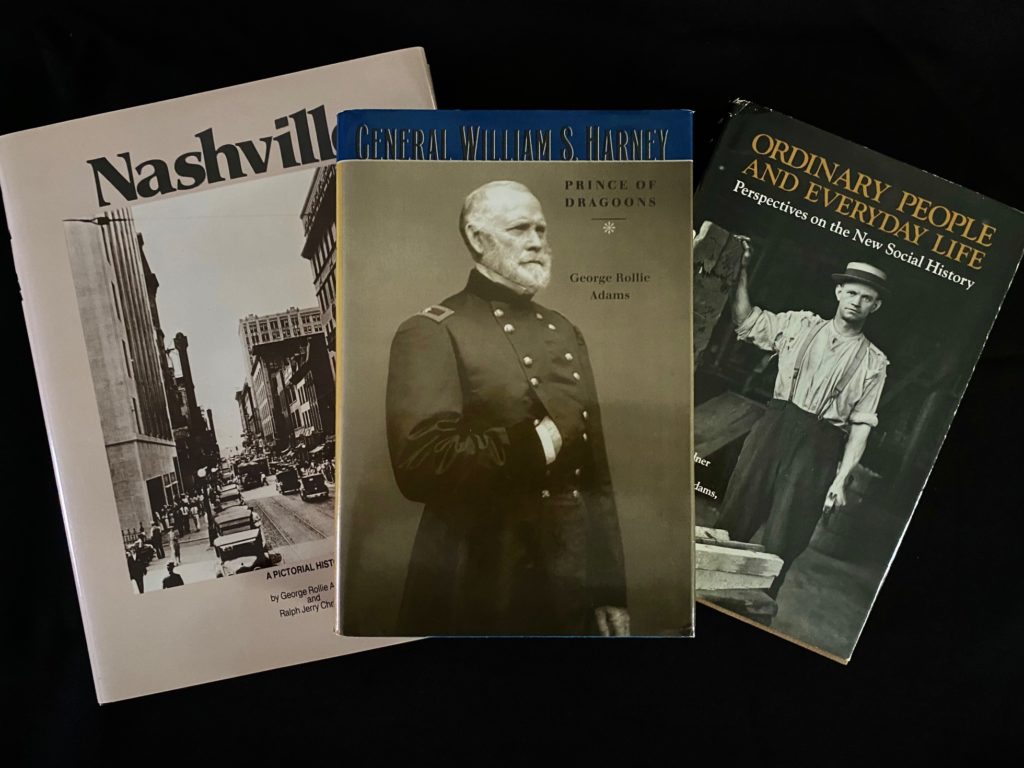

In late 2018, when the first edition of South of Little Rock was nearing publication, a friend asked why, after a career in history museums and historical writing and editing, I had taken up writing fiction. And why, he wanted to know, had I chosen initially to write fiction about discrimination and civil rights?

In late 2018, when the first edition of South of Little Rock was nearing publication, a friend asked why, after a career in history museums and historical writing and editing, I had taken up writing fiction. And why, he wanted to know, had I chosen initially to write fiction about discrimination and civil rights?

After we spoke, I put his questions and my response in a blog post. “The reason’s pretty simple,” I said. “It’s been decades since Brown v. Board of Education, since the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, and since a bunch of other court decisions and laws, and millions of people still face hatred and discrimination based on their skin color, their gender, their age, their sexual orientation, or their religion—or because they are perceived as some sort of threat to those who have different values and beliefs.”

Later, when I began to do readings and signings for South of Little Rock, I was often asked the same question. I always gave a version of that answer. Frequently, one or more attendees would then ask something on the order of, “That’s true, and it’s been going on for decades, even centuries. So, given its pervasiveness, and given that there have already been so many hundreds of books—novels and histories, plus political, sociological, and economic studies—written about it, what good do you think one more book is going to do?”

Among other things, my reply always included a version of what I wrote in the blog post, “If the story of how the imaginary citizens of the fictional town of Unionville . . . wrestle with issues of race and civil rights encourages even a handful more individuals to respect those who are different from them and to stand up against prejudice and its more dangerous form, bigotry, then the book will have been well worth the effort that went into it.”

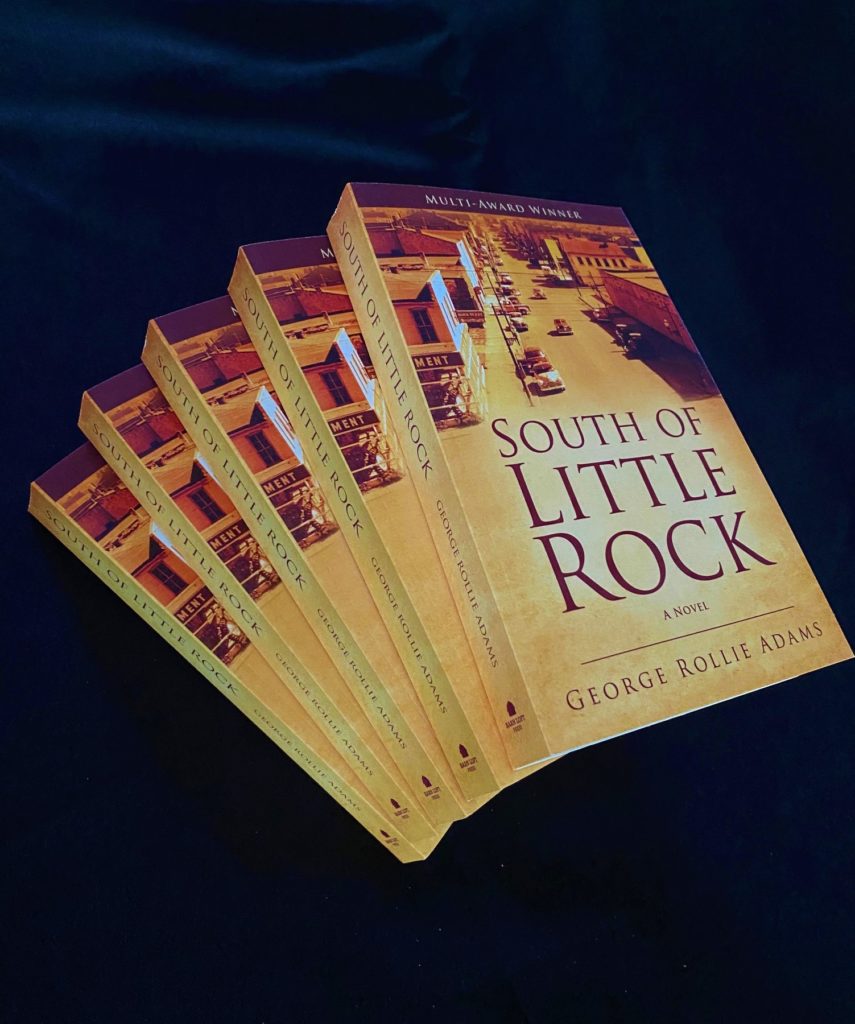

A year later, after South of Little Rock had received four independent publishing awards for regional and social issues fiction, I penned another blog post about why I wrote the book. In that post, I noted calls that historians and writers such as Suzanne W. Jones and Ralph Ellison had made for still more books dealing with prejudice, bigotry, and discrimination.

A year later, after South of Little Rock had received four independent publishing awards for regional and social issues fiction, I penned another blog post about why I wrote the book. In that post, I noted calls that historians and writers such as Suzanne W. Jones and Ralph Ellison had made for still more books dealing with prejudice, bigotry, and discrimination.

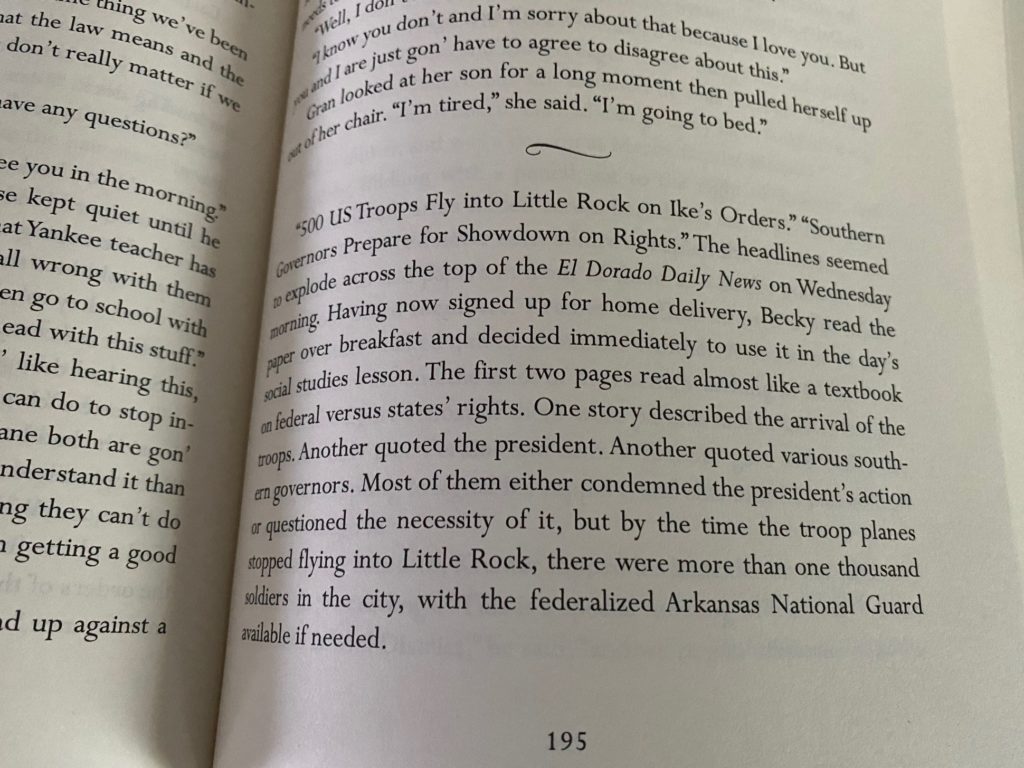

A host of writers from diverse backgrounds continue to write about these evils, and about not only the need to address them, but also about things each of us can do to help. Soon, I will be bringing out a second novel on racial discrimination in the South in the 1950s. Titled Found in Pieces, it is dedicated to the ideal of truth, honesty, and integrity in journalism and is relevant to today. As I worked on it over the last year, I hoped that in at least some small way, it, too, might help encourage change.

Anytime an author is about to bring out a new book, he or she is excited to see it in print, eager to make it available for people to read, hopeful that it will be well received, and anxious to see reviews. This time for me, however, that normal anticipation is dimmed by heightened sadness over the issues the book is intended to help resolve. The outpourings of racial hatred and of real-life stories of fear and despair currently playing out in lives, homes, streets, and seats of government across America highlight anew the enormity of the underlying issues and the task of overcoming them. These should distress every caring citizen.

Anytime an author is about to bring out a new book, he or she is excited to see it in print, eager to make it available for people to read, hopeful that it will be well received, and anxious to see reviews. This time for me, however, that normal anticipation is dimmed by heightened sadness over the issues the book is intended to help resolve. The outpourings of racial hatred and of real-life stories of fear and despair currently playing out in lives, homes, streets, and seats of government across America highlight anew the enormity of the underlying issues and the task of overcoming them. These should distress every caring citizen.

I am going ahead with the publication of Found in Pieces, but despite all the thought, work, and good intentions that have gone into it, and despite my hope that those who read it will find in it both enjoyment and inspiration, it seems to me at the moment less important than the efforts that so many tens of thousands of caring individuals are undertaking to make their cries for change heard by showing up, speaking up, and demonstrating in streets all across the country. They are doing so in spite of efforts by less-well-intended individuals to disrupt and discredit their efforts for their own various selfish and often hateful reasons. Those who are advocating for change deserve the admiration, thanks, and support of all Americans.

There are some encouraging signs that in this new round of nationwide calls for reform and greater social justice we will see additional progress. Let us hope that this time it will be neither incremental nor short-lived, but that it will be systemic and lasting.

To be notified of new posts, please email me.