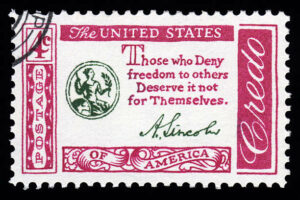

Bright and curious, young Titus saw them reading newspapers. Intrigued, he started sneaking looks at the pages. Soon he was copying letters of the alphabet from memory outside in the dirt with a stick. Eventually he began making words. When discovered, he was told that if he continued, his masters would cut off his arm. Imagine how frightening and devastating that must have been for him. You don’t need imagination to know how hateful and cruel it was.

Slaves were forbidden to learn to read and write lest it lead to rebellion. Even when one has read about that before, and about all the many other brutal aspects of slavery, Titus Bynes’ story is still heartbreaking. And, of course, it is only one among millions.

Slaves were forbidden to learn to read and write lest it lead to rebellion. Even when one has read about that before, and about all the many other brutal aspects of slavery, Titus Bynes’ story is still heartbreaking. And, of course, it is only one among millions.

If contemplating such hate-driven behavior makes me feel so badly, why do I read and write about it? Because it’s impossible to keep from wondering how some humans can treat other humans in such cruel ways. Because ignoring the pain and suffering that hate caused in the past is both insensitive and dangerous for the future of all of us. Because ignoring the pain and suffering that hate continues to cause is in itself cruel. And because confronting hate and those who harbor and act upon it is essential for preserving human decency and democratic society going forward.

George Rollie Adams is a historian, educator, and award-winning author of South of Little Rock, Found in Pieces, and Look Unto the Land—authentic and compelling novels about small town race relations in the Jim Crow and Civil-Rights-era South, available here.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.