If you were to ask your family and friends, or perfect strangers, what’s the best thing about the Christmas season, what would they say? Being with loved ones? Lights and decorations? Santa Claus? Christmas dinner? Celebrating religious traditions, Christian or other? Giving to others? Going to grandma’s house? Time away from school or work? Something else?

Personally, I find it difficult to single out one thing, but if pressed, I’d have to say memories—memories already made, and memories being made. Not to mention that memories involve most, if not all, of the foregoing.

Some Christmas memories posted recently on Facebook got me thinking about what Christmas was like in the small town, population about 1,500, where I grew up on the Arkansas-Louisiana border in the mid-1940s to mid-1950s. And how, in ways I did not then fully appreciate, my experiences were connected to other people and to the memories they were making at the same time.

During most of those years, the anticipation of Christmas began for me in July when my father began buying Christmas toys, including tricycles, bicycles, pedal cars, and wagons, for his Western Auto Associate Store (which later became the model for the OTASCO store in my novel South of Little Rock).

During most of those years, the anticipation of Christmas began for me in July when my father began buying Christmas toys, including tricycles, bicycles, pedal cars, and wagons, for his Western Auto Associate Store (which later became the model for the OTASCO store in my novel South of Little Rock).

A few times he went to a company trade show in Memphis, but mostly he ordered from a company catalog. Sometimes his only full-time employee assisted with the choosing. One summer when I was about ten, my father took me with him to Memphis, and I got to try out all sorts of display toys in the historic Peabody Hotel.

All of this, of course, was before shopping malls, K-Mart, Walmart, and Toys R Us. Our Western Auto store was the primary toy buying destination for families from miles around. In those days, most people didn’t drive great distances to shop in a larger town if they could get what they wanted locally.

Sometime each fall, Christmas merchandise would start arriving, and it was time to begin displaying things, which required assembling bicycles and wagons. I helped with that, and later my younger brother did too. We both clerked in the store, too, year-round, as early as about age twelve.

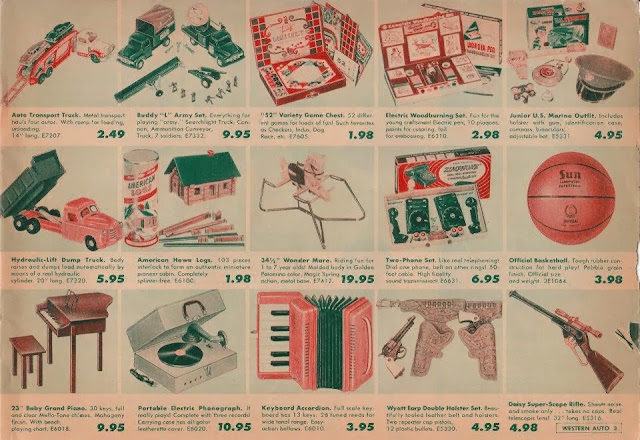

The extremely high-ceilinged store had a mezzanine level consisting of two open, balustraded wings that extended along both sides of the front half of the long rectangular building. A set of center stairs provided access. We put riding toys on one side of the mezzanine and small items on the other—dolls, dollhouses, toy cars and trucks, tin service station sets, wind-up toys, cowboy pistol sets, board games, toy soldiers, push and pull toys for toddlers, and more. Sometimes little kids would try out the tricycles and pedal cars by riding them up and down the aisle.

Along about Thanksgiving, or shortly after, my father sometimes hired a part-time clerk, and we decorated one or both front display windows with lights, toys, sports items, and small appliances such as toasters, mixers, and portable radios. The store had all sorts of other potential gift items, too, ranging from hunting and fishing materials to tools and automobile accessories. We also sold Trutone radios and TVs and Wizard appliances.

Along about Thanksgiving, or shortly after, my father sometimes hired a part-time clerk, and we decorated one or both front display windows with lights, toys, sports items, and small appliances such as toasters, mixers, and portable radios. The store had all sorts of other potential gift items, too, ranging from hunting and fishing materials to tools and automobile accessories. We also sold Trutone radios and TVs and Wizard appliances.

In addition to being a major local source for Santa Claus, we were also one of the principal retail locations for fireworks—sparklers, firecrackers of various sizes, handheld roman candles, skyrockets mounted on slender sticks so that soft drink bottles could be used for launch pads, cherry bombs, and others. Most of that stuff came from China and was packaged in thin red, yellow, and green tissue with glued-on labels in English and Chinese. Very exotic and appealing. We displayed them on tables near the front door, starting a couple of weeks before Christmas. Over time, we came to know which customers would buy which items.

These were years when small-town merchants often sold things on credit and layaway. Parents and grandparents would buy things weeks before Christmas and leave the items to be paid off and picked up later. We wrapped them all in the same thick Christmas paper (no ribbon and bows), put the buyers’ names on them, and stored them on a second-floor landing, out of traffic but visible from the stairs and mezzanine wings. It was fun to see the piles grow as Christmas drew closer. Everyone’s packages looked similar, but I don’t recall ever getting any mixed up and into the wrong hands, though we may have done so, and I’ve just suppressed that memory.

These were years when small-town merchants often sold things on credit and layaway. Parents and grandparents would buy things weeks before Christmas and leave the items to be paid off and picked up later. We wrapped them all in the same thick Christmas paper (no ribbon and bows), put the buyers’ names on them, and stored them on a second-floor landing, out of traffic but visible from the stairs and mezzanine wings. It was fun to see the piles grow as Christmas drew closer. Everyone’s packages looked similar, but I don’t recall ever getting any mixed up and into the wrong hands, though we may have done so, and I’ve just suppressed that memory.

Kids would often show parents what they wanted Santa to bring. Even as a ten-or-twelve-year-old, I could tell that some kids wanted things their parents could not afford, and it always made me sad. It still does.

Other stores along Main Street—a variety store that also had some smaller toys as well as children’s books, three clothing stores, a jeweler, a drugstore, a floral shop, and a hardware store among them—made their own merchandising preparations and put out decorations. And the town hung strings of red, yellow, green, and blue lights over the wide street from one side to the other. We all thought they were gorgeous, and they made us feel like we lived in a big city somewhere.

Well before any of that, however, the annual Sears, Roebuck and Company Christmas catalog would arrive. I have no idea how many copies flowed though our town’s little post office along with all the Holiday cards going out and coming in. But I’m confident that my brother and I were not the only children who poured over that magnificent wish book page by page, time and again. I remember drooling not only over toys but also over watches and sporting goods of all kinds.

A couple of weeks before Christmas, my father would put lights around our modest front porch and mount a lighted cross or star, and sometimes both, on the roof. One year he cut a two-dimensional Santa and chimney out of plywood, painted them appropriately, and put them on the roof. Other families put up lights, too, and lots of folks would drive around the small town at least once to look at them. Later, they would ask others if they had seen so-and-so’s house.

A couple of weeks before Christmas, my father would put lights around our modest front porch and mount a lighted cross or star, and sometimes both, on the roof. One year he cut a two-dimensional Santa and chimney out of plywood, painted them appropriately, and put them on the roof. Other families put up lights, too, and lots of folks would drive around the small town at least once to look at them. Later, they would ask others if they had seen so-and-so’s house.

Then came the annual search for the perfect cedar tree—there were no fir or spruce trees where we lived, or any imported for sale that I recall. Pine was the only other choice, and my father would not have one of those. He kept an eye out for right-sized cedar trees all year long, but when it came time to cut one, it seemed like completing the search took forever before he would settle on one to cut.

After that came the tree decorating itself, with colored lights, glass ornaments, some plastic ones, occasionally a few strings of shiny garland, and last, but not least, tinsel icicles, all of which had to be applied just right, one at a time. We also sold tree decorations in the store.

After that came the tree decorating itself, with colored lights, glass ornaments, some plastic ones, occasionally a few strings of shiny garland, and last, but not least, tinsel icicles, all of which had to be applied just right, one at a time. We also sold tree decorations in the store.

Finally, school would let out for a whole week, shopping at the store would pick up, we would stay open late, and the town would be abuzz evenings under those magnificent lights over Main Street. Some churches would have special services with congregational singing, choir specials, and kids’ pageants. I have a vague recollection of carolers going around town too. There would also be collections taken for those less fortunate in the community.

My paternal grandmother lived with us and had her own apartment on one side of our house (she lived in three rooms, and we lived in four). Every year she would unpack her small, folding, pre-WWII-era artificial tree, and my brother and I would help her decorate it. Then, one evening shortly before Christmas, her other four grown children and their families would assemble at our house to eat, catch up on family news, tell stories, and exchange gifts. For some reason, I have clearer memories of those gatherings than I do of Christmas morning with just Gran and our immediate family.

Eventually, Christmas Eve would roll around, and adults who had bought items on layaway would come to the store, usually after their children’s bedtime, to pick up their purchases. It was a fun experience for all of us. With one exception. We had this one neighbor with three kids a little younger than my brother and me, and he bought generously from us but was always the last one to come for his purchases. We would sit anxiously waiting for him so we could go close the store and go home, and more than once we had to call to remind him.

Eventually, Christmas Eve would roll around, and adults who had bought items on layaway would come to the store, usually after their children’s bedtime, to pick up their purchases. It was a fun experience for all of us. With one exception. We had this one neighbor with three kids a little younger than my brother and me, and he bought generously from us but was always the last one to come for his purchases. We would sit anxiously waiting for him so we could go close the store and go home, and more than once we had to call to remind him.

This was the most exciting night of the year for going to bed, but the hardest for getting to sleep, whether we still believed in Santa Claus or not. I recall the year some kid at school told me the truth about the jolly old elf and how disappointed my parents were when I told them what had happened. A few years later, when my brother was beginning to catch on, I made up a story about Santa’s helpers leaving notes written in code around the house warning him to believe or risk not getting any presents. I wrote the notes backwards, and my brother had to hold them up to a mirror to read them. The ruse worked almost until Christmas before he caught on.

And then, of course, there was Christmas morning and presents. At the time, I never thought about how many other kids were opening presents bought at the Western Auto store, but there must have been a lot. After all the Santa doings and a little bit of play with our gifts, we would rush outside while it was still dark—we got up early despite getting to bed late—and shoot fireworks. That ensured that everyone else in the neighborhood also awoke early, whether Santa had visited them or not. This was a pattern repeated all around town.

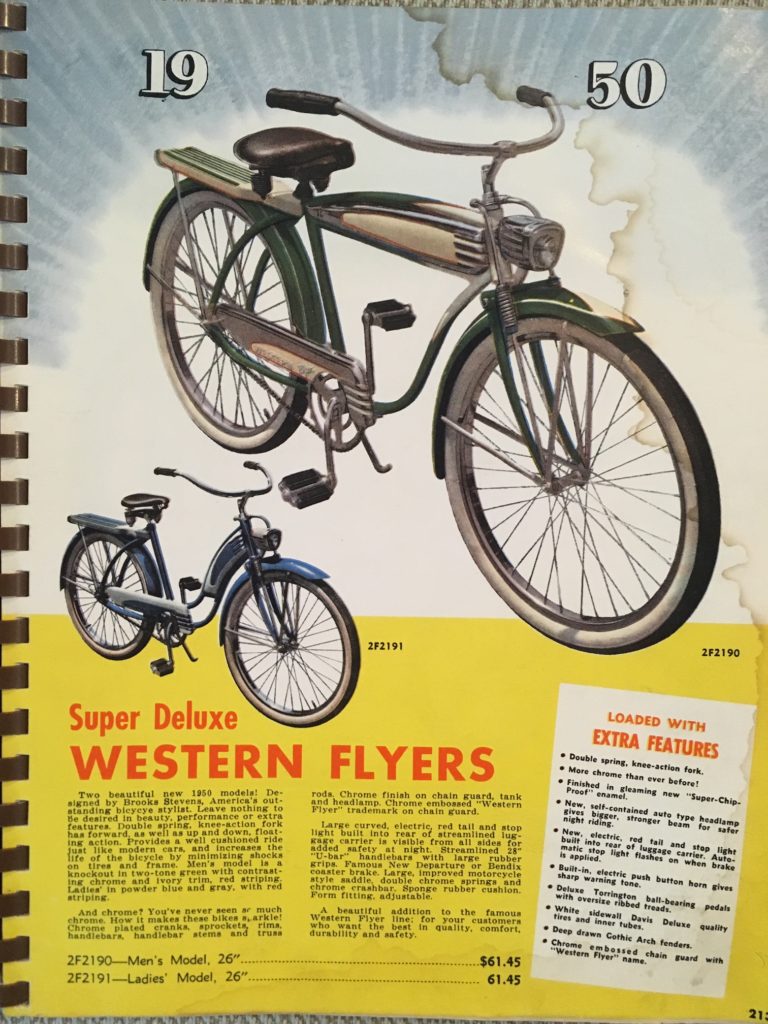

Strangely, I remember all the preparations for Christmas more vividly than Christmas mornings. I think that’s because the anticipation was as much fun as the reality, and it went on longer. I still remember the best physical Christmas gift I ever received, however. It was the one-and-only new bicycle I ever owned. It was too big for me at the time, but I learned to cope quickly. It was a 26-inch 1950 Western Flyer with white sidewall tires, front and rear lights, front shocks, and a horn. A vintage 1949 Western Auto catalog featuring the bike sits on a table in my office to this day.

Strangely, I remember all the preparations for Christmas more vividly than Christmas mornings. I think that’s because the anticipation was as much fun as the reality, and it went on longer. I still remember the best physical Christmas gift I ever received, however. It was the one-and-only new bicycle I ever owned. It was too big for me at the time, but I learned to cope quickly. It was a 26-inch 1950 Western Flyer with white sidewall tires, front and rear lights, front shocks, and a horn. A vintage 1949 Western Auto catalog featuring the bike sits on a table in my office to this day.

Maybe, though, the best gift of all was the people who were all around me that whole time—family uppermost of course, but also friends, store customers, and townsfolk in general—who in making their own memories were helping me make ones to savor for the rest of my life.

Our family was not well-to-do, or even close to it. Because of the store and because my mother was a teacher bringing in a second income, we were better off than some families in our community, but less so than some others. I thought friends and classmates probably believed my brother and I could have anything we wanted from the store, but that was not the case. However, we were wealthy in some immeasurable ways—chief among them the respect our parents enjoyed in the community, the wider views their professions provided us of small-town life, the love that filled our home, and the memories we were making—all of them things time cannot take away. A person can’t ask for better gifts, especially at Christmas.

A note about Western Auto: The company was founded in 1909 in Kansas City as an auto parts mail-order house and over time evolved into a company similar to Sears, Roebuck and Company but without clothing and such. At its peak in the 1960s, Western Auto had about 1,500 company-owned stores nationwide and about 4,000 “Associate” stores. Associate stores could operate under the Western Auto brand and advertising to sell Western Auto products, but they could also sell other things. My father sold hardware and building supplies in his Associate store. Sears bought Western Auto in the 1980s and sold it shortly afterward. Eventually, Advance Auto Parts bought the company and eliminated the brand.

A note about the illustrations: The toy ads are from a 1956 Western Auto Christmas Catalog. The bicycle ad is from the 1949 Western Auto Fall Catalog. The Christmas tree photo and the house photos are from the early 1960s. The 1929 Model-A Ford in the driveway was a personal “fix-it-up” project during my college years.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.