What year in America does the following describe, 2022 or 1922? Loved ones gone in a pandemic; racial violence plaguing towns and cities; veterans home from war but still suffering the effects of battle; careless exploitation of natural resources ravaging the environment; infrastructure failing to meet current needs; cultural division over fear of foreigners and non-Protestant religions; fear of socialism; drugs being smuggled across the Mexican border and through American ports. The answer is both.

These are only some of the similarities between 2022 and 1922, the year I have been living in for the last twelve months and more. By coincidence, a novel I had been holding in the back of my mind for more than a decade and working on almost daily during 2021 is slated for publication this fall, during the one hundredth anniversary of the time in which it is set. That is, assuming pre-publication readers do not identify insurmountable problems with the first draft, completed this past week.

These are only some of the similarities between 2022 and 1922, the year I have been living in for the last twelve months and more. By coincidence, a novel I had been holding in the back of my mind for more than a decade and working on almost daily during 2021 is slated for publication this fall, during the one hundredth anniversary of the time in which it is set. That is, assuming pre-publication readers do not identify insurmountable problems with the first draft, completed this past week.

The novel is as at heart a story of love struggling against hate and revenge, but it takes place amid, and is shaped by, the cultural, financial, political, and environmental issues of the time. As a historian, I was familiar with those before I started. Nevertheless, as I worked on the novel I kept thinking anew about how remarkable it is that Americans are still dealing with the same types of issues that troubled us one hundred years ago. Perhaps “remarkable” is not the right word. Maybe “frightening” is more accurate.

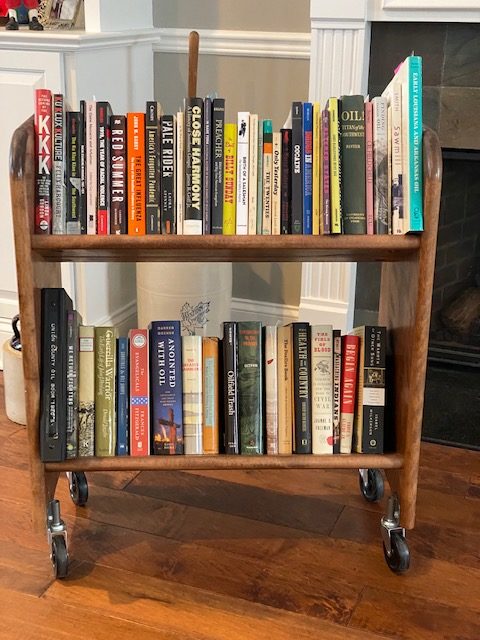

There are numerous ways to go about creating a novel. For example, some novelists outline; some do not. Some novelists do extensive research; some do not. Some novelists polish as they go; others create several drafts and rewrites. I fall into the outline, research, and polish as I go categories—emphasis heavy on research piece. Perhaps “overboard” is more accurate than “heavy emphasis” when it comes to describing time invested. But it’s a fun part of the process.

There are numerous ways to go about creating a novel. For example, some novelists outline; some do not. Some novelists do extensive research; some do not. Some novelists polish as they go; others create several drafts and rewrites. I fall into the outline, research, and polish as I go categories—emphasis heavy on research piece. Perhaps “overboard” is more accurate than “heavy emphasis” when it comes to describing time invested. But it’s a fun part of the process.

To some degree, the genesis for this novel dates to the early 1970s when an aunt in Southern Arkansas started sending me “Found in Old Newspapers” clippings from the El Dorado Daily News about the oil boom that occurred there in the 1920s. I had no plans to write about it, but I read the clippings and held onto them.

In the late 1970s, a group of folks began looking into creating a museum about the boom and subsequent development of a petroleum-based economy there in Union County and neighboring areas. At the time, I worked for the American Association for State and Local History in Nashville, Tennessee, and thought that if the museum plans went anywhere, it might be interesting to apply for the position of director and, if successful, consider moving back to Arkansas. So, I did a lot of reading about the entire period of early oil exploration in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas, all rich in Gulf Coast Plain deposits. The museum did not get off the ground at the time, and I realized later that the position would not have been a good fit for me anyway, nor nearly as good as other opportunities that came along.

In the late 1970s, a group of folks began looking into creating a museum about the boom and subsequent development of a petroleum-based economy there in Union County and neighboring areas. At the time, I worked for the American Association for State and Local History in Nashville, Tennessee, and thought that if the museum plans went anywhere, it might be interesting to apply for the position of director and, if successful, consider moving back to Arkansas. So, I did a lot of reading about the entire period of early oil exploration in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas, all rich in Gulf Coast Plain deposits. The museum did not get off the ground at the time, and I realized later that the position would not have been a good fit for me anyway, nor nearly as good as other opportunities that came along.

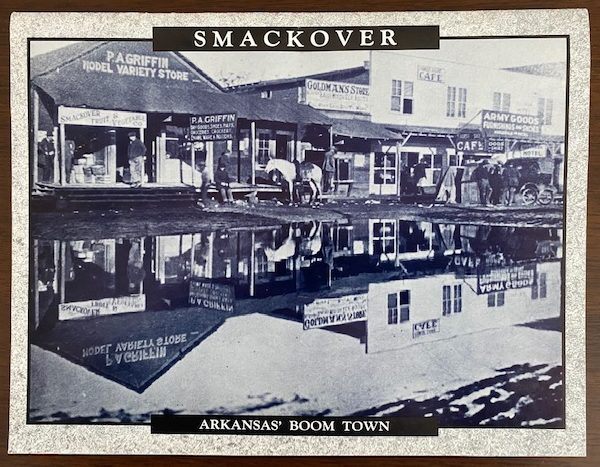

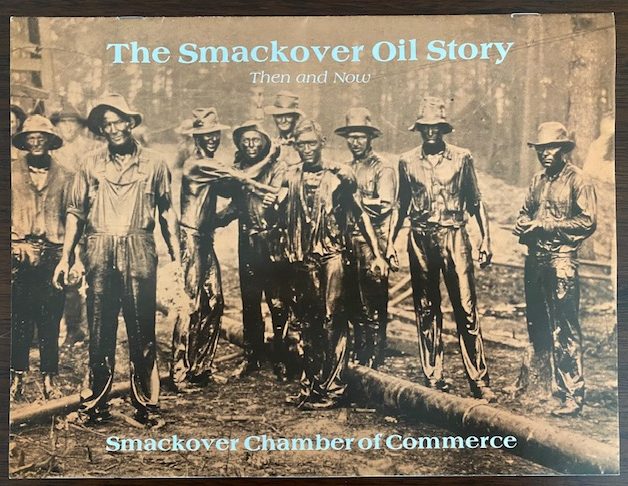

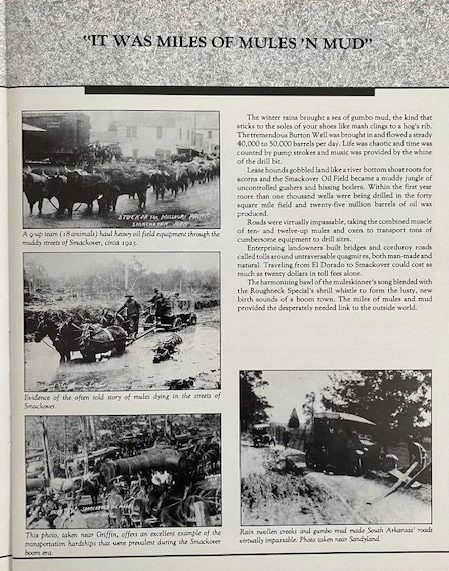

Things have a way of coming full circle, though, and eventually the state established the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in tiny Smackover, on the northern edge of Union County. The museum had quite a story to tell, not only about the technical aspects of oil exploration and production, and the long-lasting economic development of the area. But also about population growth. Smackover had about one hundred inhabitants when oil was discovered there in mid-1922, and by the end of the year, the population had swelled to more than 20,000. A year before, the county seat of El Dorado had experienced its own boom period and seen its population go from about 4,000 to some 40,000.

Depending on one’s point of view, the rapid growth either brought chaos masquerading as progress or progress sheathed in chaos. At the time, Union County oil production ranked at the top in the nation, making news on Wall Street and across the South, Midwest, and West.

Depending on one’s point of view, the rapid growth either brought chaos masquerading as progress or progress sheathed in chaos. At the time, Union County oil production ranked at the top in the nation, making news on Wall Street and across the South, Midwest, and West.

With the oil came soon-to-be-millionaire businessmen (H. L. Hunt among them), oil field workers, tradesmen of all kinds, and merchants to serve them. There came also lease hounds, creekologists selling fake oil-finding services, cardsharps, moonshiners, bootleggers (it was the age of prohibition), drug smugglers, prostitutes, and more. And, oh yes, the Ku Klux Klan.

The race to get the black gold out of the ground led to all sorts of waste (half of the deposits are still there because of drilling practices at the time), polluted streams, denuded forests, and impenetrable oil crusts on thousands of acres of farmland.

I knew as soon as I completed my first novel that I had to write one set during the oil boom, and now, thanks to living the past year in 1922, I have. It’s my third. My 1922 “homeplace” included an array of books not only about oil and oil booms but books about the 1920s in general and about specific topics such as mules, sawmills, the famous revivalist Billy Sunday, African-Americans in WWI, the Klan, the Spanish flu pandemic, prohibition, and drugs.

In addition to all the newspaper clippings my aunt had sent me years earlier, I had the Internet, too, of course. But the single most valuable source was oral history interviews that in the 1980s, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources collected from nearly 450 people who had lived in Union County through the boom era. Many of the types of experiences they shared with the museum found their way into the novel.

In addition to all the newspaper clippings my aunt had sent me years earlier, I had the Internet, too, of course. But the single most valuable source was oral history interviews that in the 1980s, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources collected from nearly 450 people who had lived in Union County through the boom era. Many of the types of experiences they shared with the museum found their way into the novel.

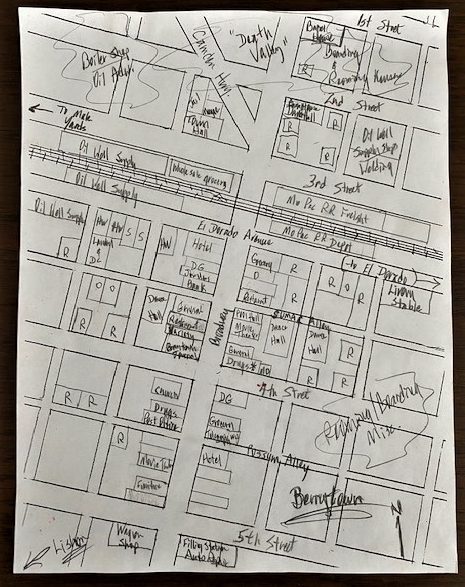

One of the things I enjoyed about this novel was creating an imaginary town inspired by the real town of Smackover. My imaginary town, named “Berrytown,” had to be similar but also different, and to ensure that, I had not only to imagine it but sketch a crude map of it. I used it often but deviated from it where desirable in the story.

The novel, currently untitled (Back to the Future is taken), features a single WWI veteran from Indiana with a score to settle, a local widow of the US Army’s 1916 Pancho Villa expedition, her twelve-year-old son, an aging white farmer not happy with all the commotion and pollution, that farmer’s black neighbor who is also a preacher, and a cast of secondary characters representing most of the various types of people who lived in or migrated to the area.

The novel, currently untitled (Back to the Future is taken), features a single WWI veteran from Indiana with a score to settle, a local widow of the US Army’s 1916 Pancho Villa expedition, her twelve-year-old son, an aging white farmer not happy with all the commotion and pollution, that farmer’s black neighbor who is also a preacher, and a cast of secondary characters representing most of the various types of people who lived in or migrated to the area.

My hope is that, as with my novel South of Little Rock, readers will laugh, cry, get mad, and find rays of hope. Plus, find interesting and informative parallels between today and a hundred years ago, especially as they relate to environmental issues.

To be notified of new posts, please email me via the Contact page.